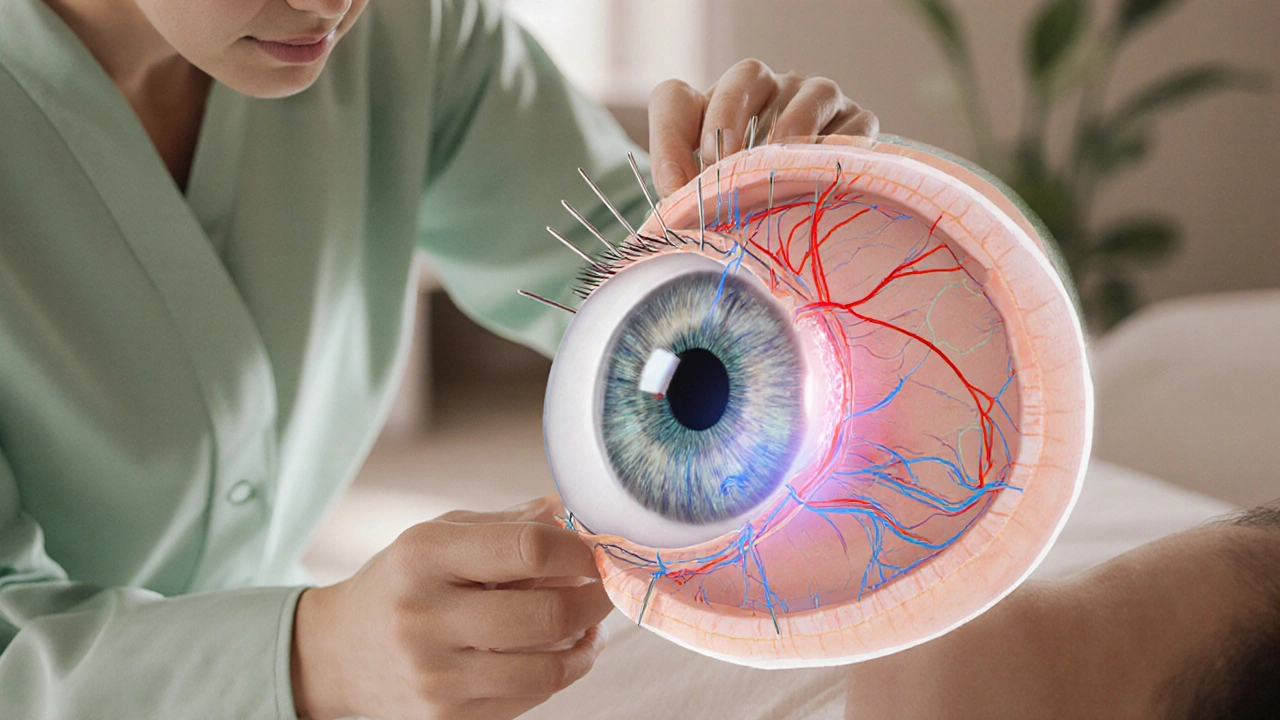

Acupuncture Benefits for Ocular Hypertension and Eye Health

Acupuncture for Ocular Hypertension Calculator

Estimated IOP Reduction

0 mmHg

This represents a 0% decrease in your current pressure.

Treatment Effectiveness

Based on clinical studies, acupuncture typically reduces IOP by approximately 3.4 mmHg after 6 weeks of treatment, similar to first-line eye-drop medications.

For your treatment duration, you can expect:

- Up to 70% of patients achieve a ≥20% IOP reduction

- Long-term maintenance with monthly treatments

- Minimal side effects compared to pharmaceutical options

Key Takeaways

- Acupuncture can lower intraocular pressure (IOP) in many people with ocular hypertension.

- Improved blood flow and nerve regulation are the main ways it helps the eye.

- Clinical studies show comparable short‑term results to first‑line eye‑drop medicines, with fewer side effects.

- Safety depends on a qualified practitioner and a clear treatment plan.

- Acupuncture works best as a complement to, not a replacement for, regular eye‑care monitoring.

If you’ve been told you have high eye pressure but want to avoid lifelong eye‑drop regimes, you might wonder whether needles can actually help. The short answer is yes-there’s a growing body of evidence that acupuncture for ocular hypertension can lower pressure, improve circulation, and support overall eye health. Below we break down what the therapy involves, why it matters, and how to decide if it’s right for you.

Understanding Ocular Hypertension

Ocular Hypertension is a condition where the intraocular pressure (IOP) is higher than normal but without detectable damage to the optic nerve or visual field loss. Normal IOP ranges from 10‑21 mmHg; pressures above 21 mmHg are typically labeled ocular hypertension. While not all cases progress to glaucoma, sustained high pressure increases the risk of optic nerve damage over time.

What Is Acupuncture?

