Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: What You Need to Know About These Life-Threatening Drug Reactions

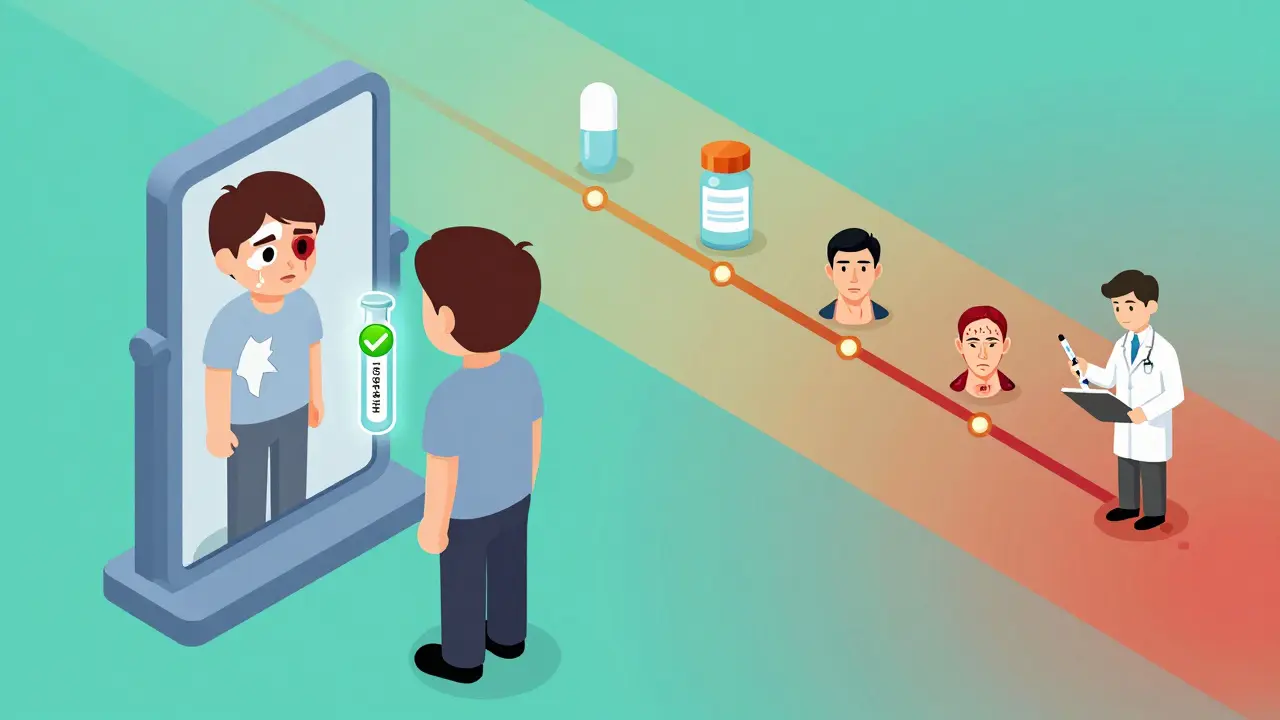

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) aren’t just rare skin rashes. They’re medical emergencies that can turn a simple medication into a life-or-death situation. Imagine waking up with a fever and sore throat, then watching your skin start to blister and peel off like a sunburn gone horribly wrong. That’s what SJS and TEN look like - and they happen faster than most people expect.

It’s One Disease, Not Two

For decades, doctors thought SJS and TEN were separate conditions. But today, they’re understood as points on the same deadly spectrum. The only real difference? How much of your skin dies.If less than 10% of your body surface area loses its outer skin layer, it’s called SJS. Between 10% and 30%? That’s the overlap form. More than 30%? That’s TEN - the most severe version. In TEN, large sheets of skin detach, leaving raw, open wounds that look like third-degree burns. And it’s not just your skin. Your eyes, mouth, throat, and genitals are almost always involved too.

