Drug Take-Back Programs in Your Community: How They Work and Where to Find Them

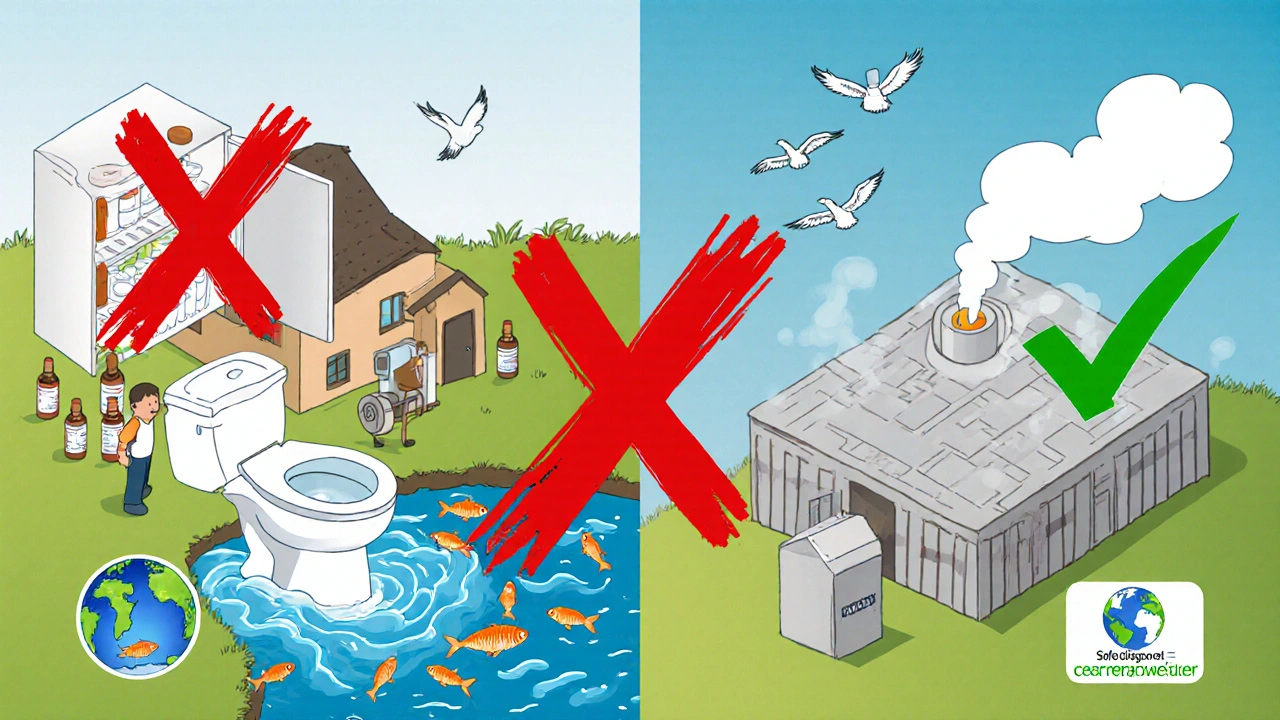

Every year, millions of unused or expired pills sit in bathroom cabinets, kitchen drawers, and medicine chests across the country. Many people don’t know what to do with them-so they flush them, toss them in the trash, or just leave them there. But here’s the truth: drug take-back programs are the safest, most responsible way to get rid of old medications. And they’re closer than you think.

What Exactly Are Drug Take-Back Programs?

Drug take-back programs are official, government-backed systems that let you drop off unwanted, expired, or unused medicines at secure locations. These programs exist to stop pills from ending up in water supplies, landfills, or the hands of kids, teens, or strangers who might misuse them. The idea isn’t new-it’s been around since 2010, when Congress passed the Secure and Responsible Drug Disposal Act. That law gave the DEA the power to set up permanent drop boxes and organize nationwide collection events.

Today, there are over 16,500 permanent drop-off locations across the U.S.-mostly in pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations. These aren’t one-day events. They’re open year-round. And they’re not just for prescriptions. You can drop off over-the-counter pills, vitamins, patches, ointments, and even pet medications.

What Can You Actually Drop Off?

Not everything goes in the box. The rules are clear, and they’re there for safety and environmental reasons.

- Accepted: Pills, tablets, capsules, liquid medicines in sealed containers, prescription patches (like fentanyl), ointments, vitamins, and pet meds.

- Not accepted: Inhalers (aerosols), needles, syringes, thermometers, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, iodine-based products, or illegal drugs.

