Crossover Trial Design: How Bioequivalence Studies Are Structured

When a generic drug company wants to prove their version of a medication works just like the brand-name version, they don’t test it on thousands of people. They use a smarter, quieter method - the crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick. It’s the backbone of how most generic drugs get approved worldwide. And if you’ve ever taken a generic version of your prescription, this is the method that made it possible.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Studies

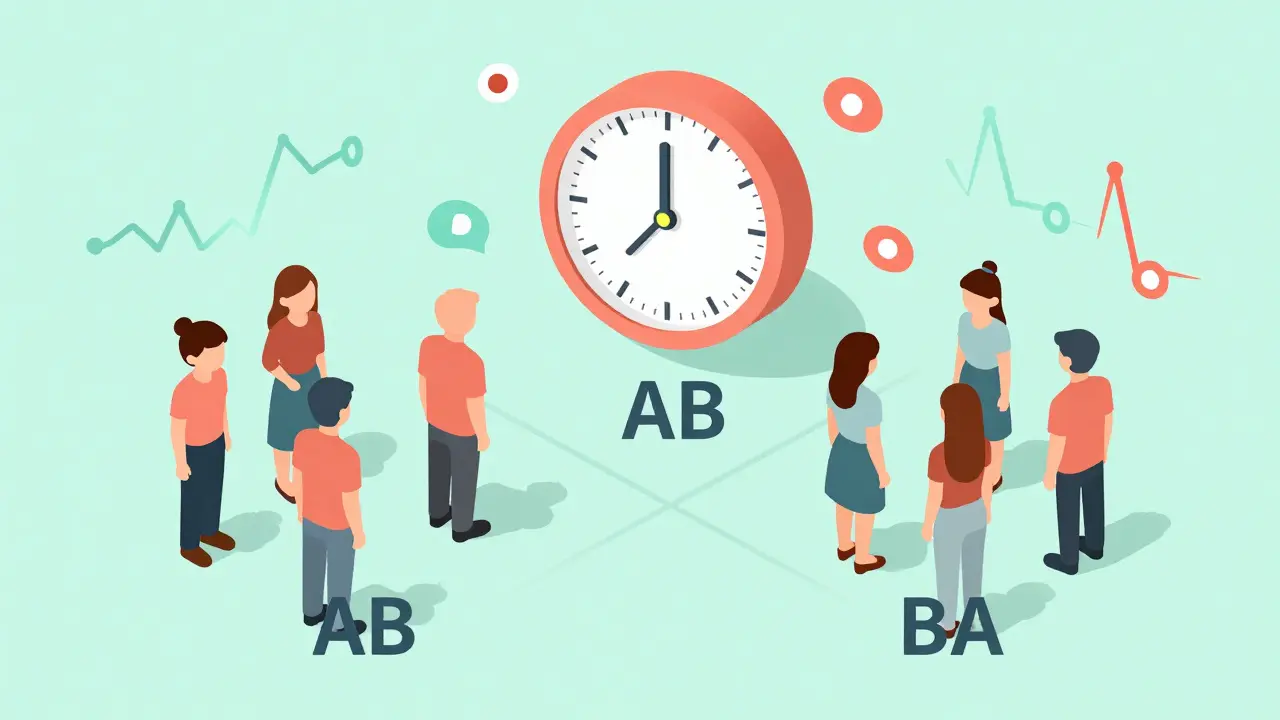

Imagine you’re trying to compare two different painkillers. You give one to 50 people and the other to 50 other people. But what if the first group is younger, healthier, or more active? Their results might look better - not because the drug is stronger, but because of who took it. That’s the problem with parallel-group trials. They rely on comparing different people, which introduces noise. Crossover designs fix that. Each person gets both drugs. First, they take Drug A, then after a break, they take Drug B. Because the same person is used for both, their age, metabolism, body weight, and even daily habits stay constant. The only thing changing is the drug. This cuts out a huge chunk of variability - the kind that makes studies need hundreds of participants just to see a real difference. In bioequivalence studies, this means you can get reliable results with as few as 12 to 24 people, instead of 70 or more in a parallel design. The U.S. FDA and the European Medicines Agency both say this is the preferred method. In fact, 89% of all generic drug approvals in the U.S. between 2022 and 2023 used crossover designs. That’s not a coincidence. It’s because it works.The Standard AB/BA Design

The most common crossover setup is called the 2×2 design - or AB/BA. Here’s how it works:- Half the participants get the test drug (T) first, then the reference drug (R) - that’s the AB sequence.

