Weight Management During Psychotropic Medications: What Works and What Doesn’t

Psychotropic Medication Weight Gain Calculator

Medication Risk Assessment

Select your current or planned psychiatric medication to see estimated weight gain risks and alternative options.

Important: This tool provides general information based on clinical studies. Always discuss medication options with your psychiatrist.

When you start taking a psychotropic medication-whether it’s for depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia-the goal is to feel better. But for many people, the relief comes with an unwanted side effect: weight gain. It’s not just about clothes fitting tighter. This isn’t cosmetic. It’s a medical issue that can shorten your life. People with serious mental illness already live 10 to 20 years less than the general population. A big part of that gap? Medication-related weight gain and its ripple effects: high blood sugar, high cholesterol, heart disease.

Why Do Psychotropic Medications Make You Gain Weight?

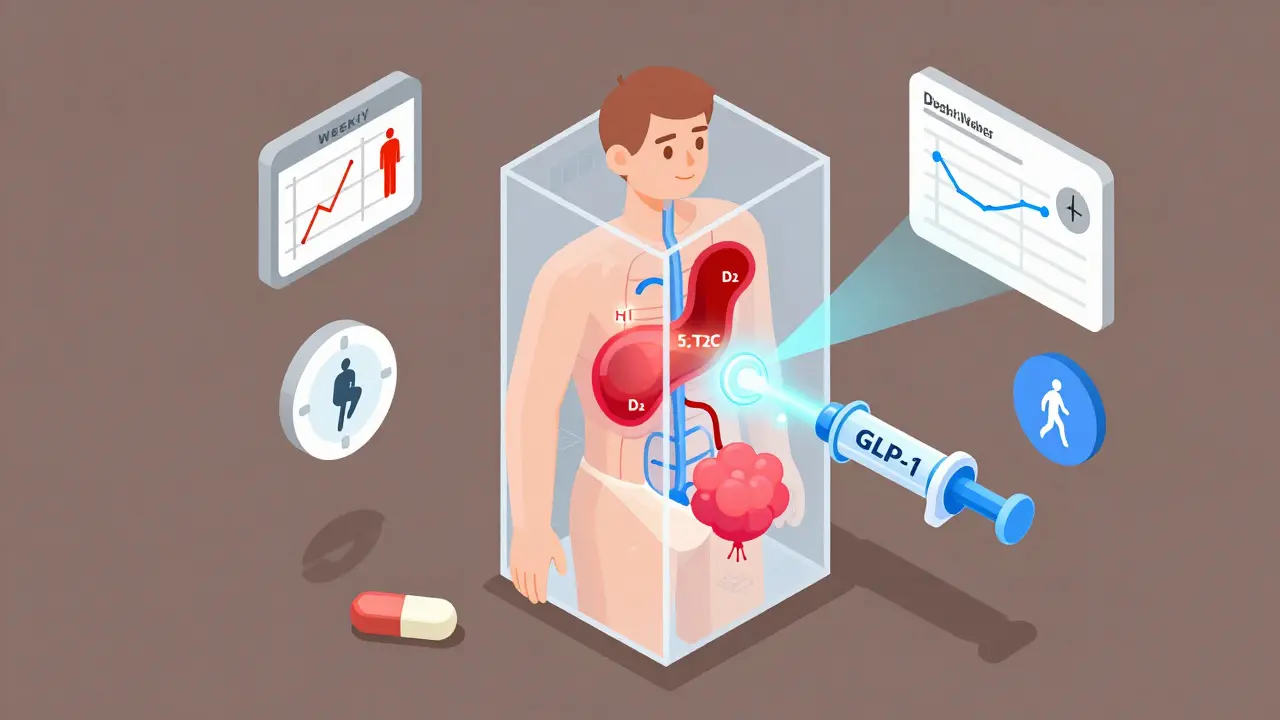

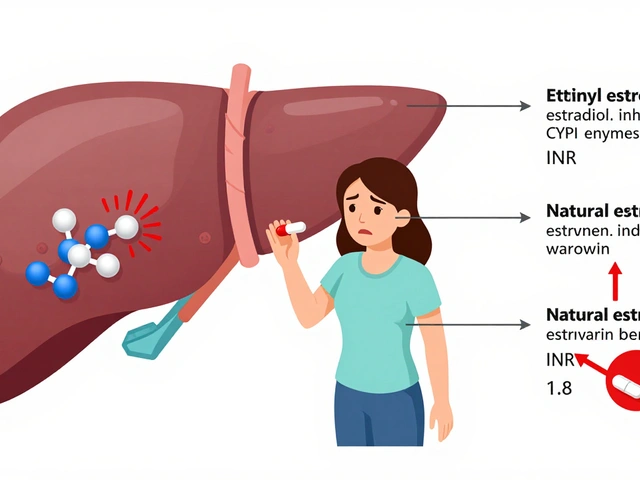

It’s not laziness. It’s not lack of willpower. It’s biology. These drugs affect receptors in your brain that control hunger, metabolism, and energy use. The main culprits are histamine-1, serotonin-2C, and dopamine-2 receptors. When these get blocked, your body thinks it’s starving-even when you’re eating normally. Your appetite spikes. Your metabolism slows. Fat storage increases. Some medications are far worse than others. Clozapine and olanzapine are the biggest offenders. Studies show people on these drugs gain an average of 4 kilograms in just 10 weeks. By the end of the first year, 10 kilograms isn’t unusual. That’s over 20 pounds. Meanwhile, drugs like lurasidone and aripiprazole cause barely any weight gain-sometimes less than placebo. Even antidepressants can do this. Mirtazapine, amitriptyline, and paroxetine are known for packing on pounds. Mood stabilizers like lithium and valproate? Same story. No psychotropic drug is truly weight-neutral over the long term. But the differences between them are huge-and they matter.Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone gains weight the same way. Two people on the exact same dose of olanzapine can have wildly different results. One gains 15 pounds. The other stays the same. Why? Genetics play a role. Early research points to variations in the MC4R gene, which regulates appetite. Some people are just wired to be more sensitive to the hunger signals these drugs trigger. Age, sex, and