Lung Cancer Screening for Smokers and the Rise of Targeted Therapies

Every year, over 130,000 people in the U.S. die from lung cancer. That’s more than colon, breast, and prostate cancer combined. The scary part? Most of these deaths happen because the cancer was found too late. But there’s a real chance to change that-especially for smokers and former smokers. Today, screening and targeted therapies are changing the game. It’s not science fiction. It’s happening right now.

Who Should Be Screened? It’s Not Just Who You Think

If you’ve smoked a pack a day for 20 years-or two packs a day for 10 years-you’re in the high-risk group. That’s called a 20 pack-year history. It doesn’t matter if you quit 10 years ago, 15 years ago, or even 20 years ago. The risk doesn’t just vanish when you stop smoking. A 2022 study in JAMA Oncology found people who quit 15 to 30 years ago still had 2.5 times the risk of lung cancer compared to people who never smoked.

The guidelines changed in 2023. The American Cancer Society now recommends annual low-dose CT (LDCT) scans for anyone aged 50 to 80 with a 20+ pack-year history, no matter when they quit. That’s a big shift. Before, most insurers and even Medicare only covered screening if you quit within the last 15 years. Now, that cutoff is gone. That means millions more people qualify.

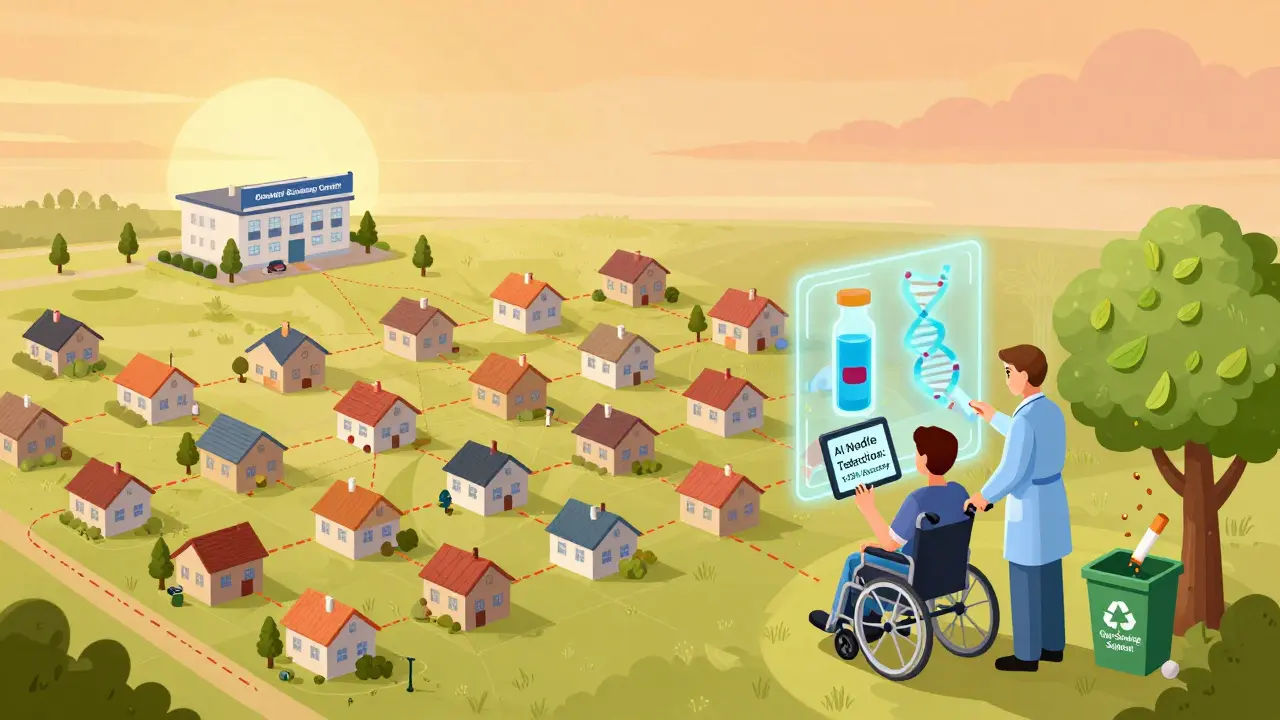

But here’s the problem: only about 18% of eligible people are actually getting screened. Why? Many doctors still don’t know the updated rules. A 2022 survey found 42% of primary care providers weren’t aware of the 2021 USPSTF changes. Patients don’t know they’re eligible. And in rural areas, there are 67% fewer screening centers than in cities. If you live in a small town, getting a scan might mean driving two hours.

How LDCT Screening Actually Works

LDCT isn’t your regular chest X-ray. It’s a fast, painless scan that uses 70-80% less radiation than a standard CT. You lie on a table, hold your breath for 10 seconds, and that’s it. No needles, no prep. The machine takes hundreds of detailed images of your lungs.

The goal? Find tumors when they’re smaller than a grape. At that stage, the five-year survival rate jumps to 59%. If it’s found after spreading? That drops to 6%. That’s the difference between living and dying.

