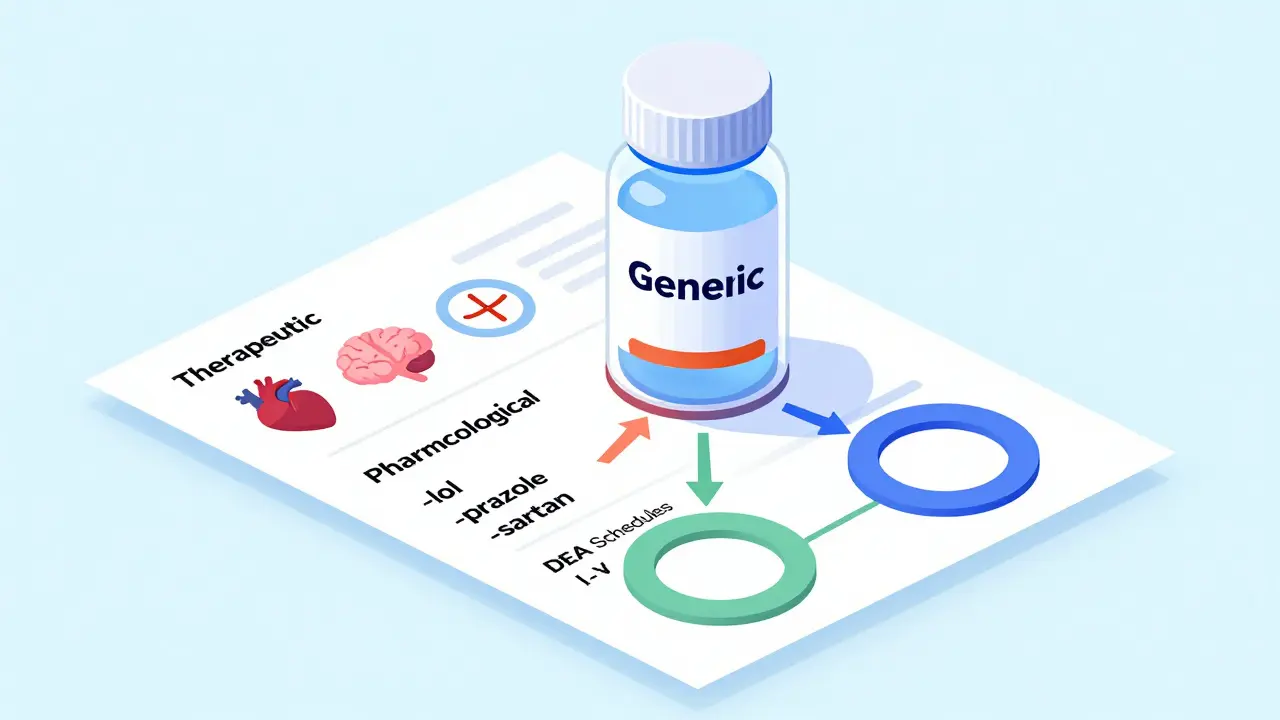

Generic Drug Classifications: Types and Categories Explained

When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might see a label that says generic - but what does that actually mean beyond saving money? Generic drugs aren’t just cheaper versions of brand-name pills. They’re classified into specific types and categories that tell doctors, pharmacists, and patients how they work, what they treat, and how they’re regulated. Understanding these classifications isn’t just for experts - it affects your treatment, your costs, and even your safety.

Therapeutic Classification: What the Drug Is Used For

The most common way drugs are grouped is by what condition they treat. This is called therapeutic classification. It’s simple: if a drug helps lower blood pressure, it’s a cardiovascular agent. If it reduces pain, it’s an analgesic. This system is used in 98% of U.S. hospitals because it’s practical for daily decisions.

Major therapeutic categories include:

- Analgesics - pain relievers like acetaminophen (non-opioid) and oxycodone (opioid)

- Antihypertensives - drugs like lisinopril and amlodipine for high blood pressure

- Antidepressants - SSRIs like sertraline and SNRIs like duloxetine

- Antidiabetics - metformin, glipizide, and newer agents like semaglutide

- Antineoplastics - chemotherapy drugs like capecitabine and docetaxel

- Endocrine agents - levothyroxine for thyroid, insulin for diabetes

Each of these has subcategories. For example, antihypertensives include beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers. The problem? Some drugs fit in more than one category. Aspirin, for instance, is both an analgesic and an anticoagulant. That’s why the FDA updated its system in 2023 to allow primary and secondary indications - so a drug can belong to more than one group without confusion.