- The other half get the reference drug first, then the test drug - the BA sequence.

What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

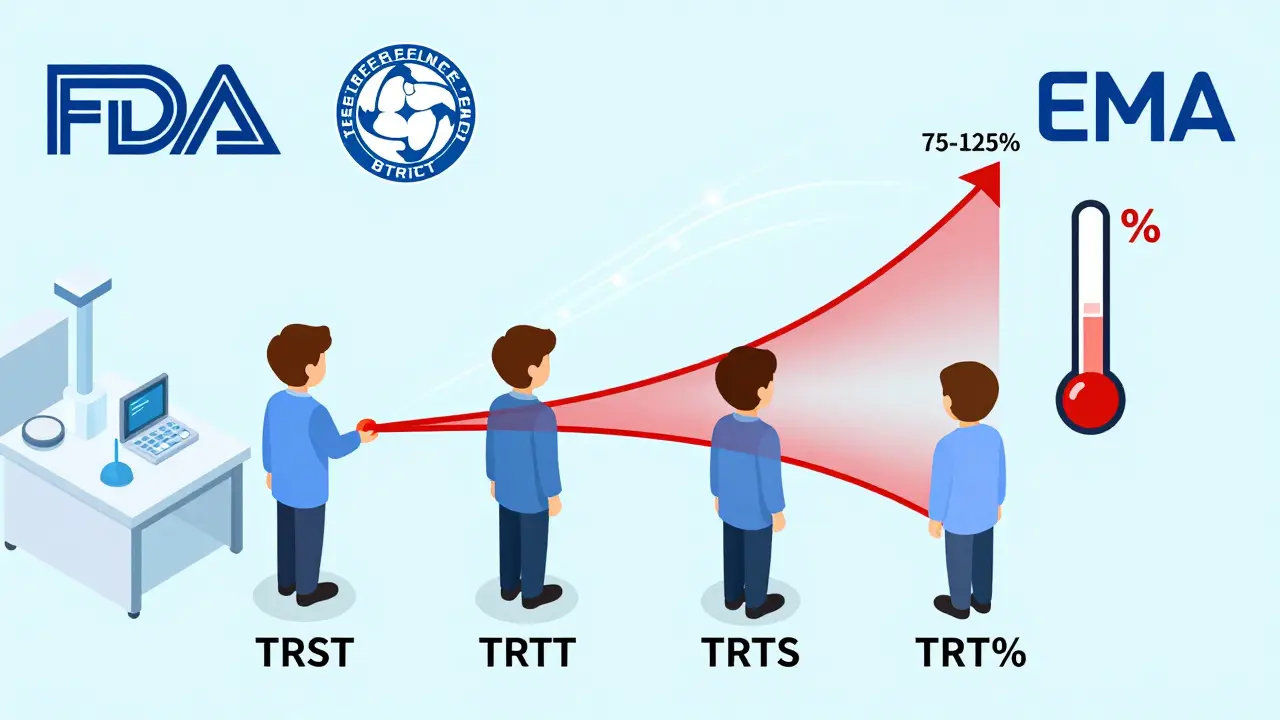

Not all drugs behave the same. Some - like certain blood thinners, epilepsy meds, or antibiotics - have what’s called high intra-subject variability. That means even the same person’s blood levels of the drug can swing wildly from one dose to the next. The coefficient of variation (CV) might hit 40% or more. For these, the standard AB/BA design doesn’t cut it. Why? Because the noise from the drug’s own behavior drowns out the signal you’re trying to measure: whether the generic matches the brand. The confidence interval for bioequivalence might fall outside the 80-125% range, even if the drugs are identical. That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of two doses per person, you give four. There are two main types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Each person gets the test drug once and the reference drug twice.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Each person gets both drugs twice.