These aren’t allergic reactions like hives. They’re immune system attacks on your own skin. Your body’s T cells and natural killer cells go rogue, triggering a chain reaction that kills skin cells from the inside out. The result? Full-thickness epidermal necrosis - meaning your skin doesn’t just get irritated, it literally dies and peels away.

How It Starts: The Silent Warning Signs

Most people don’t realize they’re in danger until it’s too late. The first signs are easy to miss. You get a fever - maybe 102°F or higher. You have a headache. Your throat hurts. You feel like you’re coming down with the flu. Maybe your eyes feel gritty or red.This phase lasts one to three days. Then, without warning, flat red or purple spots appear on your chest or back. They spread fast - within 24 to 72 hours - and turn into blisters. The skin becomes tender, painful, and starts to slough off. If you press on the edge of a blister and the surrounding skin peels away, that’s called the Nikolsky sign. It’s a red flag doctors look for.

And here’s the catch: this reaction usually happens 1 to 3 weeks after you started a new medication. But if you’ve had it before and get exposed again, it can hit in under 48 hours. That’s why knowing your history matters.

What Drugs Cause It?

Over 80% of cases are caused by medications. The biggest culprits? A few specific drugs that most people take without knowing the risk.- Antiepileptics: Carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine - these are common for seizures and bipolar disorder. Together, they cause about 30% of cases.

- Sulfonamide antibiotics: Like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Used for UTIs and sinus infections. Responsible for 20% of cases.

- Allopurinol: Taken for gout. Causes 15% of cases - and the risk skyrockets if you have a certain gene.

- NSAIDs: Ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib. Even over-the-counter painkillers can trigger it.

- Nevirapine: An HIV drug with high risk in certain populations.

But here’s the most important part: genetics play a huge role. If you carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene - common in people of Asian descent - taking carbamazepine increases your risk of SJS/TEN by up to 1,000 times. The HLA-B*58:01 gene does the same for allopurinol, increasing risk by 80 to 580 times. That’s why the FDA now recommends genetic testing before prescribing these drugs to high-risk groups. In Taiwan, mandatory screening cut SJS/TEN cases by 80% in just a few years.

Diagnosis: Why Skin Biopsy Is Essential

There’s no single blood test for SJS/TEN. You can’t diagnose it with a quick scan. The gold standard? A skin biopsy.Under the microscope, doctors look for full-thickness death of the epidermis - the top layer of skin - with almost no inflammation underneath. That’s what separates it from other blistering diseases like staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, which affects children and has a different pattern of skin splitting.

Doctors also use the RegiSCAR criteria: acute onset, skin tenderness, mucosal involvement, and typical lesions. If you have blisters, peeling skin, and mouth or eye sores after starting a new drug - it’s SJS/TEN until proven otherwise.

How It’s Treated: Time Is Everything

There’s no cure. But survival depends on one thing: speed.Step one: Stop every non-essential medication. Right now. Even if you’re not sure which one caused it. The sooner you stop the trigger, the better your chances.

Step two: Get to a burn unit or ICU. These patients lose fluids like burn victims - sometimes three to four times the normal amount. They need aggressive IV hydration. They need sterile, non-stick dressings. They need pain control that actually works.

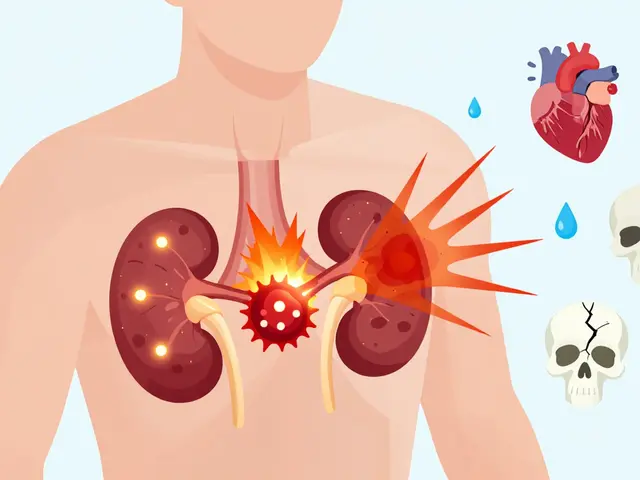

Step three: Manage the complications. Your eyes are at high risk. Without daily ophthalmology care, you could develop scarring, dry eyes, or even blindness. Your mouth is so raw you can’t eat. Your lungs might get infected. Your kidneys might fail.