If you’re unsure, check the container. If it’s a medicine you bought at a pharmacy, it’s probably fine. If it’s a cleaning product or a chemical, it’s not. Keep the meds in their original bottles if you can. If not, put them in a sealed plastic bag. The key? Remove or cover your name and address on the label-your privacy matters.

How Do These Programs Work?

There are three main ways to use a take-back program:

- Permanent drop boxes: These are locked, secure bins in pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations. You walk in, drop it in, and leave. No questions asked. Walgreens alone has over 1,600 of these boxes across 49 states. Since 2016, they’ve collected more than 2.4 million pounds of meds.

- Mail-back envelopes: Some pharmacies and states give you free, prepaid envelopes. You put your meds inside, seal it, and drop it in any mailbox. It’s convenient-but only 63% of rural areas offer this service, compared to 89% of cities.

- Biannual collection events: The DEA runs National Prescription Drug Take Back Day in April and October. In April 2025, nearly 4,600 sites collected over 620,000 pounds of medication. But these events are temporary. Permanent drop boxes are more effective long-term.

Once collected, the meds are shipped to special facilities and destroyed by high-temperature incineration. That’s the only method approved by the EPA and FDA because it prevents contamination of soil and water.

Why Do These Programs Matter?

It’s not just about cleaning out your cabinet. It’s about saving lives.

More than 100,000 Americans die each year from drug overdoses. A huge chunk of those involve prescription pills that were never properly disposed of. Teens often find them in their own homes. Studies show communities with permanent drop boxes see a 17% drop in accidental poisonings and prescription misuse. In places like Broward County, Florida, mobile collection units that visit schools and community centers boosted participation by 73%.

And it’s not just about addiction. Flushing pills pollutes rivers and lakes. The EPA says pharmaceutical waste in water is a growing environmental problem. Take-back programs keep those chemicals out of the ecosystem.

Where Can You Find a Drop-Off Location?

You don’t have to guess. The DEA has a simple, searchable map on their website: DEA.gov/takeback. Just enter your zip code, and it shows you every nearby drop box-pharmacies, hospitals, police stations-all with hours and addresses.

In cities, you’ll usually find one within a mile. In rural areas, it’s harder. That’s why some communities use mobile units. If you live in a small town, check with your local pharmacy or county health office. Some even offer free mail-back kits.

And if you’re in the military or a veteran: the Military Health System runs its own take-back program. You can drop off meds at military hospitals or clinics year-round.

What If There’s No Drop-Off Near You?

If you’re stuck-no pharmacy, no police station, no mail-back option-the FDA has backup instructions. But only use these as a last resort.

Here’s what to do:

- Take pills out of their original bottles.

- Crush tablets or open capsules.

- Mix them with something unappetizing-used coffee grounds, kitty litter, or dirt.

- Put the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or container.

- Throw it in the trash.

Don’t flush unless it’s one of the 15 specific drugs on the FDA’s flush list-mostly powerful opioids like fentanyl patches that can be deadly if someone finds them in the toilet. For everything else? Trash with mix-ins is safer than flushing.

Why Don’t More People Use These Programs?

Here’s the problem: awareness is low. Only 28% of Americans know there are year-round drop boxes. Most still think take-back day is the only option. And in some places, police-run drop boxes scare people away. One study found participation dropped 32% when collection points were only at police stations.

Pharmacies are the answer. People trust pharmacists. They’re open longer hours. They’re in neighborhoods. And they don’t feel like law enforcement. Communities with pharmacy-based drop boxes see 41% higher participation than those with police-only sites.

There’s also a cost issue. Setting up a drop box costs $1,200 to $2,500 upfront. Many small towns can’t afford it. That’s why federal funding and partnerships with companies like Stericycle and Walgreens are so important.

What’s Changing in 2025?

Things are improving. The DEA’s “Every Day is Take Back Day” campaign has pushed the number of permanent locations up from 5,000 in 2020 to over 16,500 today. That’s a 210% increase in just seven years.

There’s also new legislation in the works. H.R. 4278, proposed in 2023, would require Medicare Part D plans to pay for mail-back envelopes. That could help 48 million seniors who can’t easily get to a drop box.

And some states are getting creative. Texas and California ran bilingual outreach campaigns for Hispanic communities-and saw participation jump 39%. Programs that speak people’s language work better.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for a national event. Here’s your quick action plan:

- Check your medicine cabinet. Pull out anything expired, unused, or no longer needed.

- Remove your name and address from the labels.

- Go to DEA.gov/takeback. Find the nearest drop box.

- Drop it off. That’s it.

