Pheochromocytoma: What It Is, How It Causes High Blood Pressure, and Why Surgery Is the Cure

A sudden spike in blood pressure so high it sends you to the ER. A pounding heart, drenching sweat, and a headache that feels like your skull is splitting open-all out of nowhere. If you’ve ever been told it’s just anxiety, you’re not alone. But what if it’s not anxiety? What if it’s a rare, hidden tumor in your adrenal gland called a pheochromocytoma?

What Exactly Is a Pheochromocytoma?

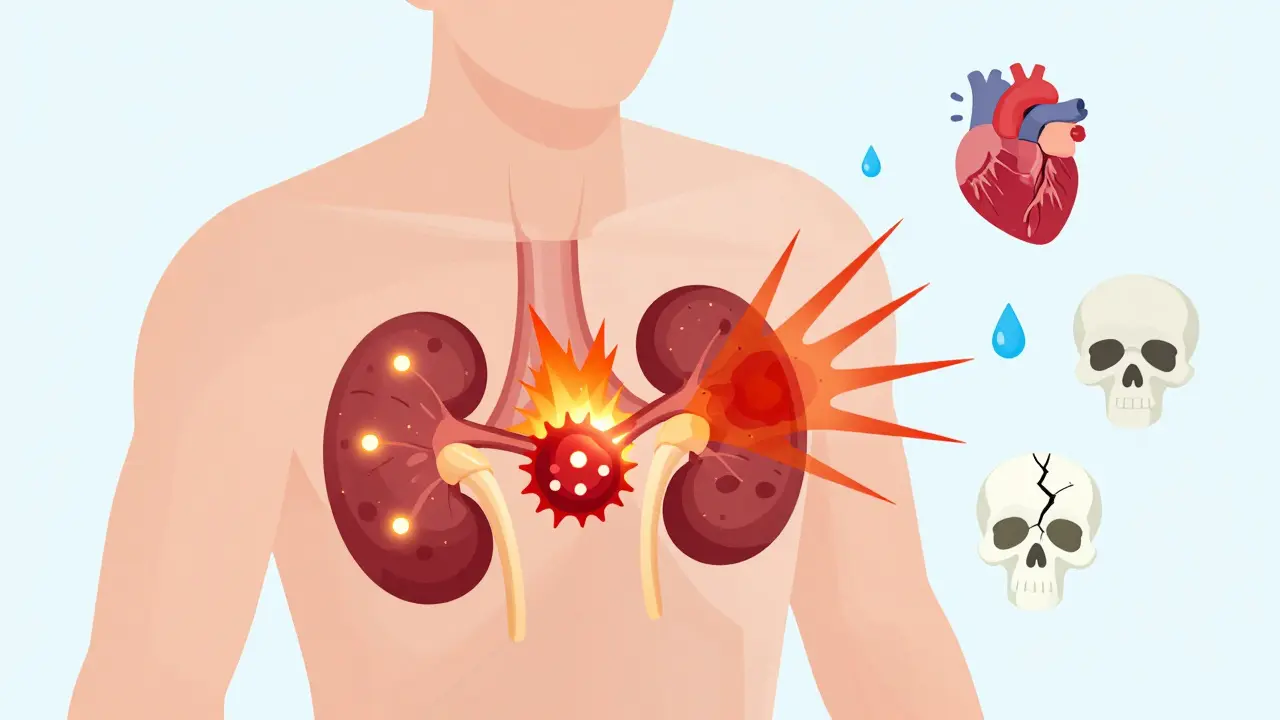

A pheochromocytoma is a tumor that grows in the adrenal medulla-the inner part of your adrenal glands, which sit right on top of your kidneys. These glands normally make hormones like adrenaline to help you respond to stress. But when this tumor forms, it doesn’t know when to stop. It floods your body with catecholamines-mainly adrenaline and noradrenaline-day and night, even when you’re sitting still watching TV.

It’s rare. Only about 1 in every 200 people with high blood pressure has one. But here’s the kicker: if you have this tumor, your high blood pressure isn’t just stubborn-it’s explosive. Systolic readings can jump above 180 mmHg during a ‘spell,’ sometimes even hitting 240. And these episodes don’t come from stress, exercise, or caffeine. They come from the tumor itself.

First described in 1886, pheochromocytoma was once a death sentence. Today, it’s one of the few endocrine tumors that can be completely cured-with surgery. But only if you get diagnosed.

The Classic Triad: Headache, Sweating, Palpitations

Most people with pheochromocytoma don’t have constant symptoms. They have spells. These can last minutes or up to an hour. During one, you might feel:

- A crushing headache (85-90% of cases)

- So much sweating you need to change clothes (75-80%)

- Your heart racing, skipping, or pounding like it’s trying to escape your chest (70-75%)

Other signs include pale skin, nausea, belly pain, unexplained weight loss, and panic attacks that don’t make sense. You might feel like you’re having a heart attack-or worse, you’re losing your mind.