As for drugs to treat it? The evidence is mixed. IVIG (intravenous immune globulin) was once thought to help - but large studies showed no survival benefit. Steroids? They might reduce inflammation, but they also raise your risk of deadly infections. Cyclosporine, an immune suppressor, showed promise in a 2016 trial - cutting death rates from 33% to 12.5%. And etanercept, a TNF-alpha blocker, had zero deaths in a small 2019 study when given within 48 hours.

There’s no universal protocol. But the trend is clear: targeted immune therapies are the future.

What Happens After You Survive

Surviving SJS/TEN doesn’t mean you’re back to normal. Far from it.Up to 80% of survivors deal with long-term problems:

- Eye issues: 50-80% have chronic dry eyes, light sensitivity, or corneal scarring. Some need lifelong eye drops or even surgery.

- Skin changes: 70% have patchy dark or light spots. 40% have permanent scarring. 25% lose nails or grow them deformed.

- Genital problems: 15% develop urethral strictures. 10% get vaginal adhesions - both requiring surgical repair.

- Psychological trauma: 40% develop PTSD. The pain, the isolation, the fear - it sticks with you.

Recovery takes months. Some people need years of follow-up care. And for many, the fear of another reaction never fully goes away.

Can You Prevent It?

Yes - but only if you know your risk.If you’re of Asian descent and your doctor wants to prescribe carbamazepine, ask for HLA-B*15:02 testing. If you have gout and they’re suggesting allopurinol, ask about HLA-B*58:01. These tests are fast now - some labs can return results in four hours. In 2022, the FDA approved a point-of-care test for allopurinol patients. That’s a game-changer.

Also, if you’ve ever had a bad skin reaction to a drug - even a mild rash - tell every doctor you see. Don’t assume it’s “just an allergy.” Write it down. Bring it up. It could save your life.

And if you’re prescribed a new medication, watch for those early warning signs: fever, sore throat, eye redness. If you start getting a rash within a few weeks - don’t wait. Go to the ER. SJS/TEN doesn’t wait.

Why This Matters

SJS and TEN affect only 1 to 6 people per million each year. That sounds rare. But when it happens to you - or someone you love - it’s not rare anymore. It’s terrifying. It’s devastating. It’s life-changing.These conditions show how powerful drugs can be - not just as medicine, but as weapons turned inward. They remind us that even common prescriptions carry hidden risks. And they prove that personalized medicine isn’t just a buzzword - it’s a lifeline.

Genetic testing, faster diagnostics, better treatments - they’re all here. But they only work if patients and doctors talk. If you take a pill, know what you’re taking. If you feel something wrong, speak up. Your skin might be the first to scream - listen to it.

Can Stevens-Johnson Syndrome be caused by infections?

Yes, though it’s rare. About 10% of pediatric cases are triggered by infections, especially Mycoplasma pneumoniae - the bacteria that causes walking pneumonia. In adults, infections are much less common as a cause. Most cases - over 80% - are linked to medications. But if you develop a rash after a viral or bacterial illness, especially with mouth or eye sores, it’s still important to get checked.

Is Stevens-Johnson Syndrome contagious?

No. SJS and TEN are not contagious. You can’t catch them from someone else. They’re caused by your own immune system reacting to a drug or, rarely, an infection. Being around someone with SJS/TEN poses no risk to you - unless you’re taking the same medication and have the same genetic risk.

