How Sarcoptes scabiei Triggers Allergies and Skin Sensitivities

Scabies vs. Allergy Symptom Checker

Symptom Assessment

This tool helps determine if your skin symptoms might be related to scabies or a classic allergy. Answer the following questions to get an assessment based on clinical criteria.

Results

Quick Takeaways

- Sarcoptes scabiei can act like an allergen, causing hives, itching and eczema‑like flare‑ups.

- The mite’s proteins stimulate IgE antibodies and histamine release, the same pathway as classic allergies.

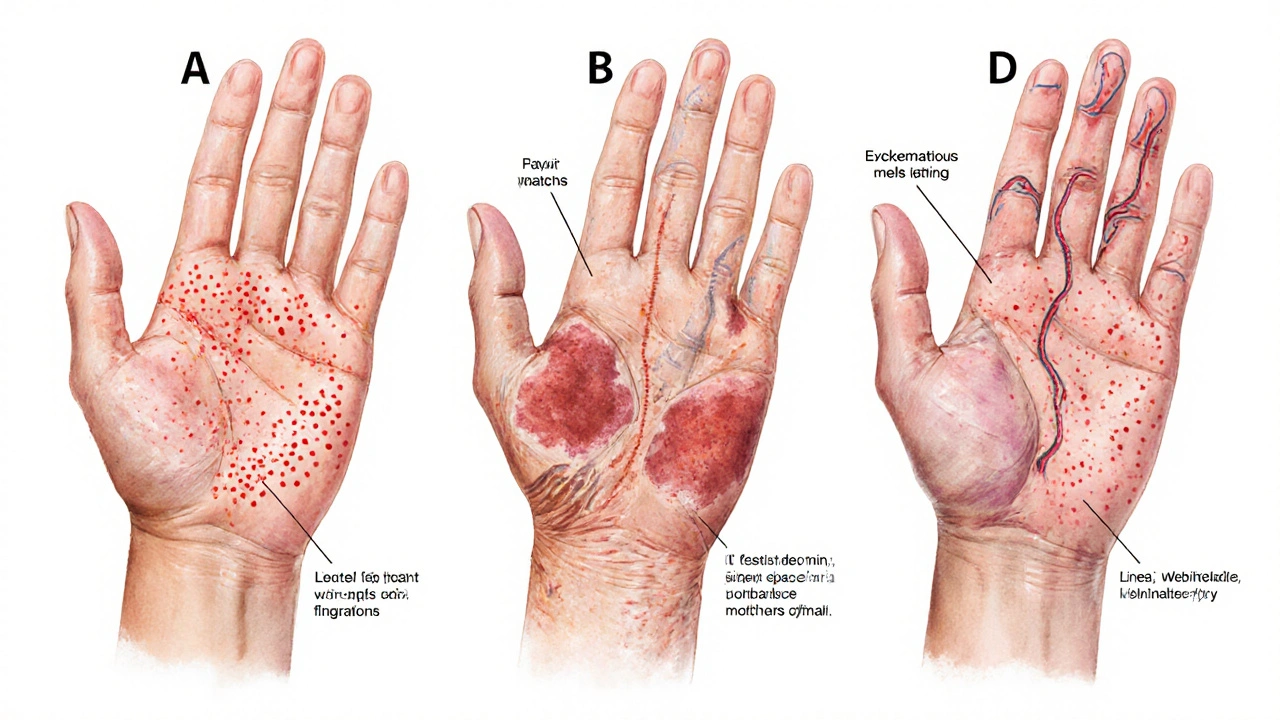

- Distinguishing a pure allergic rash from scabies‑induced skin sensitivity relies on burrow patterns, timing and lab tests.

- Effective treatment combines anti‑mite medication with antihistamines or topical steroids to calm the immune response.

- Early consulting with a dermatologist prevents chronic crusted scabies and long‑term skin damage.

When you hear the word scabies, the first image that pops up is often a red, itchy rash spreading across the body. But for many people the story doesn’t stop at a simple infestation. The tiny mite behind the disease, Sarcoptes scabiei a microscopic arthropod that burrows into the superficial skin layers to lay its eggs, can also set off an allergic cascade that looks a lot like classic hay‑fever or food‑allergy reactions. Understanding how this parasite interacts with the immune system the body’s network of cells and chemicals that defend against foreign invaders is the key to untangling the overlap between scabies and skin sensitivities.

What is Sarcoptes scabiei?

The adult female mite measures about 0.3‑0.4mm-still visible to the naked eye as a tiny speck. It digs a shallow tunnel, called a burrow, inside the stratum corneum, the outermost skin layer. Inside the tunnel the mite lays 1‑2 eggs per day, which hatch into larvae that continue the cycle. The whole life span lasts roughly 4‑6 weeks, but the itching can linger much longer because the body’s response doesn’t shut off when the mites die.

