Liver Transplantation: Eligibility, Surgery, and Immunosuppression Explained

When your liver fails, there’s no backup. No reset button. No pill that can rebuild it. For people with end-stage liver disease, a liver transplant isn’t just an option-it’s the only chance to survive. But getting one isn’t as simple as signing up. It’s a long, strict, and deeply personal journey that involves medical evaluations, surgical risk, and a lifetime of medication. Here’s what really happens-from who qualifies, to what the surgery looks like, to how your body learns to accept a new organ.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

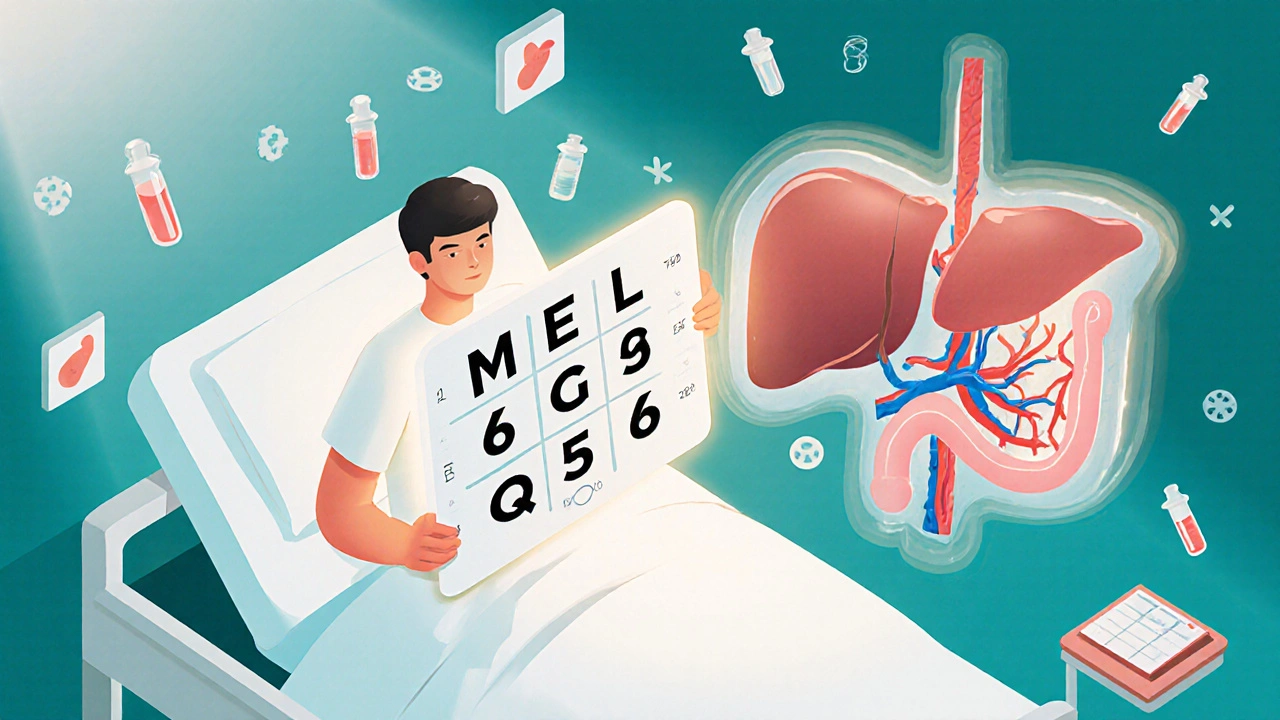

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The system is designed to give organs to those who need them most and have the best chance to survive. The key tool used to decide this is the MELD score-Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. It’s calculated using three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The score runs from 6 to 40. Higher numbers mean you’re sicker. Someone with a MELD of 35 is in critical condition and will jump ahead of someone with a MELD of 15. But the score isn’t the whole story. If you have liver cancer, you must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors each under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level is above 1000 and doesn’t drop below 500 after treatment, you’re usually not eligible unless your case gets special review. Then there’s the lifestyle part. Active alcohol or drug use is an automatic disqualifier. Most centers require at least six months of sobriety before listing. But here’s the catch: some centers are starting to question this rule. A 2023 study from Yale found that patients with just three months of abstinence had nearly the same five-year survival rates as those who waited six months. Still, many programs stick to the six-month rule because they need to be sure you won’t go back to drinking after the transplant. Psychosocial factors matter too. You need stable housing, a support system-someone to drive you to appointments, help you take pills, notice if you’re getting sick-and the mental health to handle the stress. Social workers, psychiatrists, and addiction specialists all weigh in. If you’re homeless, struggling with depression, or have no one to help you, you might be delayed-even if your liver is failing. Living donors add another layer. Donors must be between 18 and 55, have a BMI under 30, and be in perfect health. No smoking, no drinking, no history of liver, heart, or kidney disease. They need to have enough liver left after donation-at least 35%-and the donated piece must be big enough for the recipient-usually at least 0.8% of the recipient’s body weight. Some centers are now considering donors up to BMI 32 or even 35, especially if they have exceptional liver quality.What Happens During the Surgery?