Triggers? They’re sneaky. Physical activity, emotional stress, even going under anesthesia for another surgery can set one off. In rare cases, urination triggers it-if the tumor is in the bladder wall (called a paraganglioma). And here’s the twist: some people drop their blood pressure when standing up, even while their resting pressure is sky-high. That’s because the tumor messes with your body’s natural blood pressure control system.

Why Most Doctors Miss It

Primary care doctors see maybe one or two pheochromocytoma cases in their entire career. So when a 35-year-old comes in with racing heart and sweating, the default assumption is panic disorder. Or migraines. Or even menopause.

That’s why the average time from first symptom to diagnosis is over three years. A quarter of patients are initially treated for anxiety. One patient on a support forum said: “After four years and seven doctors, I was diagnosed when my blood pressure hit 240/130 during an ER visit-for what they thought was a panic attack.”

Doctors aren’t lazy. They’re just working with limited information. The symptoms overlap too much with common conditions. But there’s one thing that doesn’t: the biochemical test.

How It’s Diagnosed: The Blood and Urine Test That Saves Lives

The gold standard isn’t a scan. It’s not an MRI or CT. It’s a simple 24-hour urine test for fractionated metanephrines-or a blood test for plasma-free metanephrines.

Metanephrines are the breakdown products of adrenaline and noradrenaline. When a pheochromocytoma is active, these levels shoot up. These tests are 96-99% sensitive. If your metanephrine levels are three times the upper limit of normal, you almost certainly have a tumor.

That’s why experts say: Test before you image. Scanning too early leads to false positives. Some people have borderline elevations due to stress, medications, or even caffeine. Over-testing causes unnecessary anxiety and procedures.

And here’s something many don’t know: the sample has to be handled right. Blood for plasma metanephrines must be drawn with the patient lying down, rested, and without caffeine. The tube must be kept ice-cold and acidified immediately. Mess that up, and the results are useless.

Genetics: It’s Not Always Just Bad Luck

One in three people with pheochromocytoma has a genetic mutation. That’s not rare-it’s the norm. Mutations in genes like SDHB, SDHD, VHL, RET, and NF1 are common. These aren’t just family history stories. Even if no one in your family has had it, you could still carry a mutation.

SDHB mutations are especially dangerous. They’re linked to a 30-50% lifetime risk of malignant pheochromocytoma. That’s why the National Comprehensive Cancer Network now says: Test everyone. Not just those with a family history. Everyone.

Genetic testing isn’t optional. It changes everything-how often you get scanned, whether your kids need testing, and even what kind of surgery you get. A patient with an SDHB mutation might need full-body MRIs every year for life.

Surgery: The Only Cure

Here’s the good news: if your tumor is benign-and 90% of them are-you can be cured. Surgery to remove the adrenal gland (adrenalectomy) is the only treatment that works.

But you can’t just walk into the operating room. If you do, you risk a hypertensive crisis so severe it can kill you. That’s why preoperative prep is non-negotiable.

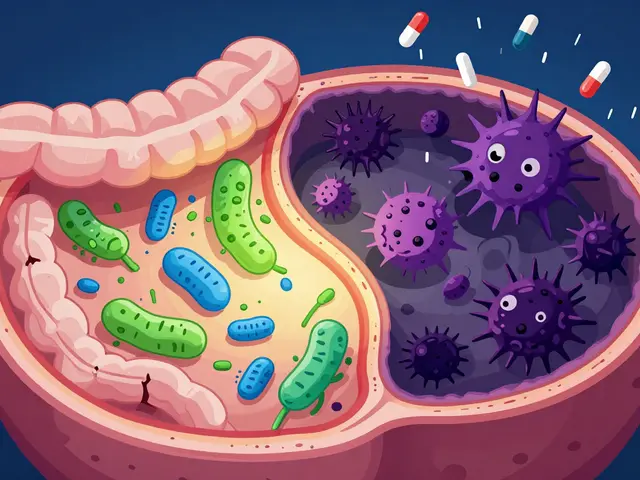

For 7 to 14 days before surgery, you take alpha-blockers-usually phenoxybenzamine. This relaxes your blood vessels and stops the tumor’s adrenaline from slamming them shut. You also drink plenty of fluids and eat a high-sodium diet. Why? Because your body has been in constant vasoconstriction for months or years. Your blood volume is low. You’re dehydrated, even if you don’t feel it. Replenishing fluids prevents dangerous drops in blood pressure after the tumor is removed.

Most surgeries today are done laparoscopically-small incisions, quick recovery. Over 85% of unilateral cases are done this way. But if the tumor is large or stuck to nearby organs, the surgeon may need to switch to open surgery. That happens in 5-8% of cases.