baseline weight also matter. Younger patients and those already overweight when they start treatment are more likely to see rapid gains. But it’s not just biology. Lifestyle gets tangled up too. Depression and psychosis often reduce motivation. Exercise drops. Healthy eating becomes harder. Sleep gets disrupted. And when your brain is fighting to stay stable, your body isn’t in the mood to diet.What Happens When You Try to Lose Weight on These Drugs?

Here’s the hard truth: losing weight while on psychotropics is harder than you think. A 2016 study tracked 885 people in a weight-loss program. Half were on psychiatric meds. The others weren’t. After 12 months, the group on meds lost 1.6% less weight. Only 63% of them hit the 5% weight loss goal-compared to 71% of those not on meds. And just 32% lost 10% or more, versus 41% in the other group. Why? The drugs change your metabolism at a cellular level. Your body resists fat loss. Hunger hormones stay elevated. Energy expenditure drops. Even when you’re eating right and moving, your body fights back harder. This isn’t a failure. It’s a physiological barrier. That’s why standard weight-loss advice-eat less, move more-often fails here. You need a smarter, more tailored approach.

What Can You Actually Do?

There are three proven paths: switch meds, add meds, or change lifestyle. Sometimes, all three. Switching medications can be powerful. If you’re on olanzapine and gaining weight fast, switching to lurasidone or aripiprazole might help you lose 2-5 kilograms without losing psychiatric control. But this isn’t simple. Some meds work better for your symptoms than others. Never switch without your psychiatrist. A bad switch can trigger relapse. Adding a weight-loss medication is another option. Metformin, originally for diabetes, has been shown in multiple trials to cut antipsychotic-related weight gain by 2-4 kg. It improves insulin sensitivity and reduces appetite. Topiramate, an anti-seizure drug, can help too-studies show 3-5 kg loss on average. Both are used off-label for this purpose and are generally safe when monitored. Newer options are emerging. GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic) and liraglutide (Victoza), which were developed for type 2 diabetes, are now being tested in psychiatric populations. Early results show 5-8% body weight loss in people on antipsychotics. This isn’t standard yet, but it’s coming fast. Lifestyle changes need to be structured, not vague. “Eat healthy” doesn’t cut it. You need:- Weekly sessions with a dietitian who understands psychiatric meds