How the Mite Triggers an Allergic Response

Allergies are driven by a specific type of antibody called IgE an immunoglobulin that binds to allergens and alerts mast cells to release histamine. When Sarcoptes scabiei burrows, it releases a cocktail of proteins, enzymes, and waste products. In susceptible individuals these proteins act as allergens:

- They are taken up by skin‑resident dendritic cells, which travel to lymph nodes and present fragments to T‑helper 2 cells.

- Those T‑cells urge B‑cells to produce IgE specifically targeting mite antigens.

- IgE‑coated mast cells sit in the skin, ready to degranulate when they encounter even a tiny amount of the mite protein again.

The result is a rapid release of histamine a compound that widens blood vessels and stimulates nerve endings, causing itching and swelling, along with other mediators like leukotrienes. This biochemical storm looks exactly like an allergic rash even after the mites have been cleared.

Skin Sensitivities That Often Co‑Occur with Scabies

Because the allergic pathway mirrors other hypersensitivity reactions, patients frequently report the following alongside classic scabies lesions:

- Urticaria (hives): Raised, red welts that appear suddenly and may migrate across the body.

- Atopic dermatitis flare‑ups: Chronic eczema patches become red, oozing and intensely itchy.

- Contact dermatitis-like rash: Linear streaks where the mite’s burrow scratches the skin.

- Hyper‑reactive skin: Even light fabrics or heat trigger burning sensations.

These manifestations are often misdiagnosed as separate allergic conditions, delaying the proper anti‑mite therapy.

Diagnosing the Overlap: Allergy vs. Scabies

Clinicians use a combination of visual cues, patient history, and laboratory tests to separate pure allergy from scabies‑induced sensitivity.

| Feature | Allergy‑Only | Scabies‑Related |

|---|---|---|

| Typical pattern | Diffuse, no burrows | Linear or serpentine burrows, often in web spaces |

| Onset after exposure | Immediate (minutes‑hours) | Delayed (days‑weeks) as mite population grows |

| Night‑time itching | Variable | Common, often severe at night |

| Response to antihistamines | Good | Partial - need anti‑mite treatment |

| Skin scraping test | Negative | Positive for mites or eggs |

Skin scrapings examined under a microscope remain the gold standard for confirming Sarcoptes scabiei. In ambiguous cases, a dermatologist may order a dermatoscopic examination or a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for mite DNA.

Managing the Dual Challenge

Effective therapy tackles both the parasite and the immune reaction. A typical regimen includes:

- Topical scabicidal agents: Permethrin 5% cream applied overnight for 8-14hours, repeated after one week.

- Oral ivermectin: 200µg/kg dose on day1 and day2 for widespread or crusted disease.

- Antihistamines: Second‑generation cetirizine or fexofenadine to curb histamine‑driven itching.

- Topical corticosteroids: Low‑potency hydrocortisone 1% for inflamed skin patches, used sparingly to avoid skin thinning.

- Moisturizers and barrier creams: Re‑hydrate cracked skin and reduce secondary bacterial infection risk.

For patients with a history of atopic dermatitis, adding a short course of a medium‑potency steroid (e.g., betamethasone 0.05%) can break the itch‑scratch cycle. In resistant cases, an oral antihistamine combined with a brief steroid taper is often required.

When to Seek Professional Help

If any of the following apply, book an appointment with a dermatologist a medical specialist trained in skin disorders promptly:

- Rash has persisted beyond two weeks despite over‑the‑counter creams.

- Signs of secondary infection: pus, crusting, fever.

- Family members or close contacts develop similar itching.

- History of immune‑mediated skin disease (e.g., eczema, psoriasis).

Early intervention not only clears the infestation but also reduces the risk of developing crusted scabies a severe form with thickened skin and massive mite load, which can be life‑threatening for immunocompromised patients.

Prevention Tips to Keep the Mite at Bay

- Wash all bedding, clothing, and towels in hot water (≥60°C) and tumble‑dry on high heat.

- Vacuum carpets and upholstered furniture thoroughly after treatment.

- Avoid sharing personal items such as socks, shoes, or scarves.

- For households with infants, use cotton mittens to stop babies from scratching burrows.

- Regularly inspect skin in high‑risk environments (e.g., nursing homes, refugee camps).

FAQ - Frequently Asked Questions

Can an allergic reaction to scabies persist after the mites are gone?

Yes. The IgE antibodies produced during infestation can remain active for weeks, so itching may continue even when the mites have been eradicated. Continuing antihistamines and skin‑soothing moisturizers helps until the immune response subsides.

Is it safe to use permethrin if I have eczema?

Permethrin is generally safe for eczema‑prone skin, but applying a thin layer of moisturizer afterward can prevent excessive dryness. If you notice worsening redness, talk to your dermatologist about a combined steroid‑permethrin regimen.

