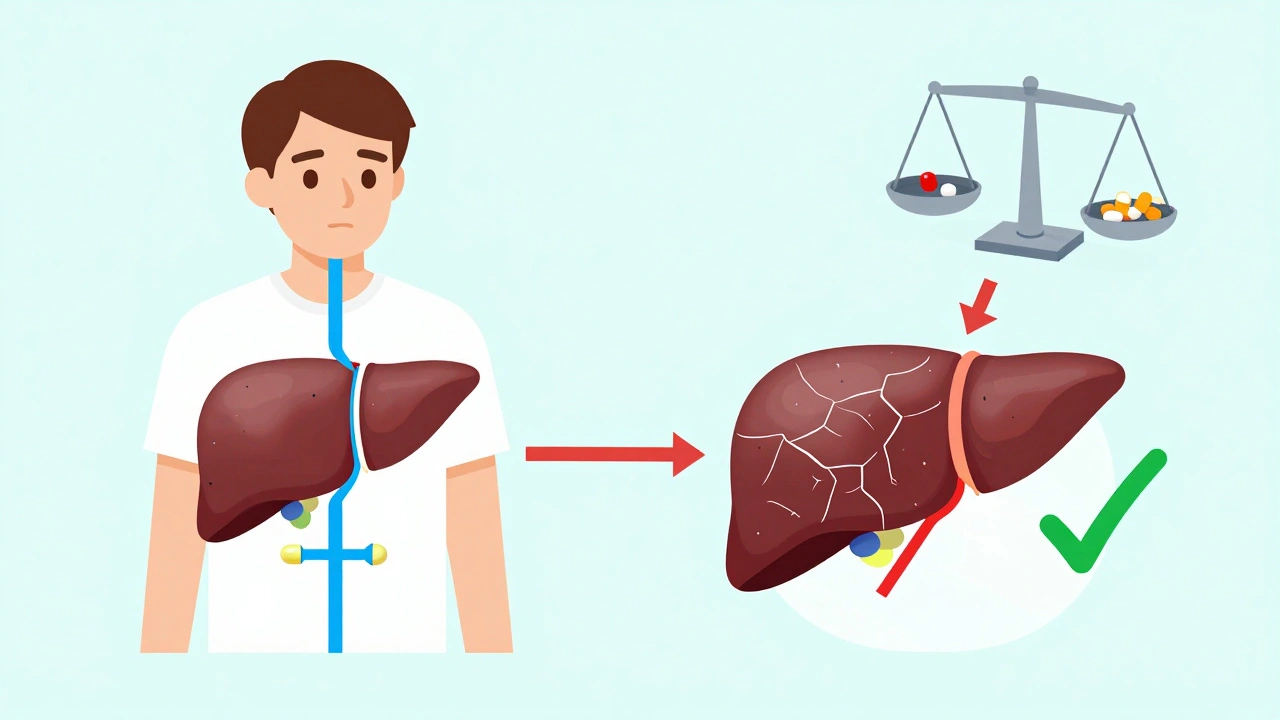

Opioids in Liver Disease: How Impaired Metabolism Increases Toxicity Risk

Opioid Dosing Calculator for Liver Disease

When someone has liver disease, taking opioids isn’t just riskier-it can be dangerous in ways most people don’t expect. The liver doesn’t just filter toxins; it breaks down drugs like morphine and oxycodone so they don’t build up in the body. But when the liver is damaged, that process slows down or stops. The result? Opioids stick around longer, at higher levels, and start causing side effects that can be life-threatening-even at normal doses.

How the Liver Normally Processes Opioids

The liver uses two main systems to handle opioids: cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These are the body’s way of turning drugs into water-soluble molecules that can be flushed out through urine or bile. For example, morphine is changed into two main metabolites: morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which helps with pain relief, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which doesn’t help with pain but can cause seizures and confusion. Oxycodone gets broken down mostly by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzymes into oxymorphone and other compounds. These processes are precise, and they rely on a healthy liver.