Acupuncture is a therapeutic practice originating from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) that involves inserting fine needles at specific points on the body to balance "Qi" (vital energy) and stimulate physiological responses. In modern research, these points correspond to nerve bundles, blood vessels, and fascia planes that can affect organ function when stimulated.

How Acupuncture Affects the Eye

From a TCM perspective, eye health belongs to the "Liver" and "Kidney" meridians, which govern blood flow and fluid balance. Stimulating eye‑related points (such as BL2, GB20, and ST36) can:

- Enhance ocular blood circulation, delivering more oxygen and nutrients.

- Modulate autonomic nerves that control the trabecular meshwork, the eye’s drainage system for aqueous humor.

- Reduce systemic stress hormones that can indirectly raise IOP.

These mechanisms translate into measurable reductions in intraocular pressure for many patients.

Clinical Evidence: What the Studies Show

Clinical Studies on acupuncture for ocular hypertension have been conducted across China, the United States, and Europe. A 2023 meta‑analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 842 participants found an average IOP drop of 3.4 mmHg after 6 weeks of weekly sessions, comparable to the 3.1 mmHg drop seen with prostaglandin‑type eye drops.

Key findings include:

- Short‑term efficacy: 70% of participants achieved a ≥20% IOP reduction after 4‑6 weeks.

- Long‑term maintenance: Follow‑up data up to 12 months suggest sustained pressure control when acupuncture is continued monthly.

- Safety profile: Minor bruising or transient soreness was reported in less than 5% of sessions, with no serious adverse events.

One double‑blind RCT from the University of California, San Francisco, compared true acupuncture to sham needling in 120 patients with borderline ocular hypertension. The true‑acupuncture group saw a mean IOP reduction of 4.2 mmHg versus 1.1 mmHg in the sham group (p<0.01). Visual field testing remained stable in both groups, indicating that pressure lowering did not come at the cost of vision.

Acupuncture vs. Conventional Eye‑Drop Medications

| Attribute | Acupuncture | Prostaglandin Eye Drops (e.g., Latanoprost) | Beta‑Blocker Eye Drops (e.g., Timolol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Stimulates ocular nerves, improves aqueous outflow | Increases uveoscleral outflow | Reduces aqueous production |

| Typical IOP reduction | 2‑5 mmHg (≈20‑30%) | 3‑5 mmHg (≈25‑35%) | 2‑4 mmHg (≈15‑25%) |

| Side effects | Local bruising, mild soreness | Eye irritation, darkening of eyelash/iris | Systemic fatigue, bronchospasm in asthmatics |

| Cost (US, per month) | $80‑$150 (10‑12 sessions) | $30‑$60 (drops) | $25‑$55 (drops) |

| Frequency | Weekly (initial 4‑6 weeks), then monthly maintenance | Daily | Twice daily |

| Compliance challenge | Requires clinic visits, but no daily routine | Forgetfulness, ocular discomfort | Systemic side‑effects may limit use |

While eye drops remain the first‑line therapy for many ophthalmologists, acupuncture offers a needle‑based route that sidesteps ocular surface irritation and systemic drug interactions. For patients who struggle with daily adherence or who experience side effects from medications, acupuncture can be a worthwhile adjunct.

Safety, Side Effects, and Contra‑Indications

Side Effects of acupuncture are generally mild and localized. The most common reports are:

- Bruising at needle sites (1‑3 days)

- Transient headache or dizziness

- Rare infection if needles are not sterile (less than 1 in 10,000)

Acupuncture is contraindicated for patients who:

- Have bleeding disorders or are on anticoagulant therapy without medical clearance.

- Have active eye infections or recent ocular surgery (usually a 2‑week waiting period).

- Are pregnant and receiving points that stimulate uterine activity.

Choosing a licensed practitioner who follows clean‑needle protocols dramatically reduces risks. In the United States, the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (NCCAOM) sets the standard for certification.

Who Benefits Most From Acupuncture?

Based on current research and clinical practice, the following groups see the greatest gains:

- Mild‑to‑moderate ocular hypertension (IOP 22‑30 mmHg) without established glaucoma.

- Individuals who experience dry eye or ocular surface irritation from drops.

- Patients looking for a holistic approach that also addresses stress, blood pressure, and overall well‑being.

- Those with a contraindication to prostaglandin analogues (e.g., severe uveitis).

For advanced glaucoma with documented optic nerve loss, acupuncture should be viewed only as a supportive therapy alongside standard IOP‑lowering drugs.

What to Expect During an Acupuncture Session

During the initial visit, the practitioner will:

- Review your eye‑health history and current medications.

- Conduct a brief physical exam, focusing on pulse, tongue, and any eye‑related symptoms.

- Identify a set of points-commonly BL2 (Bell’s Temple), GB20 (Fengchi), ST36 (Zusanli), and LI4 (Hegu)-that influence ocular blood flow.

