Why Generic Switching Raises Concerns for NTI Drugs

What Makes a Drug a Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) Drug?

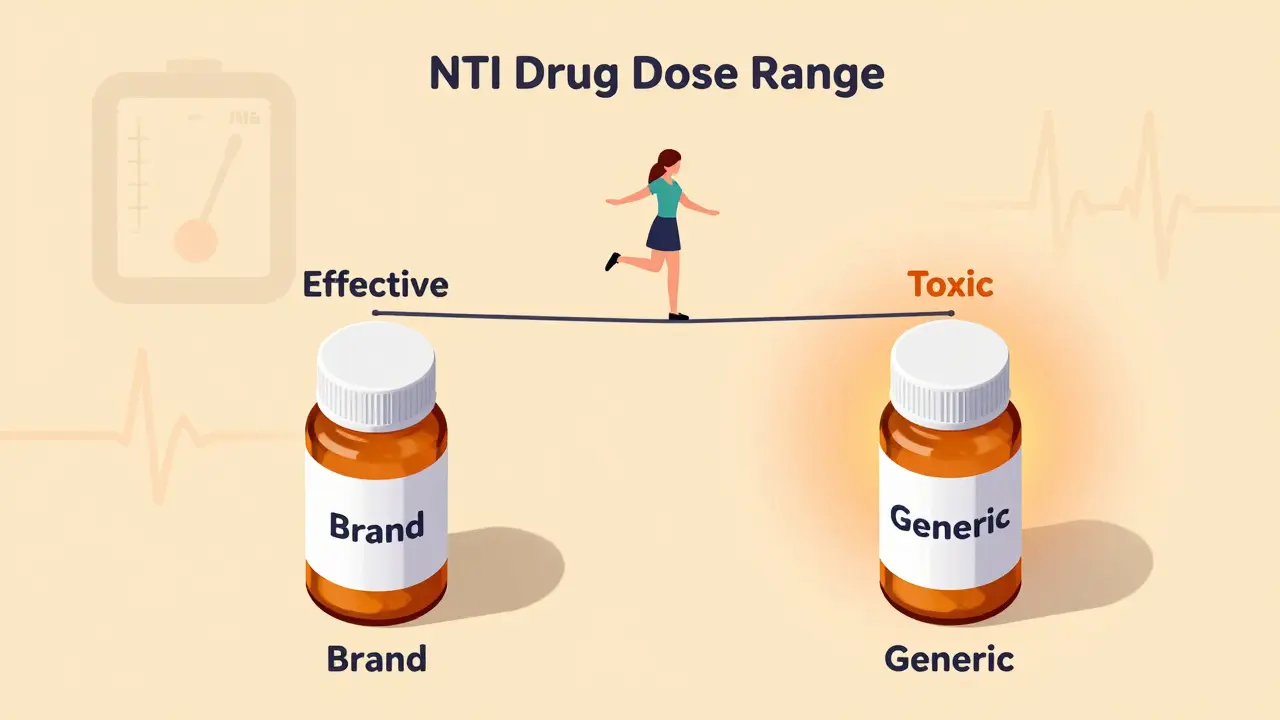

A narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug is one where the difference between a safe, effective dose and a dangerous, toxic dose is tiny. Think of it like walking a tightrope - one step too far, and you fall. For these drugs, the amount that helps you is almost the same as the amount that can hurt you. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines them as medications where small differences in dose or blood concentration can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure.

Take warfarin, for example. It’s used to prevent blood clots. The goal is to keep your INR (a blood test that measures clotting time) between 2.0 and 3.0. If it drops below 2.0, you’re at risk of a stroke. If it climbs above 3.0, you could bleed internally - even from a minor bump. That’s a range of just 1.0 point. Now imagine switching from one brand of warfarin to a generic version. Even a 10% change in how your body absorbs the drug could push you out of that safe zone.

Other common NTI drugs include phenytoin (for seizures), lithium (for bipolar disorder), digoxin (for heart rhythm), and methadone (for pain or addiction treatment). Phenytoin’s safe range is 10 to 20 micrograms per milliliter of blood. Go above 20, and you might start experiencing dizziness, slurred speech, or even loss of coordination. Go below 10, and seizures could return. There’s no room for error.

Why Generic Substitution Is Risky for NTI Drugs

The FDA allows generic drugs to be considered bioequivalent if their absorption in the body is within 80% to 125% of the brand-name version. That sounds fine - until you realize that for an NTI drug, a 25% increase in absorption could push you into toxic territory. A 20% drop could mean the drug stops working.