How long does it take to recover from Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis?

The acute phase lasts 8 to 12 days, but full recovery takes months to years. Skin regrows over 2 to 4 weeks, but scars, pigment changes, and organ damage can last much longer. Many survivors need ongoing care for eye, skin, or genital complications. Psychological recovery is often the longest part - with up to 40% developing PTSD after the trauma of hospitalization.

Can you get SJS/TEN from over-the-counter drugs?

Yes. While most cases come from prescription drugs like antiepileptics or antibiotics, over-the-counter NSAIDs - such as ibuprofen, naproxen, or celecoxib - have also been linked to SJS/TEN. Even common pain relievers can trigger a reaction in genetically susceptible people. Never assume OTC means safe.

What’s the survival rate for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis?

About 25% of people with TEN die, mostly from sepsis, organ failure, or pneumonia. Survival depends on how quickly treatment starts and how much skin is affected. The SCORTEN scale predicts mortality based on factors like age, heart rate, and blood values. If three or more risk factors are present, survival drops to about 65%. With five or more, it’s less than 10%.

Are there new treatments for SJS/TEN on the horizon?

Yes. Researchers are testing drugs that block granulysin, a protein that kills skin cells in SJS/TEN. Phase II trials are expected to begin in 2024. Other promising approaches include targeted biologics like etanercept, which showed 0% mortality in early studies when given within 48 hours. Genetic screening is also expanding - with faster, cheaper tests now available to prevent reactions before they start.

Comments (8)

Natasha Sandra

25 Dec 2025

OMG this is so important!! 🙏 I had a friend go through this after taking ibuprofen for a headache… she lost 30% of her skin and spent 3 months in the hospital. No one warned her. Please, if you’re on any med and get a rash + fever-GO TO THE ER. Don’t wait. 💔

Erwin Asilom

26 Dec 2025

The clinical distinction between SJS and TEN as a spectrum is well-established in dermatology literature since the early 2000s. The key clinical marker remains the extent of epidermal detachment. Early cessation of the offending agent and transfer to a burn unit are the only evidence-based interventions with proven impact on mortality.

sakshi nagpal

28 Dec 2025

As someone from India, I’m glad to see HLA-B*58:01 mentioned. My uncle passed away from allopurinol-induced TEN in 2018. We never knew about the genetic link. Now, my entire family gets tested before any new prescriptions. It’s not just about medicine-it’s about awareness. Thank you for writing this.

Sandeep Jain

30 Dec 2025

i had a rash once after taking bactrim and thought it was no big deal… turns out i was lucky. this post scared the crap outta me but also made me wanna tell everyone. if u got a fever + rash after a new med? stop it. go. now. my cousin died from this and no one knew it could happen from antibiotics.

roger dalomba

30 Dec 2025

Ah yes, the classic ‘I read a 2000-word medical article and now I’m an immunologist’ post. Congrats. You’ve unlocked the ‘I’m saving lives by posting this’ badge. 🎖️

Amy Lesleighter (Wales)

1 Jan 2026

this is why we need to stop treating meds like candy. your body isn’t a machine you can just plug in a new part and it works. sometimes it just… breaks. and when it does, you’re left with scars you can’t see. i’m not saying don’t take meds. i’m saying know your body. know your genes. listen to your skin. it talks before you feel the pain.

Rajni Jain

2 Jan 2026

thank you for sharing this. i’m a nurse and i’ve seen this happen too many times. families blame the doctor, but no one told them about the genetic risks. please, if you’re asian and your doc wants to give you carbamazepine-ask for the test. it takes 15 mins. it could save your life. i wish someone had told me sooner.

Brittany Fuhs

3 Jan 2026

Of course the FDA only acts after people die. Meanwhile, in America, we’re still prescribing allopurinol like it’s aspirin. And yes, I’m Indian. And yes, I had the gene. And yes, I’m still mad they didn’t test me before I nearly died. 🇺🇸 #NotAllAmericansAreStupid