Bioavailability Studies for Generics: What They Test and Why

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how does the FDA make sure it does? The answer lies in bioavailability studies - the quiet, rigorous science behind every generic drug approved in the U.S.

What Bioavailability Actually Means

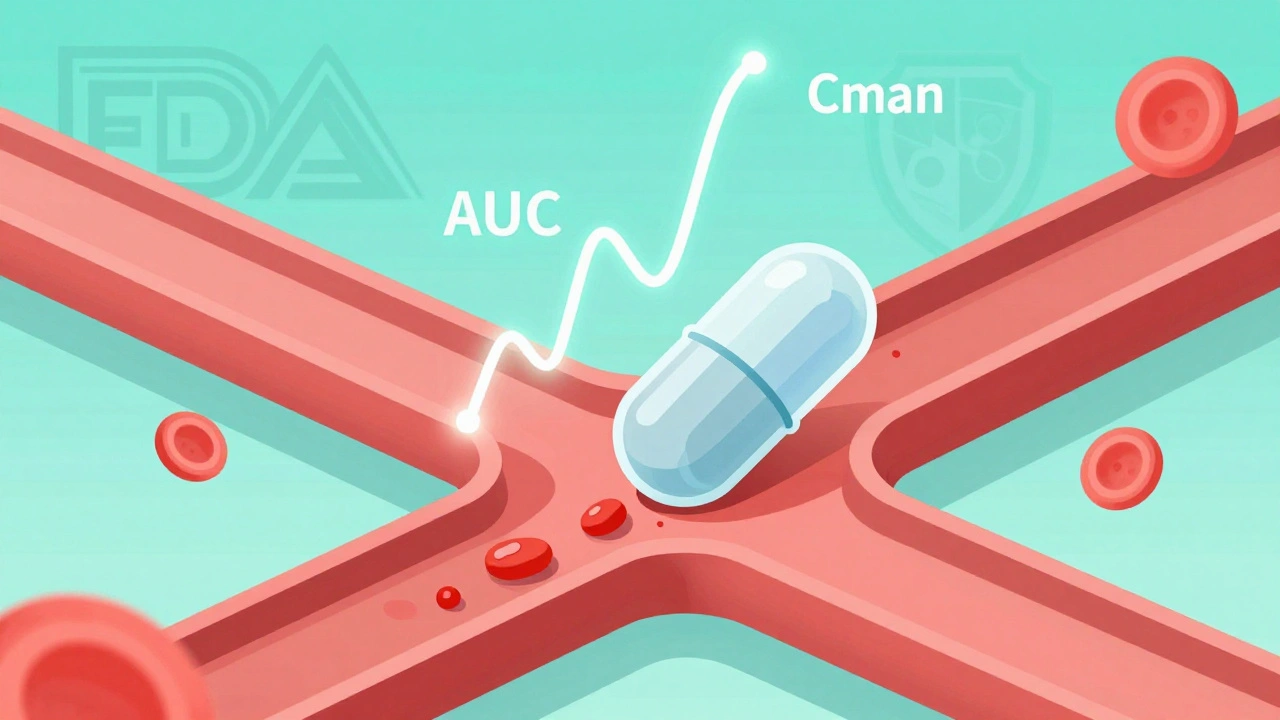

Bioavailability isn’t just about whether a drug gets into your body. It’s about how fast and how much of it gets there. The FDA defines it precisely: the rate and extent to which the active ingredient is absorbed into your bloodstream and reaches the site where it needs to work. Two numbers tell the whole story: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (Maximum Concentration).AUC measures total exposure - how much drug your body has over time. Think of it like the total rainfall in a day. Cmax is the peak - the highest point your blood drug level reaches, like the heaviest downpour. Together, they show if the generic matches the brand-name drug in how it behaves inside you.

For example, if a brand-name drug gives you an AUC of 100 units and the generic gives 95, that’s fine - as long as it’s within the allowed range. But if it’s 70? That’s a problem. The system isn’t just checking if the pill looks the same. It’s checking if your body treats it the same way.