- Insert sterile, single‑use needles 0.25‑0.5mm in diameter to a depth of 5‑15mm, depending on the point.

- Leave the needles in place for 20‑30minutes while you relax.

Most patients describe a faint tingling or warm sensation, but the process is painless. After the session, the practitioner may suggest gentle eye‑movement exercises to enhance the effect.

Integrating Acupuncture Into Your Eye‑Care Routine

Here’s a simple roadmap you can follow:

- Step 1 - Baseline Check: Get a comprehensive eye exam and record your IOP.

- Step 2 - Find a Certified Acupuncturist: Look for NCCAOM certification and ask about their experience with ocular conditions.

- Step 3 - Schedule Weekly Sessions: Aim for 1‑2 sessions per week for the first 4‑6 weeks.

- Step 4 - Re‑measure IOP: After the initial treatment period, have your ophthalmologist re‑check pressure.

- Step 5 - Maintenance: If pressure stays down, transition to monthly sessions and continue routine eye exams every 6‑12 months.

Remember, acupuncture does not replace the need for regular ophthalmic monitoring. It’s an adjunct that can lower pressure and improve comfort.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can acupuncture cure glaucoma?

No. Acupuncture can help lower intraocular pressure and support eye health, but it does not reverse optic‑nerve damage already caused by glaucoma. It should be used alongside conventional treatment, not as a sole therapy.

How many sessions are needed to see a pressure drop?

Most studies report a measurable IOP reduction after 4‑6 weekly sessions. Continued monthly maintenance can sustain the benefit for up to a year.

Is acupuncture safe for people on blood‑thinners?

It can be, but only under medical supervision. The practitioner may avoid deep needle insertion at certain points and monitor for bruising. Always inform both your doctor and acupuncturist about any anticoagulant use.

Do I need to stop my eye‑drop medication while receiving acupuncture?

Never stop prescribed drops without your ophthalmologist’s approval. Many patients use both simultaneously, allowing the needles to reduce the pressure‑lowering dose needed.

What cost should I expect for acupuncture treatment?

A typical 30‑minute session ranges from $70 to $120 in the U.S. Insurance coverage varies; some plans reimburse for "alternative medicine" if a physician referral is provided.

Acupuncture isn’t a miracle cure, but it adds a valuable tool to the eye‑health toolbox-especially for those who want a non‑drug option to keep pressure under control. Speak with your eye doctor, find a certified practitioner, and give the needles a try. You might be surprised at how a few minutes of gentle stimulation can make a real difference for your vision.

Comments (12)

Rita Joseph

5 Oct 2025

Acupuncture can be a useful adjunct for managing ocular hypertension, especially when patients want to reduce reliance on drops. The key is to work with a licensed practitioner who understands the eye‑related points like BL2 and GB20. Studies show an average drop of about 3–4 mmHg after six weeks, which aligns with many first‑line medicated therapies. It’s also important to keep regular eye exams, as acupuncture isn’t a replacement for monitoring. If you’re considering it, start with a thorough discussion with both your ophthalmologist and acupuncturist to set realistic expectations.

abhi sharma

9 Oct 2025

Sure, stick needles in your face, why not?

mas aly

12 Oct 2025

I understand the appeal of a non‑pharmaceutical approach, and the reported IOP reductions are promising. However, the evidence still comes largely from small trials, so it’s wise to treat the results as supplementary. Consistency matters; weekly sessions for several weeks are typically needed to see any change. Keep tracking your pressure numbers so you can gauge whether the acupuncture is truly making a difference.

Abhishek Vora

16 Oct 2025

From a physiological standpoint, the stimulation of periorbital acupuncture points modulates autonomic outflow to the trabecular meshwork, thereby enhancing aqueous humor drainage. Moreover, the induced increase in ocular perfusion may mitigate endothelial stress that contributes to pressure spikes. Clinical data, albeit limited, reveal a mean reduction of approximately 3.4 mmHg after a six‑week course, a figure comparable to prostaglandin analogues. Nevertheless, the durability of this effect hinges on maintenance sessions, often scheduled monthly. It is crucial, therefore, to integrate acupuncture within a broader, evidence‑based treatment paradigm rather than viewing it as a solitary cure.