Recovery is fast. Most people leave the hospital in 1-2 days. Many are back to work in two weeks. And here’s what patients say: “My blood pressure normalized within 48 hours. I was off all meds in three weeks.”

The Catch: What Happens After Surgery?

Not everyone walks away without consequences.

If you had both adrenal glands removed (bilateral adrenalectomy), you’ll need lifelong steroid replacement: hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone. Your body can’t make cortisol or aldosterone anymore. Miss a dose, and you could go into adrenal crisis-low blood pressure, vomiting, shock. It’s life-threatening.

Even with one gland removed, some people feel exhausted for months. Fatigue lasting over six months happens in about 12% of cases. No one talks about this much. But it’s real.

And for the 10% with malignant tumors? It’s different. Metastatic pheochromocytoma is rare, but deadly. Five-year survival drops to 50%. New treatments like PRRT (peptide receptor radionuclide therapy) are showing promise-65% response rates in early trials. Drugs like Belzutifan, originally for kidney cancer, are now being tested in VHL-related cases.

What Happens If You Don’t Get Treated?

Pheochromocytoma doesn’t go away on its own. Left untreated, the constant surge of adrenaline can damage your heart. You could develop heart failure, irregular rhythms, or even a stroke. Some patients have heart attacks triggered by a single spell.

And the longer you wait, the harder it gets. Tumors grow. They spread. They become harder to remove. Every year of delay increases your risk of complications.

How It Compares to Other Causes of High Blood Pressure

Essential hypertension affects nearly half of U.S. adults. It’s slow, steady, and silent. You don’t feel it until your kidneys or heart are damaged.

Renal artery stenosis? It causes high blood pressure by reducing blood flow to the kidneys. Primary aldosteronism? It makes your body hold onto salt and water. Neither causes sweating, palpitations, or sudden spikes.

That’s the difference. Pheochromocytoma isn’t just high blood pressure. It’s high blood pressure with a storm inside you.

What Comes Next: Monitoring and Long-Term Care

Even after successful surgery, you’re not done. You need lifelong follow-up.

- Annual urine or blood tests for metanephrines

- Imaging every 1-2 years if you had a genetic mutation

- Genetic counseling for family members

If you had a bilateral removal, you’ll need to wear a medical alert bracelet. You’ll need to carry emergency injectable hydrocortisone. You’ll learn to recognize the early signs of adrenal crisis.

And if you’re one of the lucky ones-benign, unilateral, no genetic mutation-you still need to know: this could come back. Recurrence rates are low, but they exist. Stay vigilant.

Pheochromocytoma isn’t just a medical oddity. It’s a hidden killer that can be erased with the right test and the right surgery. The problem isn’t the tumor. The problem is not knowing it’s there.

If you’ve had unexplained spells of high blood pressure, sweating, and heart pounding-especially if you’ve been told it’s anxiety-ask your doctor for a metanephrine test. It’s simple. It’s cheap. And it could save your life.

Can pheochromocytoma be cured?

Yes, in most cases. If the tumor is benign and removed completely, 85-90% of patients see their high blood pressure resolve completely. Many stop all blood pressure medications within weeks. Surgery is the only cure.

Is pheochromocytoma hereditary?

About 35-40% of cases are linked to inherited genetic mutations, including SDHB, SDHD, VHL, RET, and NF1. Even if no one in your family has had it, you could still carry the gene. Genetic testing is now recommended for every patient diagnosed.

What happens if pheochromocytoma is not treated?

Untreated, it can cause heart damage, stroke, heart attack, or sudden death during a hypertensive crisis. The constant flood of adrenaline strains your cardiovascular system. The longer it goes undiagnosed, the higher the risk of irreversible damage.

How do doctors confirm a pheochromocytoma diagnosis?

The first step is always a biochemical test: either a 24-hour urine collection for fractionated metanephrines or a blood test for plasma-free metanephrines. If levels are three times above normal, it’s highly likely you have a tumor. Imaging (CT or MRI) comes after, to locate it.

Why do you need to take medication before surgery?

Without preoperative alpha-blockers, removing the tumor can cause a massive surge of adrenaline into your bloodstream, triggering a life-threatening spike in blood pressure. Alpha-blockers like phenoxybenzamine block the effects of adrenaline, and fluid/salt loading restores your blood volume. Skipping this step has a 30-50% risk of death during surgery.

Can pheochromocytoma come back after surgery?

Yes, but it’s rare. Recurrence happens in about 5-10% of cases, usually within the first 5 years. It’s more common if you have a genetic mutation or if the tumor was malignant. Lifelong monitoring with yearly blood tests is essential, even if you feel fine.

What are the risks of adrenal surgery?