How Bioequivalence Is Proven

Bioequivalence is the goal. It means the generic and brand-name versions are practically identical in how they’re absorbed. To prove it, companies run controlled studies in healthy volunteers. Usually, 24 to 36 people take both the generic and the brand-name version, in random order, with a break in between to clear the first dose.Researchers take blood samples - often 12 to 18 times over 24 to 72 hours - to track how the drug moves through the body. They calculate AUC and Cmax for each version. Then they compare them. The rule? The 90% confidence interval for the ratio of these values must fall between 80% and 125%. That’s not arbitrary. It’s based on decades of clinical data showing that differences smaller than 20% rarely affect how well a drug works.

Take a real case: One generic had an AUC ratio of 1.16 - meaning it delivered 16% more drug than the brand. At first glance, that seems fine. But the upper limit of the confidence interval hit 1.30. That broke the 125% rule. The product was rejected. Even if the average looks good, the range has to be tight. This isn’t about perfection - it’s about safety.

Why This Matters for Patients

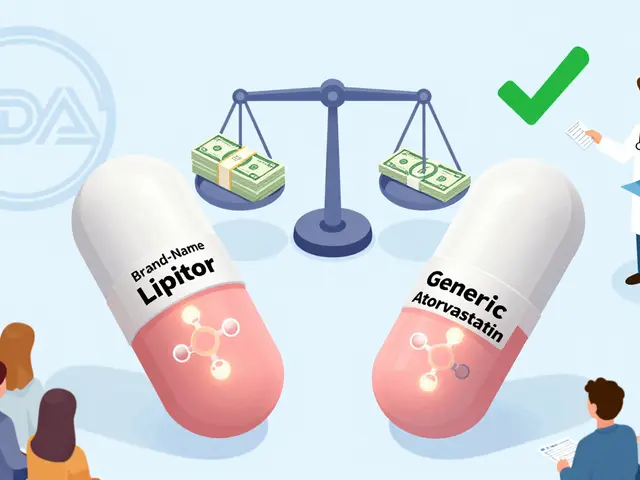

You might wonder: why not just test if the drug cures the disease? Why go through all this blood sampling? The answer is efficiency and safety.Before 1984, every generic needed full clinical trials - expensive, slow, and unnecessary. The Hatch-Waxman Act changed that. It let the FDA approve generics based on bioequivalence, saving billions and making medicines affordable. Today, 97% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics. They account for 89% of pills taken, but only 26% of drug spending.

Studies show 90% of patients can’t tell the difference between brand and generic. But there are exceptions. Some patients with epilepsy report seizures after switching. The Epilepsy Foundation logged 187 cases between 2020 and 2023. The FDA investigated and found only 12 - about 6% - might be linked to bioequivalence issues. Most were due to missed doses or other factors.

For drugs like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine - where small changes can have big effects - the rules are tighter. The acceptable range narrows to 90-111%. Some states even require doctors to approve substitutions. These aren’t failures of the system. They’re smart adjustments for high-risk drugs.

What Happens When the System Gets Stretched

Not all drugs are created equal. Simple tablets? Easy to test. Extended-release capsules? Harder. Inhalers? Even harder. Topical creams? Nearly impossible to measure through blood.For complex products, the FDA has adapted. For highly variable drugs - like tacrolimus - where people’s bodies absorb the drug differently from day to day, the agency now uses scaled bioequivalence. If the brand’s variability is high, the acceptance range widens to 75-133%. This prevents good generics from being rejected just because of natural body differences.

For inhalers and gels, they use other methods: measuring drug levels in the lungs, or tracking skin whitening as a sign of absorption. These aren’t perfect, but they’re the best tools available.

And now, AI is stepping in. In 2023, the FDA partnered with MIT to train machine learning models on 150 drug compounds. The models predicted AUC ratios with 87% accuracy - using only formulation data, no human trials. That could cut study times and costs in the future.

What’s Tested Beyond AUC and Cmax

AUC and Cmax are the stars, but they’re not alone. Tmax - the time it takes to reach peak concentration - also matters. If a generic hits peak levels much faster or slower, it could change how you feel. For example, a painkiller that kicks in 90 minutes later isn’t as useful.For some drugs, they even test urine excretion - how much drug your body gets rid of over time. For others, they look at how the drug affects your body’s response - like blood pressure changes or seizure thresholds.