Why do my children develop hives after a scabies outbreak?

Children’s immune systems are more reactive. The mite’s proteins can act as a potent allergen, triggering hives (urticaria) as a secondary reaction. Treating the scabies and using an antihistamine usually resolves the hives.

How is crusted scabies different from ordinary scabies?

Crusted scabies features thick, scaly plaques teeming with millions of mites, whereas ordinary scabies usually has 10‑15 mites per person. Crusted scabies spreads more easily and requires multiple doses of oral ivermectin plus intense topical therapy.

Do I need to treat my pets for scabies?

Pets get a different species called Sarcoptes canis. While it doesn’t jump to humans, close contact can lead to simultaneous infestations, so a veterinarian check is advisable.

Next Steps If You Suspect an Allergy‑Mite Connection

- Inspect common bite sites (wrists, elbows, web spaces) for tiny burrows.

- Collect a skin scraping and bring it to a clinic for microscopic analysis.

- Start a 5% permethrin cream regimen while you wait for results.

- Add a non‑sedating antihistamine if itching interferes with sleep.

- Schedule a follow‑up with a dermatologist within a week to review response and adjust treatment if needed.

Following this plan tackles both the parasite and the allergic inflammation, giving you the best chance for a swift, itch‑free recovery.

Comments (8)

Darius Reed

14 Oct 2025

Man, those scabies mites are like tiny ninja burglars that set off a fireworks show in your skin. I swear the itching feels like a hundred tiny rubber chickens doing the cha‑cha on my arms. The mix of anti‑mite cream and a cheeky antihistamine really does the trick most nights. If you catch ’em early you’ll dodge the whole drama.

Karen Richardson

1 Nov 2025

The immunologic cascade described in the article aligns with the classic Th2 pathway: allergen exposure leads to IL‑4 and IL‑13 secretion, which drives B‑cell class switching to IgE. Consequently, mast cells become sensitized and degranulate upon re‑exposure, releasing histamine and leukotrienes. This mechanism explains why antihistamines alone often provide incomplete relief in scabies‑associated dermatitis. A combined regimen of permethrin and a second‑generation antihistamine is therefore evidence‑based.

Victoria Guldenstern

18 Nov 2025

It is absolutely astounding how a creature no larger than a grain of sand can orchestrate a full blown theatrical production on the epidermis. The mite tunnels into the stratum corneum and leaves behind a trail of microscopic graffiti that the immune system interprets as an invitation to a party. IgE antibodies appear on the scene like over‑eager guests who never leave. Mast cells, ever the diligent bartenders, dump histamine the moment they sense the allergen. The result is itching that feels like a thousand tiny needles tapping in unison. And all this happens while the poor host is blissfully unaware that the infestation began weeks ago. The delayed onset is a masterstroke of biological irony. You go to bed thinking you just have a rash, only to awaken with a midnight symphony of scratches. The nocturnal surge in itching is not a coincidence; it is the circadian rhythm reminding the parasite that you are awake. Anti‑mite treatments such as permethrin act like a SWAT team, but they do not calm the angry crowd that has already gathered. Antihistamines are the peacekeepers that try to negotiate with the histamine‑fueled mob. Topical steroids provide the temporary ceasefire, but they can also weaken the skin’s barrier if overused. The paradox of needing both eradication and inflammation control is a classic case of medical yin and yang. In practice, you end up juggling creams, pills, and endless moisturizers like a circus performer. The bottom line is that scabies is not just a simple infestation; it is a complex immunological drama that demands a multidisciplinary script.

Jaime Torres

5 Dec 2025

Sounds like a drama you don’t need.

Wayne Adler

23 Dec 2025

I get it, the itch can drive anyone to the brink of madness and the thought of those mites crawling under your skin is enough to make you lose your cool. When I was dealing with a stubborn case I threw the permethrin on like a warzone and followed up with a heavy dose of benadryl to keep the scratching at bay. The combination knocked the infestation out and gave my skin a chance to heal without the constant burning. If you’re still suffering, don’t sit around waiting for a miracle – attack the problem with both meds and a good moisturizer that seals the barrier.

Lawrence Bergfeld

9 Jan 2026

Exactly! Apply permethrin, then antihistamine; keep skin hydrated; repeat if needed.

Sarah Kherbouche

27 Jan 2026

Honestly this whole scabies thing is just another excuse for lazy people to avoid basic hygiene. If you wash your sheets and don’t share socks you won’t end up with a rash that looks like a freak show. The “allergy” argument is just a smokescreen to get extra prescription meds they don’t need. Get your act together and treat the mite, stop whining about “immune responses”.

chioma uche

13 Feb 2026

True, the infestation spreads faster when folks ignore proper cleaning. Stronger measures and community awareness are the only ways to stop this pest.