Hypersomnia Disorders: Idiopathic Hypersomnia and Treatment

Imagine setting 17 alarms just to wake up for work - and still oversleeping three times in two months. That’s not a joke. It’s the daily reality for people living with idiopathic hypersomnia (IH). Unlike simply feeling tired after a bad night’s sleep, IH is a neurological disorder where your brain won’t let you stay awake, no matter how much rest you get. You might sleep 12 hours at night, take two-hour naps during the day, and still feel like you’ve been dragged through mud. And when you finally wake up? You’re disoriented, confused, and sometimes can’t even remember your own name for minutes at a time. This isn’t laziness. It’s a medical condition - one that’s often misdiagnosed for years.

What Is Idiopathic Hypersomnia?

Idiopathic hypersomnia is a rare neurological sleep disorder first identified in 1956. The word "idiopathic" means "of unknown cause." Unlike narcolepsy, which has clear biological markers like low orexin levels or cataplexy (sudden muscle weakness triggered by emotion), IH has no obvious trigger. Your body isn’t broken. Your brain just doesn’t know how to stay awake.

People with IH typically sleep 9 to 11 hours a night - sometimes more - and still feel exhausted. Their naps don’t refresh them. In fact, they often wake up feeling worse: groggy, irritable, and mentally foggy. This is called "sleep drunkenness," and it affects 36% to 66% of patients. Some describe it as being trapped between sleep and wakefulness, unable to fully come out of either state.

It usually starts in the teens or early 20s. The symptoms creep in slowly over weeks or months. At first, people think they’re just stressed or depressed. Many are told to "get more sleep" or "cut back on caffeine." But no amount of rest fixes it. That’s why diagnosis often takes 8 to 10 years. Patients see an average of 4.7 doctors before someone recognizes the pattern.

How Is It Different From Narcolepsy?

Most people confuse IH with narcolepsy. They’re both disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness, but they’re not the same.

Narcolepsy patients have sudden sleep attacks. They fall asleep without warning - mid-conversation, while driving, during a meeting. Their naps are short (10-20 minutes) and refreshing. Many also experience cataplexy - a sudden loss of muscle tone triggered by laughter or anger. Their nighttime sleep is often fragmented, with frequent awakenings.

People with IH don’t have sleep attacks. They don’t fall asleep suddenly. Instead, they’re constantly battling a heavy, unrelenting sleepiness. Their naps last over an hour and leave them more tired. They rarely have cataplexy. Their nighttime sleep is long but not broken. And here’s the kicker: the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), which is used to diagnose narcolepsy, often comes back normal for IH patients. That’s why many get missed.

One study found that 563 IH patients had significantly more brain fog and sleep inertia than narcolepsy patients. The longer their sleep duration, the worse their cognitive symptoms. This suggests IH isn’t just about sleep quantity - it’s about sleep quality and brain chemistry.

What’s Happening in the Brain?