- Meal plans that account for increased appetite and cravings

- Exercise tailored to your energy levels-walking, swimming, or yoga are often better than intense gym routines

- Behavioral therapy to manage emotional eating triggered by anxiety or low mood

Monitoring Is Non-Negotiable

If you’re on a psychotropic, you need regular check-ins-not just for your mood, but for your body. The American Psychiatric Association recommends:- Baseline weight, waist size, blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol before starting

- Repeat measurements every 3 months

- Track changes over time-not just one number

Comments (14)

Siobhan K.

21 Dec 2025

This is one of those posts that makes you realize how little the medical system actually cares about the whole person. We talk about mental health like it’s a standalone issue, but your body is not a separate system. The fact that we’re still treating weight gain as a ‘side effect’ instead of a core treatment outcome is insane.

And yet, here we are-patients expected to just ‘try harder’ while their meds are literally rewiring their hunger signals. It’s like being told to run a marathon with weights strapped to your legs and then being judged for not finishing.

Metformin isn’t a ‘hack.’ It’s a physiological necessity for so many of us. Why isn’t it standard protocol?

I’ve seen people quit their meds because they couldn’t face the mirror anymore. That’s not willpower-it’s survival.

Brian Furnell

23 Dec 2025

From a pharmacodynamic standpoint, the H1, 5-HT2C, and D2 receptor antagonism is well-documented as the primary driver of metabolic dysregulation in second-generation antipsychotics; however, the downstream effects on adipocyte differentiation and insulin signaling pathways are significantly underappreciated in clinical practice.

Studies utilizing DEXA scans reveal that even ‘modest’ weight gain correlates with visceral adiposity increases exceeding 20% in 12 months-this is not ‘fat gain,’ it’s ectopic lipid deposition in the liver and skeletal muscle, directly contributing to insulin resistance.

Metformin’s efficacy is not merely appetite suppression-it’s AMPK activation and mitochondrial biogenesis enhancement. Topiramate’s GABAergic modulation and carbonic anhydrase inhibition further reduce carb cravings and promote ketone utilization. These aren’t ‘weight-loss drugs’-they’re metabolic stabilizers.

GLP-1 agonists? Yes, but cost and access remain prohibitive. We need policy reform, not just pill prescriptions.

Orlando Marquez Jr

23 Dec 2025

It is imperative to acknowledge the profound public health implications associated with medication-induced metabolic syndrome in populations diagnosed with severe mental illness. The disparity in life expectancy is not merely anecdotal; it is statistically significant and clinically preventable.

Structured multidisciplinary care models, such as those implemented by the Veterans Health Administration, demonstrate measurable improvements in metabolic biomarkers, adherence rates, and patient-reported quality of life.

Standardization of baseline and quarterly metabolic screening should be considered a clinical best practice, not an optional intervention. Institutional protocols must be updated to reflect this evidence.

Furthermore, patient education materials must be revised to emphasize agency and collaboration, rather than blame or passive compliance.

Jackie Be

25 Dec 2025

I gained 40lbs on olanzapine and no one told me it was gonna happen like that

I thought it was me being lazy but no it was the damn drug

Now I’m on lurasidone and I’ve lost 20lbs without even trying

DOCTOR WHY DIDNT YOU TELL ME THIS WAS A THING

also metformin is a miracle worker dont let anyone tell you otherwise

my waist size went from 40 to 32 in 6 months and I just walked 30 mins a day

they want you to suffer so they can keep selling you the same meds

ask for the good ones

Cameron Hoover

25 Dec 2025

I just want to say-this post gave me hope. I’ve been on meds for 8 years and thought I’d never get back to a healthy weight. But hearing that switching to aripiprazole helped others? That’s real. I’m going to talk to my psychiatrist next week.

Also, tracking my waist size every month? I started last week. It’s small, but it’s something. I’m not giving up.

You’re not broken. Your treatment plan is just outdated. And that’s fixable.