Here’s how it plays out in real life. A patient on brand-name Coumadin (warfarin) has stable INR levels. They switch to a generic version, and their doctor doesn’t change the dose. A week later, their INR spikes to 5.0. They end up in the hospital with internal bleeding. Or, conversely, their INR drops to 1.5. They develop a blood clot. Both scenarios have happened.

It’s not just about the active ingredient. Generic versions can use different fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes. These changes don’t matter for most drugs. But for NTI drugs, even minor differences in how the tablet breaks down in your stomach can affect how much of the drug enters your bloodstream. One study found that switching from brand to generic phenytoin led to breakthrough seizures in patients who had been seizure-free for years.

What the Experts Say - And Why They Disagree

The FDA insists that approved generic NTI drugs are safe and interchangeable. They point to data showing that, on average, generics perform just as well. But doctors and pharmacists who work with these drugs daily see a different picture.

The American Medical Association (AMA) doesn’t take sides. Instead, they say the decision should be up to the prescribing doctor. That’s because every patient is different. One person might absorb a generic version perfectly. Another might have a reaction that no lab test can predict.

Some pharmacists, especially those in smaller, independent pharmacies, express doubt. A 2019 survey found that while most pharmacists trusted generic NTI drugs, a significant number - particularly women and those outside large chains - were skeptical. Why? Because they’ve seen the consequences. They’ve had patients come in with new symptoms after a switch. They’ve had to adjust doses after a pharmacy substitution they didn’t authorize.

There’s even stronger language from some experts: “Generic substitution is not applicable for drugs with narrow therapeutic index.” That’s not hyperbole. It’s a direct response to decades of documented cases where switching caused harm.

Real Cases: When a Switch Went Wrong

In the 1980s, a wave of reports came in from hospitals: patients on phenytoin were suddenly having seizures after their pharmacy switched them to a generic version. Blood tests showed their drug levels had dropped - not because they missed a dose, but because the generic version didn’t absorb the same way.

Another case involved a man on long-term methadone for pain. He’d been stable for five years. His insurance switched him to a cheaper generic. Within days, he started feeling dizzy and nauseated. His breathing slowed. He was rushed to the ER. His blood level of methadone had spiked - the generic version had higher bioavailability. He survived, but only because his wife noticed the change and insisted on a blood test.

Warfarin is the most studied. One 2007 study claimed generic warfarin was safe to substitute. But other studies contradicted it. In one, patients who switched from Coumadin to generic warfarin - with no other changes - saw their INR fluctuate by up to 30%. That’s not a minor variation. That’s a clinical emergency waiting to happen.

What Patients Need to Know

If you’re on an NTI drug, you’re not just taking a pill. You’re managing a delicate balance. You need to be your own advocate.

- Don’t assume generics are interchangeable. Just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s identical in how your body handles it.

- Ask your doctor before any switch. Even if your pharmacist says it’s fine, get written approval from your prescriber.

- Keep a medication log. Write down the name of the drug, the manufacturer, and the dose. Take this list to every appointment.

- Know your numbers. If you’re on warfarin, know your last INR. If you’re on lithium, know your last blood level. Track changes.

- Report any new symptoms immediately. Dizziness, confusion, unusual bleeding, seizures, or extreme fatigue could mean your drug level is off.

Some patients are told, “It’s just a generic - it’s the same thing.” But for NTI drugs, that’s not true. It’s like swapping out one brand of brake pads for another. They might look the same, but if they don’t grip the same way, you’re risking your life.

What Needs to Change

The current system was built for cost savings, not patient safety. The FDA’s 80-125% bioequivalence standard was never designed for NTI drugs. Yet it’s still used.

Some states, like North Carolina, have laws that restrict automatic substitution for NTI drugs. Pharmacists must get explicit permission from the prescriber before switching. That’s a step in the right direction.

What’s needed is a two-tier system: one set of rules for most drugs, and stricter ones for NTI drugs. That could mean tighter bioequivalence limits - say, 90-111% instead of 80-125%. Or mandatory therapeutic drug monitoring after any switch. Or requiring pharmacies to stock the brand-name version if the patient requests it.

Until then, the burden falls on patients and doctors. And that’s unfair. NTI drugs aren’t rare - they’re used by millions. Warfarin alone is prescribed to over 1 million people in the U.S. each year. We can’t keep treating them like ordinary pills.