And then there’s the BCS waiver. If a drug is highly soluble and highly absorbable (Class 1), and the generic uses the same inactive ingredients, the FDA may skip human studies entirely. That’s rare, but it happens. It’s a win for speed and cost - without sacrificing safety.

The Real-World Impact

Bioequivalence studies aren’t just lab exercises. They’re the reason you can fill a 30-day prescription for metformin for $4 instead of $300. They’re why heart patients can afford their blood thinners, and diabetics can keep their insulin.But they’re not flawless. Some pharmacists and doctors report rare cases where patients have side effects after switching - palpitations, dizziness, or mood changes. In one cardiologist’s practice, three out of 3,000 patients had issues with amlodipine. All reversed when they switched back.

That’s why the system includes checks: the 90% confidence interval isn’t just a number. It’s a safety net. It ensures that even if the average looks good, the worst-case difference is still unlikely to be harmful.

The FDA has approved over 15,000 generic drugs since 1984. Only a handful have ever been pulled for safety reasons - and almost none because of failed bioequivalence. The system works. It’s not perfect, but it’s proven.

What’s Next

The future of bioequivalence is smarter, not just bigger. The FDA is moving toward model-informed drug development - using computer simulations to predict how a drug will behave. If a formulation matches known patterns, it might not need a full human study.That’s good news for patients. Faster approvals mean more affordable options sooner. But it also means regulators need better data, better models, and better oversight. The goal isn’t to cut corners. It’s to cut waste - without cutting safety.

For now, if you take a generic, you can trust it. The science behind it is solid. The standards are strict. And the system has kept millions of people healthy - at a fraction of the cost.

Do bioavailability studies prove a generic drug works as well as the brand?

Yes. Bioavailability studies measure how much of the drug enters your bloodstream and how quickly. The FDA assumes that if two drugs have the same rate and extent of absorption, they’ll have the same clinical effect. This assumption has held true for over 30 years across thousands of drugs. For most medications, bioequivalence is a reliable predictor of therapeutic equivalence.

Why is the acceptance range 80-125%? Isn’t that too wide?

It’s not wide - it’s carefully calibrated. A 20% difference in bioavailability is generally not clinically meaningful for most drugs. Studies show patients don’t notice differences within this range. The 90% confidence interval ensures that even the upper and lower bounds are unlikely to exceed 25% in either direction. For high-risk drugs like warfarin, the range is tighter: 90-111%.

Can a generic pass bioequivalence but still cause side effects?

Rarely, but yes. Bioequivalence ensures the drug behaves the same in most people. But individual biology varies. Some people are extra sensitive to small changes in timing or inactive ingredients. For example, a few patients switching from brand to generic amlodipine reported palpitations - all resolved when they switched back. These cases are uncommon - under 0.1% - but they’re why pharmacists and doctors monitor patients after a switch.

Are bioequivalence studies the same worldwide?

For most standard oral tablets, yes. The FDA, EMA (Europe), and PMDA (Japan) follow nearly identical guidelines under ICH standards. The 80-125% range is global. But for complex products - like inhalers, gels, or extended-release capsules - each agency may have specific requirements. Some countries require additional testing or different study designs.

Why do some generics cost less than others if they’re all bioequivalent?

Cost differences come from manufacturing, packaging, and market competition - not quality. All approved generics must meet the same bioequivalence standards. A cheaper version might use simpler packaging, have lower marketing costs, or be made by a company with lower overhead. But the active ingredient and absorption profile are identical. Price doesn’t reflect effectiveness.

Can I trust a generic if it’s made overseas?

Yes. The FDA inspects all manufacturing facilities - whether in the U.S., India, China, or elsewhere - before approving a generic. Facilities must follow the same quality standards as U.S. plants. The agency conducts over 3,000 inspections annually. A drug’s origin doesn’t determine its safety. What matters is whether it passed bioequivalence testing and met FDA quality controls.

What to Do If You Notice a Change After Switching

If you’ve switched to a generic and feel different - whether it’s dizziness, fatigue, or worsening symptoms - don’t assume it’s all in your head. Talk to your doctor. Keep a log: when you switched, what symptoms appeared, and when they improved or worsened. Your doctor can check if it’s a known issue with that generic or if you need to switch back.Most people won’t notice a difference. But if you’re one of the few who do, you’re not alone - and there’s a path forward. The system is designed to catch problems before they become widespread. Your feedback helps make it better.