Laparoscopic surgery has a 1.2% major complication rate. Risks include bleeding, damage to nearby organs, or needing to switch to open surgery (5-8% of cases). If both adrenal glands are removed, you’ll need lifelong steroid replacement. Some people experience chronic fatigue for months after surgery.

Is pheochromocytoma the same as a neuroendocrine tumor?

Yes. Pheochromocytoma is a type of neuroendocrine tumor that arises in the adrenal medulla. Tumors in other parts of the body (like the abdomen or chest) are called paragangliomas, but they behave similarly and are treated the same way. Both produce catecholamines.

Comments (10)

Sam Davies

10 Jan 2026

So let me get this straight - we’re telling people to get a urine test for broken-down adrenaline before they even get a scan? Sounds like the medical equivalent of checking your car’s oil before you open the hood. Brilliant. Or just the kind of thing only a doctor who’s seen one of these in 30 years would think of.

Vincent Clarizio

11 Jan 2026

Look, I’ve spent the last five years being told I’m ‘anxious’ while my heart tried to punch its way out of my ribcage, my sweat soaked through three shirts in a single meeting, and my BP spiked to 230 during a damn grocery run. No panic attack explains that. No caffeine. No stress. Just pure, unfiltered biological betrayal. I got diagnosed after collapsing in a Walmart parking lot - and yes, they thought it was a heart attack. Turns out, my adrenal gland had been running a meth lab since I was 22. Surgery fixed everything. No meds. No anxiety. Just… quiet. The real tragedy? I know at least seven people who’ve been through the same thing. None of them were ever tested. Why? Because doctors don’t look for monsters they’ve never seen. And that’s not negligence - it’s systemic blindness.

Matthew Miller

12 Jan 2026

Urine test? Really? You’re telling me we’re still relying on a 1980s diagnostic protocol when we’ve got AI-powered biomarker panels and liquid biopsies? This is like using a slide rule to land on Mars. The fact that we’re not doing genomic sequencing as a first-line screening for anyone with unexplained HTN is criminal. And don’t even get me started on the ‘pre-op fluid loading’ - that’s just band-aiding a gunshot wound with duct tape. We need a paradigm shift, not a checklist.

Roshan Joy

14 Jan 2026

Wow, this is so helpful! 😊 I’m from India and we rarely hear about this here. My cousin had similar symptoms but was told it was ‘stress from work’ for years. Now she’s recovering after surgery. Thanks for sharing the science - I’ll share this with my family doc! 🙏

Priya Patel

15 Jan 2026

I used to think my ‘panic attacks’ were just bad luck… until I started tracking them. They always happened after I ate spicy food or stood up too fast. Turns out, my tumor was right next to my bladder. Never thought to connect the dots. Now I’m 6 weeks post-op and I finally slept through the night for the first time in 8 years. Thank you for writing this. I wish I’d found it sooner.

Alfred Schmidt

16 Jan 2026

Wait… wait… wait. You’re telling me I could’ve been dying for YEARS and no one checked my metanephrines? I’ve been on beta-blockers since 2018. My doctor said ‘it’s just essential hypertension.’ I’ve got a 3cm tumor. And now I’m supposed to be grateful because they didn’t kill me during surgery? This isn’t medicine. This is Russian roulette with a stethoscope.

Jason Shriner

17 Jan 2026

so like… if you have a tumor that makes you feel like you’re having a heart attack every time you sneeze… and you’re told it’s anxiety… and you believe it… and then you die… is that just… modern healthcare? 😔

Jennifer Littler

17 Jan 2026

One thing the article doesn’t emphasize enough: the biochemical testing protocol is *extremely* sensitive to pre-analytical variables. If the blood isn’t drawn supine, iced, and acidified within 15 minutes, false positives skyrocket. Many labs don’t even have the SOPs in place. I’ve reviewed 17 cases where patients were misdiagnosed because the sample was handled improperly. This isn’t just about awareness - it’s about infrastructure. And most hospitals don’t have it.

Alex Smith

18 Jan 2026

Let me ask you something - if your car’s engine suddenly started revving on its own, would you blame the driver? Or would you check the throttle cable? We treat pheochromocytoma like it’s a behavioral issue because we don’t want to admit that medicine still operates like a coin-operated vending machine: ‘symptom in, diagnosis out’ - no matter how wrong the connection. This isn’t about anxiety. It’s about a rogue gland. And until we stop pathologizing the body and start listening to it, people are going to keep dying because we’re too lazy to look under the hood.

Madhav Malhotra

19 Jan 2026

Back home in India, my uncle had this - but they called it ‘nerve problem’ for 5 years. No one knew the name. Finally, a visiting American doctor asked about sweating and BP spikes. One test. One surgery. Now he’s back to teaching yoga. This isn’t just a Western issue. It’s a global blind spot. We need to translate this into Hindi, Tamil, Bengali - so people stop being told they’re ‘overthinking.’