But in liver disease-whether from alcohol, fatty liver, or hepatitis-these systems don’t work the same way. CYP3A4 activity drops by up to 60% in advanced cirrhosis. Glucuronidation slows down too. That means opioids aren’t cleared fast enough. Instead of being eliminated, they pile up in the bloodstream. The half-life of oxycodone, which is normally around 3.5 hours, can stretch to over 14 hours in severe liver failure. That’s four times longer.

Why Morphine Is Especially Risky

Morphine is one of the most commonly prescribed opioids, but it’s also one of the worst choices for someone with liver disease. Why? Because its metabolism depends almost entirely on glucuronidation, which is among the first liver functions to fail. As liver damage worsens, the body can’t make enough M6G or clear M3G. Plasma levels of M3G rise, and that’s where the danger lies. Studies show that patients with cirrhosis have up to 5 times higher M3G concentrations than healthy people. That’s linked to a higher chance of delirium, myoclonus (involuntary muscle jerks), and even seizures.

Even more concerning: morphine’s pain-relieving metabolite, M6G, also builds up. So while you might think the patient is getting more pain relief, they’re actually getting more neurotoxicity. This is why experts recommend cutting morphine doses by at least 50% in early liver disease-and reducing both dose and frequency in advanced cases. Many clinicians now avoid morphine altogether in patients with Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis.

Oxycodone: A Double-Edged Sword

Oxycodone is often seen as a safer alternative, but that’s misleading. In liver disease, its clearance drops sharply. One study found that in patients with severe hepatic impairment, the maximum concentration of oxycodone in the blood increased by 40%, and the half-life jumped from 3.5 hours to an average of 14 hours-sometimes as long as 24 hours. That means even a single standard dose can linger for days.

Guidelines from the British National Formulary and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists say to start oxycodone at 30% to 50% of the usual dose in severe liver disease. Dosing intervals should be extended too-maybe every 8 to 12 hours instead of every 4 to 6. But here’s the catch: there’s no reliable way to predict how each person will metabolize it. Some patients with mild fatty liver might handle it fine. Others with hepatitis C and cirrhosis might overdose on a quarter of the normal dose. That’s why close monitoring is non-negotiable.

What About Methadone, Fentanyl, and Buprenorphine?

Methadone is metabolized by multiple CYP enzymes (CYP3A4, CYP2B6, CYP2D6), so it doesn’t rely on just one pathway. That sounds good-but there’s a problem. There are no clear dosing guidelines for liver disease. Some studies suggest methadone levels rise only slightly in cirrhosis, while others show dangerous accumulation. Without standardized protocols, many doctors avoid it.

Fentanyl is mostly cleared by the liver via CYP3A4, but it’s highly fat-soluble and has a short half-life. That makes it a candidate for transdermal patches, which bypass first-pass metabolism. Still, data is limited. One small study in patients with cirrhosis showed fentanyl clearance dropped by 30%, but the clinical impact wasn’t dramatic. Still, caution is advised.

Buprenorphine is different. It’s metabolized by CYP3A4 and glucuronidation, but it’s also highly protein-bound and has a very long half-life. Some studies suggest its clearance doesn’t change much in liver disease, and it’s less likely to cause respiratory depression than morphine or oxycodone. For that reason, it’s increasingly used in patients with liver disease-especially those with opioid use disorder. But again, there’s no consensus on dosing. Start low. Go slow.

How Opioids Can Worsen Liver Damage

It’s not just about drug buildup. Long-term opioid use can actually make liver disease worse. How? Through the gut-liver axis. Opioids slow down gut movement, which changes the balance of bacteria in the intestines. This imbalance, called dysbiosis, lets harmful bacteria and their toxins leak into the portal vein and reach the liver. That triggers inflammation, which speeds up fibrosis-the scarring that leads to cirrhosis.

Studies in mice with fatty liver disease showed that chronic morphine exposure increased liver inflammation markers by 70%. Human studies are still emerging, but early data suggests patients on long-term opioids for chronic pain have higher rates of liver fibrosis progression, especially if they have alcohol-related or metabolic liver disease.

What You Need to Know About Dosing

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule. But here’s what the evidence says:

- Morphine: Avoid in Child-Pugh B or C. If absolutely necessary, reduce dose by 50-75% and double dosing intervals.