But LDCT isn’t perfect. About 96% of positive results turn out to be false alarms-a scar, a benign nodule, inflammation. That means extra scans, biopsies, anxiety. That’s why screening should only happen at ACR-accredited centers. These facilities follow strict protocols: they use the right machine settings (120 kVp, 30-50 mAs), have radiologists trained in lung nodules, and have systems to track results over time.

And it’s not just about the scan. You need a shared decision-making visit first. That’s a 15-minute chat with your doctor about risks, benefits, and whether you’re healthy enough to handle surgery if something is found. If you have heart failure, severe COPD, or other life-limiting conditions, screening might do more harm than good.

Why So Few People Are Getting Screened

Let’s be honest: the system is broken. Even though Medicare covers LDCT for people 50-77 with a 20-pack-year history, many private insurers still use the old 30-pack-year rule. That means some people pay out of pocket-$300 to $500 per scan.

Then there’s access. The U.S. has only about 2,800 ACR-accredited screening centers for a population of over 14 million eligible people. That’s one center for every 5,000 eligible individuals. In rural counties, it’s worse. Some areas have none.

And then there’s awareness. A 2022 American Lung Association report found Black Americans eligible for screening are 35% less likely to get tested than white Americans. Rural residents? 42% less likely. Language barriers, mistrust in the system, lack of transportation-all play a role.

But there’s hope. Electronic health record alerts that pop up when a patient hits the screening criteria? They boost screening rates by 32%. Patient navigators who help schedule appointments, arrange rides, explain results? They increase adherence by 27%. And when smoking cessation programs are built into screening centers? That’s where real change happens. Seventy percent of current smokers say they want to quit-but only 30% get help. That needs to change.

Targeted Therapy: When Early Detection Meets Precision Medicine

Here’s where things get exciting. Screening doesn’t just catch cancer early. It catches cancer that can be treated with targeted drugs.

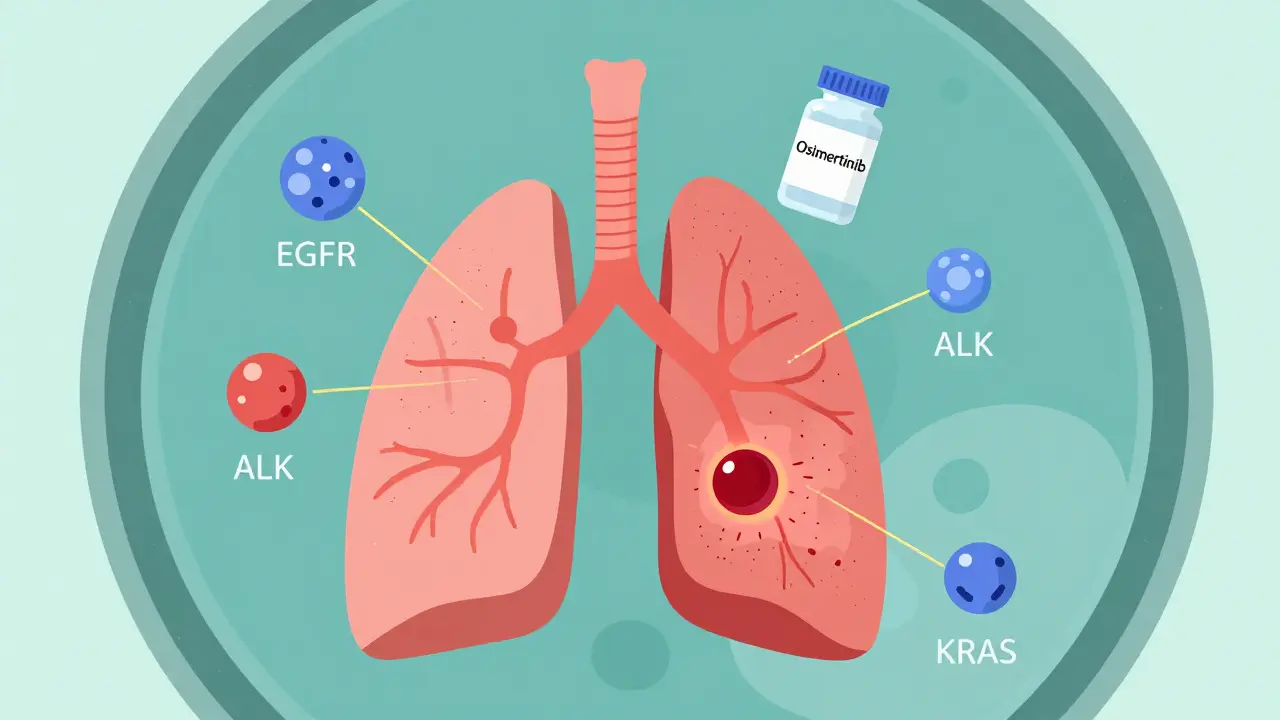

For decades, lung cancer was treated like one disease: chemotherapy, radiation, surgery. Now we know it’s dozens of diseases-each driven by different gene mutations. The most common? EGFR, ALK, ROS1, KRAS, MET, RET, NTRK. If your tumor has one of these, there’s a pill that attacks it directly.