How They Analyze the Data

It’s not enough to just give the drugs and measure blood levels. You need to prove the difference isn’t random. That’s where statistics come in. The standard analysis uses a linear mixed-effects model. The model checks for three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order (AB vs. BA) affect the result? If so, maybe the washout wasn’t long enough.

- Period effect: Did something change between the first and second period - like diet, stress, or seasonal illness?

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the test and reference drug?

Real-World Wins and Failures

In 2022, a team testing a generic warfarin used a 2×2 crossover and saved $287,000 and eight weeks compared to a parallel design. They only needed 24 participants. The study passed. Another team, testing a highly variable antibiotic, used the same 2×2 design. Their intra-subject CV was 42%. They didn’t adjust for it. The washout was based on literature, not their own pilot data. Residual drug showed up in the second period. The study failed. They had to restart with a 4-period replicate design - at an extra cost of $195,000. This isn’t rare. About 15% of rejected bioequivalence submissions in 2018 had washout issues. The problem isn’t the design. It’s the execution.

When Crossover Doesn’t Work

Crossover designs are powerful, but they’re not universal. They fail when:- The drug’s half-life is too long (over two weeks).

- The condition being treated changes over time - like a progressive disease.

- The drug causes permanent effects - like a vaccine or a drug that alters immune response.

- There’s a high risk of carryover effects, and you can’t prove the washout worked.

The Future of Crossover Designs

The trend is clear: more replicate designs. In 2015, only 12% of highly variable drug approvals used RSABE. By 2022, that jumped to 47%. And it’s still rising. The industry is moving toward adaptive designs too - where you start with a small group, check the data, and decide whether to add more participants. That’s what 23% of FDA submissions did in 2022, up from 8% in 2018. New guidance from the FDA in 2023 even allows 3-period designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs - like those used for epilepsy or thyroid disorders - where tiny differences can be dangerous. The EMA’s 2024 update will likely require full replicate designs for all highly variable drugs. What’s next? Digital monitoring. Wearables that track drug levels in real time could one day eliminate the need for washout periods entirely. But that’s still years away. For now, the crossover design remains the gold standard. It’s efficient, scientifically sound, and trusted by regulators worldwide.What You Need to Remember

- Crossover designs cut sample size by up to 80% compared to parallel studies.

- Washout periods must exceed five half-lives - and you must prove it.

- For drugs with high variability (CV >30%), use a replicate design - not the standard 2×2.

- Statistical analysis must test for sequence, period, and treatment effects.

- RSABE allows wider bioequivalence limits for highly variable drugs - it’s not cheating, it’s science.

What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control. This removes inter-subject variability - differences between people like age, weight, or metabolism - and focuses only on the drug’s effect. This dramatically increases statistical power, allowing researchers to use far fewer participants than in parallel-group studies.

Why is the washout period so important in crossover trials?

The washout period ensures that the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If any of the first drug remains, it can interfere with the results of the second period - this is called a carryover effect. Regulatory agencies require washout periods of at least five half-lives of the drug, and studies must provide data proving concentrations fell below the lower limit of quantification.

When should a replicate crossover design be used?

A replicate design (TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) should be used when the intra-subject coefficient of variation for the reference drug exceeds 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance limits based on how variable the original drug is - making it fairer and more accurate for highly variable drugs like warfarin or phenytoin.

What are the most common mistakes in crossover bioequivalence studies?

The most common mistakes are: inadequate washout periods (leading to carryover), failing to test for sequence effects in statistical analysis, using the wrong statistical model, and not validating the washout with actual pharmacokinetic data. Poor randomization - assigning treatments instead of sequences - is also a frequent flaw.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (over two weeks), drugs that cause permanent physiological changes (like vaccines), or conditions that progress over time. In these cases, parallel-group designs are required, even though they need larger sample sizes and cost more.