Comments (14)

Akhona Myeki

3 Feb 2026

The FDA's 80-125% bioequivalence standard is a joke for NTI drugs. I've seen patients on warfarin crash after generic switches-internal bleeding, ER visits, the whole nightmare. This isn't theoretical. It's systemic negligence dressed up as cost-cutting. If you're okay with people dying because a pill looks cheaper, then you're not saving money-you're just outsourcing morality.

Chinmoy Kumar

4 Feb 2026

i never knew how delicate these drugs are 😅 like, i thought generics were just cheaper versions of the same thing… but wow. this post opened my eyes. even small changes in fillers can mess with someone’s brain or heart? that’s wild. maybe we need a special label for ntis-like ‘handle with care’ or something. thanks for sharing this.

Brett MacDonald

6 Feb 2026

so like… if the body absorbs 125% of the drug… is that just… more drug? or is it like, the drug is trying to escape and your liver is like ‘hold up bro’?

Sandeep Kumar

6 Feb 2026

western medicine is broken. india makes 80% of the world’s generics and we dont have these problems. why? because we dont let bureaucrats decide what’s safe. doctors know. patients know. stop pretending a lab test in a lab coat is smarter than a man who’s been giving pills for 30 years

Gary Mitts

7 Feb 2026

So you’re telling me the same pill, made by a different company, might kill you?

Yep. That’s capitalism.

clarissa sulio

8 Feb 2026

My dad was on digoxin for 12 years. Brand only. His cardiologist refused to switch. Said if it ain’t broke, don’t touch it. He’s 84 and still hiking. I think he’s onto something.

Anthony Massirman

8 Feb 2026

NTI drugs are the reason we need better drug regulation. Not more bureaucracy. Better science. The 80-125% rule was made for aspirin, not lithium. Fix the standard or ban auto-substitution. Either way, stop pretending this is fine.

Solomon Ahonsi

9 Feb 2026

Why do we even bother with generics if they’re this dangerous? Just make everyone pay for brand name. Problem solved. Also, I’m tired of hearing about warfarin. Everyone’s on warfarin. What about phenytoin? Anyone care about phenytoin?

George Firican

11 Feb 2026

There’s a deeper philosophical tension here: the illusion of equivalence. We treat pharmaceuticals as if they’re interchangeable commodities, like two bags of rice from different brands. But biology isn’t a spreadsheet. The human body doesn’t care about FDA percentages-it cares about rhythm, balance, homeostasis. A 10% fluctuation in absorption isn’t a statistical outlier-it’s a seismic shift in a fragile ecosystem. We’ve outsourced trust to regulators and manufacturers, but the body remembers. It remembers the exact milligram that kept the seizure at bay. It remembers the subtle shift that triggered the bleed. We’ve reduced life to a cost-benefit analysis. And now we’re surprised when life breaks.

Matt W

13 Feb 2026

My aunt switched to generic lithium and started crying for no reason for three weeks. She thought she was depressed again. Turned out her blood levels were off. She’s fine now, but man… I didn’t even know this was a thing. Thanks for the heads up. I’m printing this out for my grandma’s pharmacist.

Bridget Molokomme

13 Feb 2026

Oh so now we’re blaming generics? Funny how the same people who scream about drug prices are now terrified of the cheap version. Maybe if you didn’t get your meds from a pharmacy that outsources to Bangladesh, you wouldn’t have this problem?

Vatsal Srivastava

14 Feb 2026

NTI drugs are a myth created by Big Pharma to keep people buying expensive brands. The FDA data is clear. The studies are replicated. Your anecdote about your cousin’s neighbor’s dog is not evidence. Stop fearmongering

Brittany Marioni

14 Feb 2026

This is so important. Please, everyone-write to your state legislators. Ask them to support bills that require prescriber consent before switching NTI drugs. And if you’re on one of these meds, keep a medication log. Write down the manufacturer. Take a photo of the pill. Save your receipts. You’re not being paranoid-you’re being proactive. Your life depends on it.

Monica Slypig

15 Feb 2026

Typo in the FDA definition? 80-125%? That’s not a range, that’s a death sentence. And the fact that people still believe generics are ‘just as good’ shows how brainwashed we are by corporate propaganda. I’m not switching my warfarin. Ever. And if my pharmacist tries? I’m taking my business to the next town.