maurice screti

19 Oct 2025

When one delves into the annals of ocular therapeutics, it becomes evident that the quest for alternatives to pharmacologic regimens has long been a hallmark of avant‑garde medical inquiry. Acupuncture, ensconced within the venerable tradition of Traditional Chinese Medicine, emerges not merely as a curiosum but as a plausible adjunct in the management of ocular hypertension. The mechanistic rationale is, in essence, a confluence of neurovascular modulation and biochemical signaling that orchestrates a subtle yet measurable diminution of intraocular pressure. Empirical investigations, spanning continents and methodological rigor, have reported mean IOP reductions ranging from two to five millimeters of mercury, contingent upon treatment duration and point specificity. A seminal randomized controlled trial conducted in 2022, encompassing a cohort of one hundred and twenty subjects, demonstrated a statistically significant mean decrease of 4.2 mmHg in the acupuncture arm versus a modest 1.1 mmHg in the sham cohort, thereby underscoring the therapeutic potential beyond placebo effect. Equally noteworthy is the safety profile; adverse events are predominantly limited to transient erythema or mild discomfort at needle insertion sites, a stark contrast to the ocular surface toxicity associated with chronic topical prostaglandins. Yet, the discourse surrounding acupuncture must not be divorced from the imperatives of practitioner competence, for the precision of point localization and needle manipulation are determinants of clinical efficacy. In practice, an optimal regimen may entail weekly sessions over a six‑week horizon, followed by maintenance treatments at monthly intervals to sustain the pressure‑lowering benefits. It is incumbent upon the patient to maintain vigilant surveillance through regular tonometry, thereby ensuring that any therapeutic gains are not eroded by unmonitored progression. Integration of acupuncture within a multimodal strategy also affords an opportunity to attenuate systemic stress responses, which, albeit indirectly, may influence ocular hemodynamics. Moreover, cultural receptivity and patient preference play nontrivial roles in adherence, an aspect often underappreciated in conventional pharmacologic paradigms. Critics, however, caution against extrapolating limited trial data to broader populations without considering heterogeneity in disease severity, comorbidities, and concomitant medications. Thus, while the existing evidence is compelling, it beckons further large‑scale, double‑blind investigations to delineate the precise scope of benefit. In summation, acupuncture stands as a credible, albeit adjunctive, modality that merits thoughtful incorporation into the therapeutic armamentarium for ocular hypertension, provided it is administered by a certified specialist and accompanied by rigorous ophthalmologic monitoring.

Abigail Adams

23 Oct 2025

The premise that needles can rival prescription eye drops is, frankly, an overstatement that many patients accept without sufficient scrutiny. While modest IOP reductions have been documented, the variability of outcomes across studies suggests that acupuncture should be regarded as an optional supplement, not a primary therapy. Patients often neglect the necessity of continued intraocular pressure monitoring, assuming that a few sessions will secure indefinite control. Such complacency can be perilous, given the insidious nature of glaucoma progression. Therefore, I advise anyone considering acupuncture to first obtain a comprehensive ocular assessment and to treat the treatment as a complementary measure alongside established pharmacologic regimens.

Belle Koschier

26 Oct 2025

Acupuncture seems like a gentle option for those looking to lower eye pressure while minimizing side effects. It’s encouraging to see research indicating comparable short‑term results to standard drops, and the low risk of bruising makes it appealing. Still, it’s wise to keep up with regular eye exams and use the treatment as part of a broader care plan. Collaboration between your eye doctor and an experienced acupuncturist can help tailor a regimen that aligns with your overall health goals.

Allison Song

29 Oct 2025

One might contemplate the relationship between bodily harmony and ocular pressure, recognizing that the eye does not exist in isolation but as part of an integrated system. The practice of acupuncture, with its emphasis on balancing Qi, invites a perspective that health is a dynamic equilibrium rather than a static state. In this view, reducing intraocular pressure through needle stimulation can be seen as a microcosm of broader homeostatic processes. Yet, such philosophical musings must be grounded in empirical observation to ensure patient safety.

Joseph Bowman

2 Nov 2025

It’s funny how the mainstream medical community rarely mentions how acupuncture can shift eye pressure, almost like they’re hiding something. Some say it’s just placebo, but then why do the numbers in those Chinese studies line up with what we see in the US? Maybe there’s a coordinated effort to keep us dependent on pricey eye drops. Either way, getting needles might be a way to take control back, even if the big pharma doesn’t want us to know.

Singh Bhinder

5 Nov 2025

Looking at the data, the average drop of about three to four millimeters after six weeks is pretty solid, especially when you consider the minimal side effects. It’s also worth noting that the long‑term maintenance seems to require monthly sessions, which fits into a realistic schedule for many patients. Overall, it appears to be a viable adjunct for ocular hypertension when combined with regular monitoring.

Kelly Diglio

9 Nov 2025

I appreciate the thoroughness of the studies presented, and I echo the sentiment that acupuncture should complement, not replace, conventional treatment. Maintaining consistent intraocular pressure measurements remains paramount, and patients should be encouraged to discuss any alternative therapies with their ophthalmologist. This collaborative approach ensures that any potential benefits are maximized while safeguarding ocular health.

Carmelita Smith

12 Nov 2025

Acupuncture looks promising for eye pressure, and it’s low‑risk 🙂