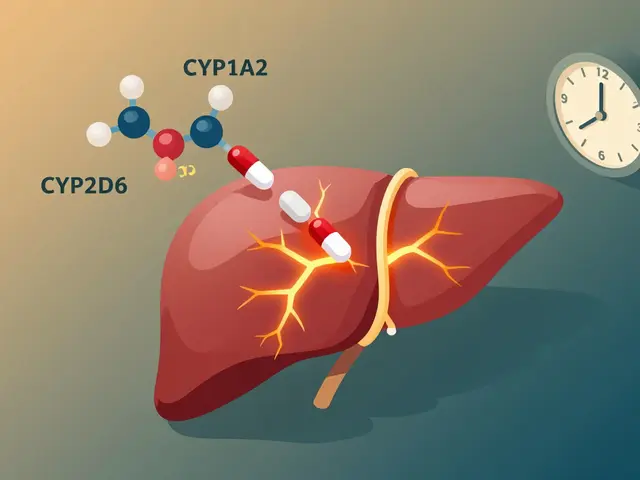

Pharmacological Classification: How the Drug Works

While therapeutic classification asks “what does it do?”, pharmacological classification asks “how does it do it?” This system looks at the drug’s biological mechanism. It’s more technical but essential for understanding side effects and interactions.

For example:

- Drugs ending in -lol - like propranolol or metoprolol - are beta-blockers. They block adrenaline receptors to slow heart rate.

- Drugs ending in -prazole - like omeprazole or esomeprazole - are proton pump inhibitors. They shut down acid production in the stomach.

- Drugs ending in -sartan - like losartan or valsartan - are angiotensin II receptor blockers. They relax blood vessels.

The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) tracks 87 of these naming stems. This isn’t just for memory - it helps prevent errors. A 2022 study showed that using stem conventions reduced medication mistakes by 18%. But it’s not perfect. Newer biologic drugs - like monoclonal antibodies used in cancer or autoimmune diseases - don’t follow these patterns, making classification harder.

There are over 1,200 pharmacological classes identified in current medical literature. For instance, “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Kinase Inhibitors” sounds complex, but it tells you exactly how the drug targets cancer cells. This level of detail is critical for oncologists and researchers - but overwhelming for most patients and even some general practitioners.

DEA Schedules: Legal Status and Abuse Risk

Not all drugs are treated the same under the law. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classifies controlled substances into five schedules based on their potential for abuse and accepted medical use. This system comes from the 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act - and it still governs how prescriptions are written, filled, and tracked.

Here’s how it breaks down:

- Schedule I - No medical use, high abuse potential. Examples: heroin, LSD, marijuana (though this is changing).

- Schedule II - High abuse potential, but medical use. Examples: oxycodone, fentanyl, Adderall, methadone.

- Schedule III - Moderate abuse potential. Examples: ketamine, buprenorphine, some cough syrups with codeine.

- Schedule IV - Low abuse potential. Examples: alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), zolpidem (Ambien).

- Schedule V - Very low abuse potential. Examples: cough medicines with less than 200mg codeine per 100ml.

There’s controversy here. Marijuana is still Schedule I federally, even though it’s legal for medical use in 38 states and FDA-approved drugs like dronabinol (a synthetic THC) are Schedule II. Critics say the system doesn’t reflect science - it reflects politics. A 2021 JAMA study pointed out this inconsistency blocks research into marijuana’s therapeutic benefits.

For patients, this affects access. Schedule II drugs can’t be refilled without a new prescription. Schedule III and IV can be refilled up to five times in six months. This isn’t just bureaucracy - it’s a safety tool.

Insurance Tiers: What You Pay Out of Pocket

Your insurance plan doesn’t care about therapeutic or pharmacological categories - it cares about cost. Most plans use a 5-tier system to control spending. The same generic drug can end up in different tiers depending on your insurer’s contracts with manufacturers.

Here’s how Humana’s system works:

- Tier 1 - Preferred generics. Lowest cost. About 75% of generics fall here. Example: generic lisinopril.

- Tier 2 - Non-preferred generics. Slightly higher copay. Example: generic metformin from a less-preferred supplier.