A liver transplant isn’t a quick operation. It takes between six and twelve hours. The surgeon removes your damaged liver, waits for the new one to arrive, and then connects the blood vessels and bile ducts. Most surgeries use the “piggyback” technique-keeping your inferior vena cava (a major vein) in place-because it reduces bleeding and makes the procedure safer. About 85% of transplants use this method. The surgery has three phases. First, the hepatectomy: removing your liver. Then, the anhepatic phase: you have no liver. Your body survives on temporary support systems. Finally, implantation: the new liver is stitched in. Blood flow is restored. Bile starts flowing. If everything goes right, you’re alive with a new organ. For living donor transplants, surgeons remove 55% to 70% of the donor’s right lobe. For children, they take the left lateral segment. The donor’s liver regrows to nearly full size in about six to eight weeks. The recipient’s new liver also regrows, but faster-often within weeks. Donor liver sources matter too. Most come from deceased donors who died from brain death. But in 12% of cases, organs come from donors after circulatory death (DCD)-people whose hearts stopped and couldn’t be restarted. These livers have a higher risk of bile duct problems-about 25% versus 15% for brain-dead donors. But new tech is helping. At the University of Pittsburgh, they use machine perfusion to keep DCD livers alive outside the body. This has cut bile complications down to 18%. Geography plays a big role. If you live in California (Region 9), you might wait 18 months for a liver with a MELD score of 25-30. In the Midwest (Region 2), you might wait only 8 months. The system tries to be fair, but organs don’t move easily across state lines. That’s why some people travel to transplant centers with shorter wait times.

Comments (8)

Rodney Keats

14 Nov 2025

So let me get this straight-I can’t drink for six months to get a new liver, but if I’m rich enough to live in the right zip code, I get one faster? And the guy who’s been sober for three months but lives in Mississippi is just out of luck? Cool. Real cool. The system’s not broken-it’s a fucking game of Monopoly with organs as properties.

Laura-Jade Vaughan

15 Nov 2025

OMG this post is SOOOOO insightful 💖 I literally cried reading about the piggyback technique 🥹 The fact that they’re using machine perfusion now?? 🤯 It’s like sci-fi but REAL. And the part about steroid-sparing protocols?? That’s the future right there. I’m already planning my donor party-pink balloons, glitter, and a playlist of ‘Eye of the Tiger’ 😘

Jennifer Stephenson

16 Nov 2025

Transplants save lives. The rules are strict for a reason. Recovery is hard. Medications are expensive. But people do it. Every day.

Segun Kareem

17 Nov 2025

This isn’t just medicine-it’s a testament to human resilience. Every organ donated is a whisper from the dead saying, ‘Keep going.’ Every patient who takes their pills, shows up for checkups, and breathes another day? That’s a victory. Not just medical. Spiritual. We forget that. The liver doesn’t just heal the body-it reminds us we’re still here, still fighting. And that’s worth more than any score, any waitlist, any dollar.

Philip Rindom

18 Nov 2025

Wow, I didn’t realize DCD livers had such high bile duct risks. But that perfusion tech at Pittsburgh? Genius. Also, the 3-month sobriety study is wild-makes you wonder if the six-month rule is more about fear than data. Still, I get why centers are cautious. One relapse after transplant… yikes. I’d want my doc to be extra careful too.

Jess Redfearn

19 Nov 2025

Wait, so if I’m overweight and have high blood pressure, I can’t be a donor? But I’m healthy otherwise? That’s dumb. My cousin donated a kidney and he’s fine. Why not just check the liver? Why make it so hard? Also, can I donate my liver to my dog? He’s got liver problems too.

Ashley B

19 Nov 2025

They’re lying. All of it. The MELD score? A cover-up. The real reason people get transplants is because they’re on the pharmaceutical payroll. The drugs? Made to keep you sick so you keep buying. And the ‘regeneration’? That’s just the liver pretending to heal so you don’t notice the nanobots they implanted during surgery. They’re testing mind control. You think you’re getting better? You’re being programmed. Wake up.

Sharon Campbell

21 Nov 2025

lol who even cares about this long post. i read the title and thought ‘oh cool’ but then i saw all the words. who has time for this? also why is everyone so obsessed with ‘immunosuppression’? just take the pill. its not that hard. also i think the liver just grows back on its own if you drink less. i heard that on tiktok.