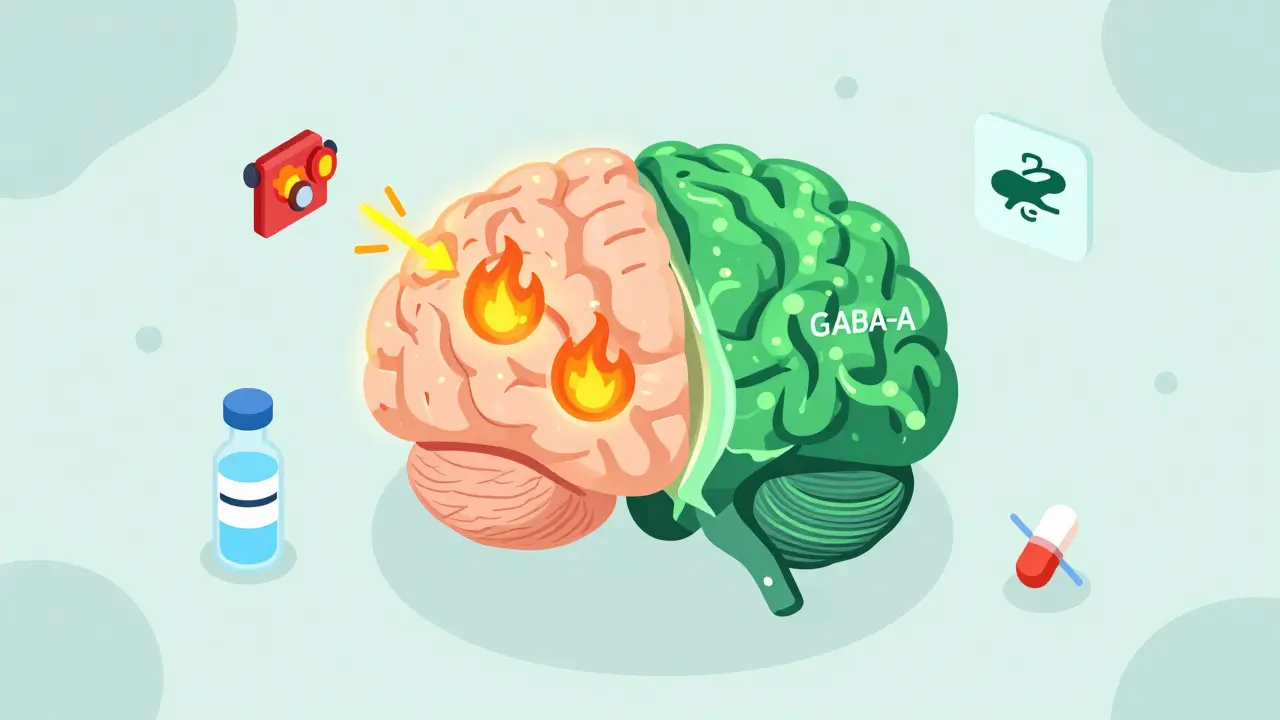

Research points to two major neurological factors in IH.

First, many patients have low levels of histamine - a brain chemical that keeps you alert. Think of histamine like a fire alarm for wakefulness. If it’s too quiet, your brain doesn’t get the signal to stay awake.

Second, a groundbreaking discovery in 2020 found that about half of IH patients have a substance in their spinal fluid that over-activates GABA-A receptors. GABA is a calming chemical in the brain. When it’s too active, it puts the brakes on wakefulness. This explains why stimulants like modafinil often don’t work well - they’re trying to fight an internal sedative.

Some studies also suggest problems with orexin, the brain’s natural wakefulness signal. In narcolepsy, orexin is missing. In IH, orexin might be present but not working right. These findings are why researchers now believe IH is not one condition, but a group of related disorders with different biological roots.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no blood test or MRI that confirms IH. Diagnosis is a process of elimination.

First, doctors rule out other causes: sleep apnea, restless legs, thyroid issues, depression, medication side effects, or substance use. Then they look at sleep patterns.

The gold standard is a two-night sleep study:

- Polysomnography (PSG): An overnight test that tracks brain waves, breathing, heart rate, and movement. It confirms you’re getting enough sleep - at least 6 hours - and that there’s no sleep apnea or other disorders.

- Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT): Done the next day, this measures how quickly you fall asleep during four or five nap opportunities. In IH, you fall asleep quickly (within 8 minutes on average), but you don’t enter REM sleep rapidly like narcolepsy patients do.

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) requires symptoms to last at least three months. The upcoming ICSD-4, expected in late 2024, will refine these criteria further.

But even with these tests, misdiagnosis is common. Many patients are labeled as having chronic fatigue syndrome or depression. The emotional toll is real. One survey found that 74% of IH patients met clinical criteria for depression - not because they were sad, but because they were exhausted, isolated, and felt like no one believed them.

Current Treatments

Treatment for IH is still limited - but it’s improving.