- Tier 3 - Preferred brand-name drugs. More expensive than generics.

- Tier 4 - Non-preferred brands. High cost, often requiring prior authorization.

- Tier 5 - Specialty drugs. Rare, expensive, complex. Examples: biologics for rheumatoid arthritis or multiple sclerosis.

Here’s the catch: two identical generic pills - same active ingredient, same dosage, same manufacturer - can be in different tiers. Why? Because one was negotiated into a better deal by your insurer. A 2022 KFF analysis found that patients paid 25-35% more for Tier 2 generics than Tier 1, even when the drugs were chemically identical.

Pharmacists report that 43% of prior authorization requests come from tier disputes. Patients get confused: “Why is my $4 generic now $25?” The answer isn’t clinical - it’s financial.

The ATC System: Global Standard for Drug Tracking

While the U.S. uses multiple systems, the World Health Organization’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification is the global gold standard. It’s used in 143 countries and helps track drug use across borders.

The ATC system has five levels:

- Level 1 - Anatomical main group (e.g., A = Alimentary tract and metabolism)

- Level 2 - Therapeutic subgroup (e.g., A10 = Drugs used in diabetes)

- Level 3 - Pharmacological subgroup (e.g., A10B = Blood glucose lowering drugs, excluding insulins)

- Level 4 - Chemical subgroup (e.g., A10BA = Biguanides)

- Level 5 - Chemical substance (e.g., A10BA02 = Metformin)

That means metformin is coded as A10BA02 - a universal identifier. The WHO adds over 200 new ATC codes every year. In 2022 alone, 217 new drugs got codes, including new cancer therapies and mRNA-based treatments. This system is so precise that it’s used in public health research to track prescribing trends, drug shortages, and antibiotic resistance.

Why Classification Matters - And Why It’s Broken

On paper, these systems make sense. In practice, they’re fragmented. A doctor uses therapeutic classification to choose a drug. A pharmacist checks the DEA schedule to know how many refills are allowed. A pharmacist checks the insurance tier to know how much the patient will pay. And the patient? They’re left wondering why the same pill costs $4 one month and $20 the next.

Studies show 68% of physicians feel confused by overlapping systems. Nurses report 47% faster medication checks when classification is consistent - but only 38% of prescribers regularly use official FDA or USP resources. That’s a gap between knowledge and practice.

And it’s getting worse. New drugs - especially those that treat multiple conditions at once - don’t fit neatly into old boxes. A drug might lower blood sugar, reduce weight, and protect the heart. Which category does it belong in? The FDA’s 2023 update tried to fix this with primary-secondary tagging, but adoption is slow.

Meanwhile, AI tools like IBM Watson’s Drug Insight platform are starting to predict the best classification based on real-world data. Early results show 92.7% accuracy. That might be the future - but right now, we’re still stuck with a patchwork of systems that were never meant to work together.

What You Should Know

You don’t need to memorize every classification. But you should understand this:

- If your drug is a generic, it’s chemically identical to the brand - but it might be in a different insurance tier.

- Drugs with names ending in -lol, -prazole, or -sartan follow patterns that tell you how they work.

- If your prescription has a DEA schedule (II, III, IV), it’s controlled. You can’t refill it like a regular pill.

- Always ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same as the one I took last month?” - especially if the price changed.

- Therapeutic classification is your best friend when discussing options with your doctor. Say: “I need something for pain, but not an opioid.” That’s how the system was designed to work.

Classification systems are meant to protect you - not confuse you. But they only work if you know how to use them.

What is the difference between generic and brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs contain the same active ingredient, dosage, strength, and route of administration as their brand-name counterparts. They must meet the same FDA standards for safety, effectiveness, and quality. The only differences are in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes), packaging, and price - generics cost 80-85% less on average.

Why are some generic drugs more expensive than others?

It’s not about the drug - it’s about your insurance plan. Two identical generics can be in different insurance tiers. Tier 1 generics are preferred and cheapest. Tier 2 are non-preferred and cost more, even if they’re chemically the same. This happens because insurers negotiate deals with manufacturers. Always ask your pharmacist if a cheaper alternative exists in Tier 1.

What does it mean if a drug is Schedule II?

Schedule II drugs have a high potential for abuse and dependence but are accepted for medical use. Examples include oxycodone, fentanyl, and Adderall. These prescriptions can’t be refilled - you need a new one each time. They’re tracked in state prescription monitoring programs to prevent misuse. You may be asked for ID or to sign a log when picking them up.