- Oxycodone: Start at 30-50% of normal dose. Extend dosing to every 8-12 hours. Monitor closely for sedation and confusion.

- Buprenorphine: Consider first-line for chronic pain or addiction in liver disease. Start at 2-4 mg/day. Titrate slowly.

- Methadone: Use with extreme caution. No clear guidelines. If used, monitor QT interval and serum levels if available.

- Fentanyl patches: May be safer than oral opioids. Avoid in severe impairment until more data is available.

Always check liver function tests (ALT, AST, bilirubin, albumin, INR) before starting opioids. Use the Child-Pugh score to assess severity. And never assume a patient’s tolerance is the same as a healthy person’s. In liver disease, tolerance doesn’t protect you-it just delays the crash.

What’s Still Unknown

There are big gaps in our knowledge. We don’t know how opioids affect patients with early-stage NAFLD or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). We don’t have large-scale trials on buprenorphine dosing in cirrhosis. We don’t know if certain genetic variants in CYP enzymes make some people more vulnerable. And we still don’t have a clear way to measure opioid toxicity in real time for these patients.

One thing is certain: we’ve been prescribing opioids like they’re the same for everyone. They’re not. In liver disease, they’re a different drug entirely.

Bottom Line

If you or someone you care for has liver disease and needs pain relief, opioids aren’t off the table-but they need a whole new approach. Don’t just lower the dose. Change the drug. Change the timing. Monitor for signs of toxicity: drowsiness, confusion, slow breathing, or muscle twitching. Talk to a pain specialist or hepatologist. There are safer options out there, and avoiding opioids entirely might be the best choice for some.

The liver doesn’t heal overnight. But with careful management, you can manage pain without putting your liver-or your life-at further risk.

Can opioids cause liver damage on their own?

Opioids themselves aren’t directly toxic to the liver like acetaminophen or alcohol. But long-term use can worsen existing liver disease by disrupting the gut microbiome, increasing inflammation, and promoting fibrosis. This is especially true in fatty liver disease and alcohol-related liver disease.

Is morphine safe for people with cirrhosis?

No, morphine is generally not safe in cirrhosis, especially in moderate to severe cases. Its metabolites, particularly M3G, accumulate and can cause neurological side effects like seizures and confusion. Most guidelines recommend avoiding morphine in Child-Pugh B or C cirrhosis.

What’s the safest opioid for someone with liver disease?

Buprenorphine is currently considered the safest option for chronic pain in liver disease. It has lower respiratory depression risk, less accumulation, and doesn’t rely on a single metabolic pathway. Fentanyl patches may also be safer than oral opioids because they avoid first-pass metabolism. But all opioids require careful dosing and monitoring.

How do I know if an opioid is building up in my body?

Signs include extreme drowsiness, confusion, slurred speech, slow or shallow breathing, muscle twitching, or unexplained nausea. These can happen even at low doses in liver disease. If you notice any of these, stop the medication and contact your doctor immediately.

Should I avoid opioids completely if I have liver disease?

Not necessarily. Many people with liver disease need pain relief. The goal isn’t to avoid opioids entirely-it’s to use them smarter. Choose the right drug, start with a low dose, extend the time between doses, and monitor closely. Non-opioid options like acetaminophen (in low doses), gabapentin, or physical therapy should be tried first. But if opioids are needed, they can be used safely with the right precautions.

Comments (19)

Courtney Blake

10 Dec 2025

This is why America's opioid crisis is a medical farce. Doctors prescribe like they're handing out candy. Liver patients? They're just collateral damage. And nobody wants to admit we're poisoning people with 'safe' meds. 🤦♀️

Lisa Stringfellow

11 Dec 2025

I read this and just sighed. Another article that tells us what we already know but doesn't fix anything. Why do we even bother? The system won't change. People will still get prescribed morphine like it's Advil.