1. Xywav (calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium oxybate)

In August 2021, the FDA approved Xywav specifically for idiopathic hypersomnia. It’s the first and only drug approved for IH. Xywav is a liquid taken at night in two doses. It helps regulate sleep-wake cycles by acting on GABA-B receptors - the opposite of the GABA-A overactivity seen in IH. In clinical trials, patients saw a 63% drop in sleepiness scores. About 68% of users report moderate to significant improvement.

But it’s not perfect. Side effects include nausea, dizziness, headaches, and nighttime urination. It’s also expensive. Insurance companies often deny claims - 43% of initial requests are rejected. Patients typically need 2-3 appeals before getting coverage.

2. Modafinil and Armodafinil

These are stimulants originally designed for narcolepsy. About 42% of IH patients report some benefit. But many need higher doses over time, and side effects like anxiety, heart palpitations, and insomnia are common. For some, the trade-off isn’t worth it.

3. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Hypersomnia (CBT-H)

This isn’t your typical talk therapy. CBT-H is a 12-week structured program focused on sleep scheduling, managing naps, reducing caffeine, and coping with the emotional impact of chronic sleepiness. A 2020 study by Dr. Kiran Maski showed 45% of patients improved significantly after 12 weeks. When combined with medication, improvement jumps to 37%.

One patient from Sheffield told me: "I used to nap on the couch after lunch. Now I go for a walk. It doesn’t cure me - but it stops me from spiraling."

What Doesn’t Work

Many treatments for other sleep disorders fail in IH.

- Antidepressants: Often prescribed for fatigue, but they can worsen sleep inertia.

- Traditional stimulants (Adderall, Ritalin): May help briefly but lead to tolerance, anxiety, or rebound sleepiness.

- Over-the-counter caffeine: Useful in the morning, but using it after noon can disrupt nighttime sleep - making IH worse.

And while lifestyle changes like better sleep hygiene help with general tiredness, they don’t fix IH. You can’t sleep your way out of it.

Living With IH: Daily Challenges

The impact goes far beyond sleepiness.

- 62% of patients have lost jobs because they couldn’t stay awake.

- 78% have had near-miss car accidents.

- 41% forget basic safety tasks - like turning off the stove or locking doors.

- 87% say their condition severely limits their ability to work or study.

One Reddit user, "SleepyEngineer89," wrote: "I missed a deadline because I overslept. My boss said I wasn’t committed. I didn’t have the energy to explain."

Many patients avoid social events. They cancel plans. They stop dating. They feel like ghosts - present but not fully alive.

What’s Next?

The future of IH treatment is changing fast.

- New drugs: Five GABA-A modulators are in Phase 2 trials. Pitolisant, a histamine H3 receptor antagonist, showed a 47% response rate in early studies.

- Biomarkers: A 2023 study identified a unique pattern in spinal fluid that correctly diagnosed 89% of IH cases. This could lead to a simple blood test within the next few years.

- Orexin replacement: Still in preclinical stages, but if successful, it could be the first true cure.

- NIH funding: Increased from $1.2 million in 2018 to $8.7 million in 2023 - a 625% jump. More research means better answers.

The Hypersomnia Foundation’s 2023 Patient Registry, with over 2,100 participants, is now tracking long-term outcomes. By 2025, we should have clearer data on who responds to what treatment - and why.

Final Thoughts

Idiopathic hypersomnia isn’t just about being tired. It’s a neurological condition that steals time, relationships, careers, and peace of mind. But it’s not hopeless. With better diagnosis, targeted treatments, and growing awareness, people with IH are finally being heard.

If you or someone you know has been told they’re just "lazy" or "depressed" - and they sleep 10 hours a night and still can’t stay awake - it might be IH. Don’t give up. Keep pushing. Ask for a sleep specialist. Bring the data. You’re not alone.