Comments (15)

Harriet Wollaston

13 Dec 2025

Love this breakdown. I used to worry about generics until my dad switched to generic metformin and saved $200 a month. He’s been fine for 3 years now. Science > marketing.

Lauren Scrima

15 Dec 2025

Oh, so you mean the FDA doesn’t just let any random Chinese factory slap a label on a pill and call it ‘equivalent’? Shocking. 😏

Constantine Vigderman

16 Dec 2025

This is wild. I had no idea they did blood draws 18 times over 72 hours 😳 I thought generics were just cheaper copies. Now I’m kinda impressed. 🤓

Ronan Lansbury

17 Dec 2025

Of course they say it’s safe. Who do you think funds the studies? Big Pharma’s shadow subsidiaries. The 80-125% range? That’s a loophole designed to let inferior drugs slip through so you keep buying. They don’t care if you get a 15% weaker dose - as long as you don’t die immediately.

And don’t get me started on the ‘BCS waiver.’ That’s just corporate laziness dressed up as science. If they can skip human trials, why not skip the whole damn process?

My cousin’s epilepsy spiked after switching. They blamed ‘missed doses.’ But the generic? Different filler. Corn starch instead of lactose. He’s allergic. No one tested that. No one cares.

The FDA’s not a watchdog. It’s a revolving door for ex-pharma execs. You think they’d reject a product that’s 16% stronger? Please. They’d approve it and call it ‘enhanced bioavailability.’

They’re not protecting you. They’re protecting profits. And you’re the sucker who believes the hype.

nina nakamura

19 Dec 2025

80-125%? That’s not science. That’s a corporate compromise. If your drug varies more than 10% in real-world use, you’re not bioequivalent - you’re a gamble. And you’re telling me this is acceptable for anticoagulants? No wonder people die.

Also, ‘rare cases’? 187 reported seizures? That’s not rare. That’s negligence dressed up as statistics.

Casey Mellish

20 Dec 2025

As an Aussie, I’m glad to see the FDA’s standards align with ours. We use the same 80-125% range - and for good reason. The science is solid. I’ve worked in pharmacy for 12 years. Generics save lives. End of story.

Yatendra S

20 Dec 2025

Life is like a drug… sometimes you need the brand name to feel whole. But the universe gives us generics to teach us humility. 🌱✨

Karen Mccullouch

22 Dec 2025

Why are we letting foreign factories make our medicine? This is a national security issue. If China controls our blood levels, what’s next? Our insulin? Our heart pills? We need Made in America generics. Or none at all.

Richard Ayres

22 Dec 2025

Thank you for this clear, well-researched explanation. It’s refreshing to see science communicated without sensationalism. The 90% confidence interval isn’t a flaw - it’s a safeguard. And the shift toward model-informed development? That’s the future.

sharon soila

22 Dec 2025

You’re not just taking a pill. You’re trusting a system that’s been tested for 40 years. And it works. Millions of people are alive because of this. Be grateful.

Emma Sbarge

24 Dec 2025

So you’re saying a pill made in India is just as good as one made in New Jersey? I don’t buy it. Our drugs should be made by Americans. Period.

Sheldon Bird

26 Dec 2025

So many people stress over generics… but honestly? If your body reacts badly, just switch back. Your doc will help. No need to panic. The system’s got your back. 💪❤️

Cole Newman

26 Dec 2025

Wait so you’re telling me I can’t tell the difference between brand and generic? That’s kinda depressing. I thought I had a sixth sense for meds. Guess I’m just a sucker for branding.

Donna Hammond

27 Dec 2025

One thing people forget: bioequivalence doesn’t just mean the same absorption - it means the same safety profile. The FDA doesn’t approve anything unless it’s been tested for toxicity, purity, and stability too. Generics aren’t ‘cheap’ - they’re efficient.

And yes, the inspections are brutal. I’ve seen the reports. The FDA doesn’t play around.

Tommy Watson

28 Dec 2025

bro why are we even talking about this… i just want my pills to not cost $300. if it works, it works. stop overthinking. 🤷♂️