Kristi Pope

12 Dec 2025

Hey everyone - this is actually really important stuff. I've seen patients in my clinic go from mild pain to full-on delirium because someone didn't adjust the dose. It's not about fear, it's about care. Start low, go slow, listen to the body. We can do better. 💙

Aman deep

12 Dec 2025

in india we dont have much access to these drugs but i know someone with cirrhosis who got oxycodone and nearly died. doc said 'it should be fine'... turns out it wasnt. glad someone finally wrote this. we need more awareness in places like mine too 🙏

Eddie Bennett

14 Dec 2025

I'm not a doctor but I've watched my uncle go through this. They gave him morphine after surgery. He started twitching at 3am. Took 48 hours to figure out it was the drug. Scary stuff. This article nailed it. We need better protocols.

Sylvia Frenzel

15 Dec 2025

Morphine is a relic. We're still using 19th-century medicine on 21st-century livers. It's not just dangerous-it's arrogant. And don't get me started on how insurance won't cover buprenorphine because it's 'too expensive.'

Vivian Amadi

15 Dec 2025

Buprenorphine is NOT safer. It's just less obvious when it kills you. And don't even get me started on the 'guidelines.' They're written by pharma-funded academics who've never seen a cirrhotic patient in real life.

john damon

16 Dec 2025

bro i had a friend on fentanyl patches for back pain and his liver enzymes went through the roof. they said 'it's fine'... then he passed out at work. now he's on dialysis. 🤕💊

Taylor Dressler

18 Dec 2025

The data is clear: morphine should be avoided in Child-Pugh B/C, oxycodone requires 50% dose reduction, and buprenorphine is the best option with current evidence. Dosing must be individualized. Always monitor for CNS depression. This is standard of care, not opinion.

Jim Irish

19 Dec 2025

This is a well structured summary. However, the lack of standardized monitoring tools remains a critical gap. We measure INR and bilirubin, but not opioid metabolite levels. Until we can quantify toxicity in real time, we're flying blind.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

19 Dec 2025

I'm a nurse in a liver transplant unit. We see this every week. Patients come in with opioid toxicity, and the first question is always, 'Why did they give me this?' The answer? Because no one reads the guidelines. Or worse-they read them and ignore them.

Monica Evan

19 Dec 2025

my dad had hepatitis c and got prescribed oxycodone for arthritis. he was fine at first... then he started talking nonsense and couldn't walk straight. they thought it was dementia. turns out it was M3G buildup. took 3 days to detox. never again. please share this with your doc

Aidan Stacey

21 Dec 2025

This isn't just about liver disease. It's about how we treat chronic pain in America. We reach for pills before we reach for people. We need physical therapists, counselors, acupuncture, yoga-anything but opioids. And if we must use them? Treat them like dynamite.

Jean Claude de La Ronde

22 Dec 2025

Ah yes, the classic 'buprenorphine is safe' narrative. Because nothing says 'medical breakthrough' like a drug that costs $1000/month and requires weekly visits to a clinic that won't take your insurance. Thanks for the optimism, doc. I'll just keep taking ibuprofen and hoping my liver doesn't explode.

Mia Kingsley

22 Dec 2025

You say buprenorphine is safer? LOL. My cousin took it for 6 months and got addicted. Then she couldn't get off it. So now she's on methadone. So what? We just swapped one prison for another. This whole system is a scam.

Courtney Blake

22 Dec 2025

I see you're still peddling the 'buprenorphine is safe' fairy tale. Wake up. It's just another opioid with a nicer label. And don't pretend the system cares about liver patients. They care about billing codes. And if you're not a drug addict, you're not worth the paperwork.

Kristi Pope

22 Dec 2025

I hear you. And I'm not saying buprenorphine is perfect. But it's the *least worst* option we have right now. And it's saved lives. We need to push for better access, better monitoring, better training-not give up. The people who need this the most are the ones getting silenced. Let's keep talking.

Taylor Dressler

23 Dec 2025

Exactly. The goal isn't perfection. It's harm reduction. Buprenorphine has a ceiling effect-respiratory depression is far less likely. In cirrhosis, that matters. We don't have perfect tools, but we have better ones. Use them.

Katherine Liu-Bevan

25 Dec 2025

One sentence: If your doctor prescribes morphine to someone with cirrhosis, find a new doctor.