Comments (14)

Aysha Siera

17 Jan 2026

They say it's science but I've seen the files. The FDA and Big Pharma are in bed together. They use these 'crossover' studies to hide the truth - generics are never the same. The body knows. You feel it. That weird nausea after switching? That's the ghost of the original drug haunting your bloodstream.

Tyler Myers

17 Jan 2026

Look, I've reviewed 37 bioequivalence protocols in my career. The crossover design is the only thing keeping generic drug approval from collapsing under its own weight. You want to compare apples to apples? Use the same apple. That's not conspiracy - it's basic experimental design. Stop listening to TikTok pharmacists.

Stacey Marsengill

18 Jan 2026

I used to take generic lisinopril. Then I switched back to brand. I cried. Not because I'm dramatic - because my blood pressure didn't spike for the first time in 3 years. They told me it was placebo. But my body remembers. And so do I.

rachel bellet

19 Jan 2026

The statistical model assumes normality, homoscedasticity, and no carryover - all of which are violated in real-world populations. The FDA's acceptance of RSABE is a statistical band-aid on a systemic failure. The 80-125% range was never meant to be scaled. This isn't precision - it's regulatory capitulation.

Pat Dean

21 Jan 2026

America invented this system. Now the EU is stealing it. And for what? So some foreign lab can slap a label on a pill and call it 'equivalent'? We built the FDA to protect Americans - not to greenlight foreign generics that barely pass a 24-person test in a basement lab in Bangalore.

Robert Davis

21 Jan 2026

I get why people are skeptical. But if you think the system is rigged, you're ignoring the data. The 90% CI for AUC and Cmax is the gold standard. It's not perfect. But it's the best we've got. And yes - I've seen the SAS code. It's clean.

Max Sinclair

23 Jan 2026

This is actually one of the most elegant applications of experimental design in medicine. Reducing variability by using each person as their own control? Brilliant. And the washout period? Non-negotiable. If you're skipping it, you're not cutting corners - you're risking lives.

Praseetha Pn

23 Jan 2026

You think they test the drugs? Nah. They test the paperwork. I worked at a lab in Mumbai - we'd just re-label the same batch as 'test' and 'reference' and call it a day. The washout? They just wait until the lab techs finish their chai. The CV? Made up. RSABE? Just a fancy way to say 'trust us'.

Chuck Dickson

25 Jan 2026

Hey everyone - if you're into this stuff, check out the FDA's 2023 guidance on 3-period designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs. It's a game-changer. And for those of you scared of RSABE? It's not a loophole - it's math that finally caught up with biology. Keep learning. You got this 💪

Robert Cassidy

25 Jan 2026

The crossover design is the last gasp of Cartesian reductionism in medicine. We reduce the human body to a variable, a sequence, a pharmacokinetic curve - and call it progress. But the soul? The spirit? The chaos of being human? It doesn't fit in a 2×2 table. And maybe that's why we keep failing.

Naomi Keyes

27 Jan 2026

The statistical analysis, as outlined, requires a linear mixed-effects model - which, by definition, assumes that random effects are normally distributed. However, in populations with high intra-subject variability - particularly in elderly or comorbid patients - this assumption is frequently violated. Furthermore, the use of PROC MIXED or WinNonlin is not standardized across sponsors, leading to inter-laboratory discrepancies - a critical flaw in regulatory acceptance.

Dayanara Villafuerte

29 Jan 2026

So… you’re telling me I’ve been taking the same pill for 5 years, just with a different label? 😳🤯 And they say it’s ‘equivalent’? I’m not mad… I’m just disappointed. 🤷♀️💊 #GenericTruth #PharmaWhisperer

Andrew Qu

30 Jan 2026

If you're developing a generic and you're using a 2x2 design for a drug with CV >30%, you're setting yourself up for failure. I've seen it happen too many times. Take the extra time. Do the replicate. It's cheaper in the long run. Trust me - I've been there.

kenneth pillet

1 Feb 2026

washout period needs to be longer than 5 half lives not just 'at least' - and you gotta prove it with actual pk data not just 'we think it's enough'