How do drug names tell you what they do?

Many generic drug names use standardized suffixes called stems. For example, drugs ending in -lol are beta-blockers (like propranolol), -prazole means proton pump inhibitor (like omeprazole), and -sartan indicates an angiotensin receptor blocker (like losartan). These stems help healthcare providers quickly identify the drug’s class and mechanism - reducing errors. But newer biologic drugs don’t follow this pattern.

Is the ATC system used in the U.S.?

The ATC system is not officially used by U.S. regulators like the FDA, but it’s widely adopted in research, public health, and international drug tracking. Many U.S. hospitals and pharmacies use ATC codes internally because they’re precise and global. It’s the language of drug data across borders - even if your insurance doesn’t use it.

Can a drug be in more than one classification?

Yes - and that’s a growing problem. Aspirin is both an analgesic and an anticoagulant. Duloxetine treats depression and nerve pain. The FDA’s 2023 update now allows drugs to have a primary and secondary classification. This helps doctors choose the right drug for the right reason, but it’s still not fully integrated into all electronic health records.

Comments (8)

Lu Gao

1 Feb 2026

Love how this breaks down the chaos of drug classification 😊 But can we talk about how Tier 2 generics are basically a scam? My metformin went from $4 to $22 last month-same pill, same pharmacy, same doctor. Insurance just picked a new ‘preferred’ supplier. No clinical difference. Just greed. 💸

Jamie Allan Brown

3 Feb 2026

This is one of the clearest explanations I’ve ever read on how fragmented our drug systems are. I’ve worked in pharmacy for 15 years, and even I get tripped up by tier shifts and dual classifications. The fact that aspirin is both an analgesic and anticoagulant should be common knowledge-but it’s not. We need better training, not just better codes.

Lisa Rodriguez

5 Feb 2026

So many people don’t realize that the same generic can cost 5x more just because of insurance deals. I always ask my pharmacist if there’s a Tier 1 alternative. Sometimes it’s the exact same bottle, just a different label. And yes, the -prazole and -sartan endings? Lifesavers. I use them to guess what my meds do before I even look them up. 🙌

Nicki Aries

6 Feb 2026

It’s alarming, truly alarming, that the FDA’s 2023 update allowing primary and secondary classifications hasn’t been universally adopted-especially in EHRs. The lack of standardization is not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous. One misplaced code, one misread stem, and you’ve got a patient on the wrong drug. We’re not talking about minor errors here. Lives are at stake. And yet, we still rely on paper logs and handwritten notes in some places. This is 2024.

Ed Di Cristofaro

7 Feb 2026

DEA Schedule I for marijuana? That’s just pure politics. People are dying because they can’t get real research done. Meanwhile, Big Pharma makes billions off synthetic THC pills that cost $1,200 a month. The system is rigged. Wake up.

Lilliana Lowe

9 Feb 2026

The ATC system is not merely ‘widely adopted’-it is the only scientifically coherent, globally interoperable framework for pharmaceutical classification. The U.S. refusal to formally integrate it into regulatory infrastructure is not a policy choice; it is a catastrophic failure of administrative modernization. The fact that you refer to it as ‘not officially used’ suggests a profound misunderstanding of international pharmacovigilance standards. Please, do better.

Deep Rank

9 Feb 2026

OMG I just realized my dad’s blood pressure med is both an antihypertensive AND an antidiabetic? Wait no-wait-hold on-so if he’s on lisinopril and he’s also diabetic, does that mean the drug is treating two things at once? But then why does his insurance put it in Tier 2? And why does the pharmacist keep asking if he wants the ‘other’ lisinopril? I think I’m having a breakdown. Also I read somewhere that metformin might help with weight loss but I’m not sure if that’s true or just TikTok? And what about the -prazole thing? I think I’m confused now. Also my cousin’s Adderall is Schedule II but his cousin’s is Schedule IV? I think I need to lie down.

Ishmael brown

9 Feb 2026

Actually, the FDA’s 2023 update didn’t fix anything. It just added more layers. The real problem? Nobody’s using AI tools like Watson Drug Insight. Why? Because the industry’s too slow. And the worst part? Pharmacists still rely on paper formularies. It’s like we’re still using rotary phones to order insulin. I’ve seen it. I’ve cried about it. And no one listens.