Comments (13)

Maddi Barnes

20 Feb 2026

I can't believe people still think this is just 'being lazy' 😒 I had a cousin who slept 14 hours a night and still couldn't get out of bed. They told her to 'try harder' until she lost her job. Then she got diagnosed with IH. It's not a character flaw. It's a neurological glitch. And honestly? The fact that we're only now getting real treatments after decades of gaslighting is insane. 🤦♀️

Michaela Jorstad

21 Feb 2026

I'm so glad this post exists. My sister has IH, and I've watched her go from a brilliant engineer to someone who cancels every plan because she's too exhausted to even shower. The sleep drunkenness? Yeah. She once forgot her own phone number. And the worst part? People think she's 'just being dramatic.' No. She's fighting a war no one else can see. 💔

Davis teo

23 Feb 2026

I was diagnosed last year. I sleep 11 hours and still need a 3-hour nap. I once fell asleep in the middle of a Zoom meeting and woke up 45 minutes later with my face stuck to my keyboard. My boss said I needed to 'get my act together.' I didn't have the energy to explain that my brain is literally wired wrong. Now I work from home. And I still get judged. 😔

Jeremy Williams

24 Feb 2026

The histamine and GABA-A findings are fascinating. It makes sense that stimulants often fail-fighting an internal sedative is like trying to swim upstream with weights tied to your ankles. I wonder if future treatments will target the specific subtype rather than throwing drugs at the whole spectrum. Precision medicine could be a game-changer.

Scott Dunne

25 Feb 2026

This is just another example of American medical overreach. We pathologize normal human fatigue. People used to sleep more. Back in Ireland, we didn't have these 'disorders.' You worked hard, you rested. Now we have pharmaceutical companies inventing conditions so they can sell drugs. Xywav? $20,000 a year? Absurd.

Oana Iordachescu

26 Feb 2026

I don't trust this. The GABA-A finding? Coincidence. The spinal fluid? Could be contamination. The FDA approval? Corporate lobbying. The NIH funding spike? 2023? That's right after the pharmaceuticals got their lobbying budget renewed. I'm not saying IH isn't real-I'm saying the whole narrative is being manufactured. Who benefits? Who owns the patents? 🤔

Greg Scott

27 Feb 2026

I'm not a doctor, but I've known two people with this. One was a teacher. The other, a nurse. Both were brilliant. Both got written off as 'unreliable.' The real tragedy isn't the sleep-it's the stigma. People don't get that exhaustion can be neurological, not moral. You can't will yourself awake. And that's hard for people to accept.

aine power

28 Feb 2026

Xywav works. I'm on it. No more naps. No more sleep drunkenness. It’s not perfect. But it’s the first thing that didn’t make me feel like a zombie. The cost? Worth it. The stigma? Still sucks. But at least now I can function.

Irish Council

1 Mar 2026

The fact that MSLT comes back normal for IH is why I think it's a misdiagnosis. Maybe it's just severe depression masked as sleep disorder. Or maybe the test is flawed. Either way, I've seen too many people get labeled with this and then handed a $10k pill. Who's paying for the research? Who profits?

Ashley Paashuis

1 Mar 2026

I work in neurology and can confirm: IH is under-researched, under-diagnosed, and under-supported. The emotional toll is staggering. Patients often develop secondary depression because they’ve been told for years they’re 'faking it.' We need more sleep specialists trained to recognize the subtle signs-not just the textbook ones. And we need insurance reform. This shouldn't be a luxury.

Liam Crean

3 Mar 2026

I used to think I was just tired. Then I read this. I’ve been sleeping 10 hours, napping 2, still exhausted. I thought I was broken. Turns out I’m not alone. And the part about orexin not working right? That’s it. That’s the piece I didn’t know. I’m getting tested next week. Thank you for writing this.

madison winter

4 Mar 2026

It’s ironic. We live in a world obsessed with productivity, yet we ignore the biological limits of the human brain. IH exposes the lie that rest is optional. You can’t optimize sleep. You can’t hustle your way out of it. Some brains just don’t get the memo. And society? It punishes them for it.

John Cena

5 Mar 2026

I have a friend with IH. She once missed her own wedding rehearsal because she overslept. Her fiancé left her. Not because she didn’t love him. Because he didn’t understand. She’s still healing. I just wish more people knew this wasn’t laziness. It’s biology. And it’s real.