And if you have family or friends who might not know about these programs? Tell them. Share the link. Help them find a drop box. One conversation could prevent a tragedy.

Medications aren’t trash. But they’re not meant to be kept forever either. Take-back programs give them a safe, final stop. And that’s something worth doing.

Can I drop off my old insulin pens or needles in a take-back box?

No. Needles, syringes, and sharps are not accepted in drug take-back boxes. These require special medical waste disposal. Many pharmacies and hospitals have separate sharps disposal containers. Check with your local pharmacy or health department for options. Some communities offer mail-back sharps containers as well.

Are drug take-back programs free to use?

Yes. All DEA-approved drop boxes and mail-back programs are completely free. You never pay to dispose of medications through these programs. If someone asks for money, it’s not an official take-back site. Report it to the DEA.

What if I live in a rural area with no drop box nearby?

Check with your local pharmacy or county health office-they may offer mail-back envelopes or host mobile collection events. Some states send free kits by mail. If nothing’s available, follow the FDA’s at-home disposal method: crush pills, mix with coffee grounds or kitty litter, seal in a bag, and throw in the trash. Never flush unless it’s on the FDA’s flush list.

Can I drop off medications for someone else?

Absolutely. You can drop off medications belonging to family members, neighbors, or even pets. Just make sure personal information is removed from the labels. The program doesn’t track who drops off what-it’s anonymous and confidential.

Do drug take-back programs really make a difference?

Yes. Communities with permanent drop boxes report a 19% drop in teen prescription drug misuse within three years. The DEA has collected nearly 20 million pounds of medication since 2010. That’s 20 million doses that didn’t end up in a child’s medicine cabinet, a landfill, or a river. It’s not just about cleaning up-it’s about preventing addiction and overdose before it starts.

Next Steps: What to Do Now

If you’ve been holding onto old meds, don’t wait. Take five minutes today and check DEA.gov/takeback. Find your nearest drop box. Gather your expired pills. Drop them off. It’s simple. It’s safe. And it’s one of the most responsible things you can do for your family and your community.

And if you’re a pharmacist, a community leader, or just someone who cares-ask your local pharmacy to install a drop box. Push for mobile collections in underserved areas. This isn’t just a government program. It’s a community effort. And every pill that gets collected is one less danger in the world.

Comments (5)

Diana Askew

29 Nov 2025

They’re watching us. Every pill you drop in that box? Tracked. Linked to your name. Your zip code. Your medical history. They say it’s anonymous, but come on-why do they need all that data? Next thing you know, they’ll charge you for ‘safe disposal fees’ or deny you insurance because you had too many painkillers. I’m not dropping anything. Let ‘em burn in the trash like the rest of us. 😒

King Property

30 Nov 2025

Wow. Someone actually wrote a 2,000-word essay on how to throw away pills. Congrats. You just won the ‘Most Overexplained Thing Since Microwave Instructions’ award. The DEA map exists. You type your zip code. You find a Walgreens. You drop it in. Done. No need for the whole ‘FDA flush list’ lecture. I’ve got a 10-year-old son who knows more about this than you do. Stop writing novels. Just do it.

Yash Hemrajani

1 Dec 2025

Oh wow, a U.S.-centric guide with zero mention of how the rest of the world handles this. In India, we’ve had community pharmacy take-backs since 2018-and no one’s flushing anything. Why? Because we’re not rich enough to pretend we can afford federal programs. We just… don’t hoard. We use what we need, then throw the rest in the trash with ash. No boxes. No envelopes. No DEA. Just common sense. Maybe your problem isn’t disposal-it’s overprescribing. 🙄

Pawittar Singh

2 Dec 2025

Hey everyone-just wanted to say this is such a good reminder. 💪 I used to keep every pill I ever got, just in case. Then my cousin’s kid found a bottle of oxy in the bathroom cabinet. Scared the hell out of me. So I went to my local CVS, dropped off 17 bottles, and felt like a hero. 🙌 Seriously, if you’re reading this and you’ve got old meds? Do it. It’s free. It’s easy. And you’re not just cleaning your cabinet-you’re protecting someone’s life. Even if it’s just one. One less pill out there = one less tragedy. Let’s keep this going. Share this with your neighbors. Tag your local pharmacy. We got this. ❤️

Josh Evans

2 Dec 2025

Just dropped off my grandma’s stash at the Walgreens down the street. Took 2 minutes. No questions. No lines. The guy behind the counter even said thanks. Feels good to do the right thing. Thanks for the heads-up on the DEA map-had no idea it was this easy.