Jason Silva

26 Dec 2025

Big Pharma knows this is happening and they don’t care 🤡

They make billions off the weight gain side effects because then they sell you metformin, then GLP-1 drugs, then insulin, then heart meds

It’s a money machine

They don’t want you to know about lurasidone because it’s generic and cheap

They want you dependent on the expensive ones that make you fat

And don’t get me started on the FDA

They’re asleep at the wheel 😤

Check your meds. Ask for alternatives. Fight back.

✊

mukesh matav

26 Dec 2025

This is very informative. I am from India and many patients here do not even get basic metabolic screening. It is a privilege to have access to this information. Thank you for writing this clearly. I will share it with my cousin who is on olanzapine.

Peggy Adams

27 Dec 2025

Ugh I’m so tired of being told to ‘eat less and move more’ like I’m some lazy sloth

My brain is already fighting to stay stable

Now you want me to also be a fitness influencer?

Thanks but no thanks

Also why is everyone acting like metformin is a miracle cure? I tried it and got diarrhea for a month

Not all of us can just ‘switch meds’ either

Some of us are on the only thing that stops the voices

Sarah Williams

28 Dec 2025

My doctor didn’t mention weight gain until I cried in his office because I couldn’t fit into my jeans. Then he handed me a pamphlet.

Turns out, the right combo-lurasidone + metformin + walking with my dog-changed everything.

You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to start.

And you deserve to feel good in your body. Not just your mind.

Theo Newbold

30 Dec 2025

Let’s be honest: the entire psychiatric establishment is built on the illusion of control. They prescribe drugs that cause metabolic collapse, then pat themselves on the back for ‘managing’ the side effects with more drugs.

This isn’t medicine. It’s damage mitigation disguised as care.

The fact that GLP-1 agonists are now being studied as ‘add-ons’ proves the original prescriptions were flawed from the start.

They’re not treating illness. They’re managing the consequences of their own therapeutic failures.

And you’re paying for it-in weight, in health, in dignity.

Jay lawch

30 Dec 2025

Western medicine has failed us. They push these drugs like they’re candy and then act shocked when the body rebels. This is not biology-it’s chemical warfare disguised as treatment. The pharmaceutical companies are not your allies. They are profit-driven entities with zero regard for your longevity. The government allows this because they are complicit. The WHO, the APA, the FDA-they are all part of the same machine that values profit over human life. In India, we see this more clearly: our people are dying from preventable drug-induced diabetes while Western doctors prescribe more pills. This is colonial medicine. They give you a drug to silence your mind, then charge you for the side effects. You are not broken. The system is.

Christina Weber

1 Jan 2026

There are multiple grammatical errors in this post, including the misuse of the plural form 'meds' as a standalone noun without context, inconsistent capitalization of drug names (e.g., 'olanzapine' vs. 'Ozempic'), and improper punctuation around parenthetical statements. Additionally, the claim that 'no psychotropic drug is truly weight-neutral over the long term' is an overgeneralization unsupported by longitudinal studies of bupropion and vortioxetine, which demonstrate statistically insignificant weight changes in controlled trials. The tone is alarmist and lacks academic rigor. This is not a reliable source for clinical decision-making.

Cara C

1 Jan 2026

I just want to say-you’re not alone. I’ve been where you are. The shame, the frustration, the feeling that your body betrayed you.

But here’s the truth: you’re not failing. The system is.

It’s okay to ask for help. It’s okay to want to feel good in your skin. It’s okay to ask your doctor for alternatives.

You don’t have to choose between your mind and your body. You deserve both.

Start small. Track one thing. Talk to one person. You’ve already taken the hardest step-you’re here, reading this.

That matters.

Siobhan K.

1 Jan 2026

Christina Weber-your nitpicking about grammar is exactly why this system stays broken.

People aren’t reading peer-reviewed journals. They’re reading this because they’re scared, tired, and alone.

When your body is changing and no one listens, you don’t need perfect punctuation.

You need someone to say: ‘I see you. This isn’t your fault.’

So thanks for the critique.

But thanks even more to the person who wrote this post.

They saved someone today.