Take osimertinib. Approved in 2020 for early-stage EGFR-positive lung cancer, it’s used after surgery to kill leftover cancer cells. In the ADAURA trial, it cut the risk of recurrence or death by 83%. That’s not a small improvement. That’s life-changing.

And here’s the kicker: the earlier you catch the cancer, the more likely it is to have one of these mutations. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer predicts that by 2025, 70% of early-stage lung cancers found through screening will have actionable targets. In late-stage cases? Only 30% do.

That means screening isn’t just about finding cancer. It’s about finding cancer that can be stopped before it spreads-with a daily pill, not chemo.

The Future: AI, Liquid Biopsies, and Personalized Risk

The next wave is already here. AI tools like LungQ, approved by the FDA in January 2023, help radiologists spot nodules faster and reduce false positives by 15-20%. That means fewer unnecessary biopsies and less stress for patients.

And then there’s liquid biopsy. Instead of waiting for a tumor to show up on a scan, researchers are testing blood for bits of tumor DNA-called ctDNA. If they find it, they can detect cancer months before a CT scan would show anything. Trials like NCT04541082 are testing whether adding liquid biopsy to LDCT screening can catch even more early cancers.

Soon, screening might not just be based on smoking history. The National Cancer Institute’s PACIFIC trial, launching in 2024, will test whether combining genetic risk, family history, air pollution exposure, and other factors can create a smarter, more personalized risk score. You might not need to smoke 20 pack-years to qualify. If your genetic risk is high, you might be screened starting at 45.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re a current or former smoker aged 50 or older with a 20+ pack-year history:

- Ask your doctor if you qualify for LDCT screening. Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- Confirm your screening center is ACR-accredited. You can check at acr.org.

- Ask about smoking cessation support-even if you’ve quit. It still helps.

- If you’re told you’re not eligible, ask why. Check if your insurer is using outdated rules.

- Bring a family member to your appointment. It helps to have someone remember what was said.

If you’re a provider: use your EHR to flag eligible patients. Offer a shared decision-making visit. Link screening to quit-smoking programs. This isn’t just about detecting cancer. It’s about saving lives.

What’s Next?

Lung cancer screening and targeted therapy are no longer separate stories. They’re part of the same solution. Screen early. Find the mutation. Treat precisely. That’s the new standard.

The goal isn’t just to live longer. It’s to live better-with fewer side effects, fewer hospital visits, and more control. By 2030, survival rates could climb from 23% to over 40%. That’s not a guess. It’s the projection from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

It’s not perfect. The system is still uneven. Access is still unequal. But the tools are here. The science is clear. The question isn’t whether we can do better. It’s whether we will.

Who qualifies for lung cancer screening in 2026?

As of 2026, you qualify for annual low-dose CT (LDCT) screening if you’re between 50 and 80 years old, have a 20+ pack-year smoking history, and currently smoke or quit within the last 30 years. The American Cancer Society’s 2023 guidelines removed the 15-year quit limit, meaning former smokers remain eligible even decades after quitting. Medicare covers screening for those aged 50-77 with a 20-pack-year history.

Is LDCT screening safe? What about radiation?

Yes, LDCT is safe. It uses 70-80% less radiation than a standard diagnostic CT scan-about the same as a mammogram. The radiation dose is low enough that the benefits of early cancer detection far outweigh the risks, even for people getting screened yearly. There’s no evidence that annual LDCT causes cancer. The real risk is missing a tumor because you didn’t get screened.

What if my LDCT scan shows a nodule?

Most nodules (over 95%) are not cancer. If one is found, you’ll likely get a follow-up scan in 3-6 months to see if it grows. If it does, your doctor may order a biopsy or refer you to a lung specialist. Only about 3-4% of screened people end up needing a biopsy. The key is using an accredited center with protocols for tracking nodules over time.

Can targeted therapy cure early-stage lung cancer?

Targeted therapy doesn’t always cure early-stage lung cancer, but it dramatically reduces the chance of it coming back. For example, osimertinib, used after surgery for EGFR-positive tumors, reduces recurrence risk by 83% over five years. Many patients stay cancer-free for years with just daily pills. It’s not a magic bullet, but it’s one of the biggest advances in lung cancer treatment in decades.

Why aren’t more people getting screened if it saves lives?

Four main reasons: many doctors don’t know the updated guidelines, patients aren’t aware they’re eligible, screening centers are hard to find (especially in rural areas), and insurance rules vary. Only about 18% of eligible people are screened. Fixing this requires better provider education, patient outreach, and expanding access to accredited facilities.

Do I still need to quit smoking if I’m getting screened?

Absolutely. Screening doesn’t protect you from future cancer. Quitting smoking reduces your risk of new tumors, heart disease, COPD, and other cancers. In fact, screening programs that offer quit-smoking support see higher participation and better long-term outcomes. Even if you’ve smoked for decades, quitting at any age helps.