QT Prolongation and Sudden Cardiac Death from Medications: Key Risk Factors to Know

QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Risk Assessment Tool

Based on the article "QT Prolongation and Sudden Cardiac Death from Medications: Key Risk Factors to Know"

Every year, hundreds of people die suddenly from a heart rhythm gone wrong-not because of a heart attack, but because a common medication they took quietly stretched their heart’s electrical cycle beyond safe limits. This isn’t rare. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable-if you know what to look for.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

Your heart beats because of electrical signals. The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes the lower chambers of your heart (ventricles) to recharge after each beat. When that interval gets too long, the heart can’t reset properly. That’s QT prolongation. It doesn’t cause symptoms on its own. But it creates the perfect setup for Torsades de Pointes-a wild, chaotic rhythm that can turn into sudden cardiac death within seconds. The standard cutoff? A corrected QT interval (QTc) over 450 milliseconds in men, or 470 in women. But danger spikes when QTc hits 500 ms or more, or when it jumps more than 60 ms from your baseline. That’s not just a number on a screen. It’s a red flag.Medications That Can Trigger This

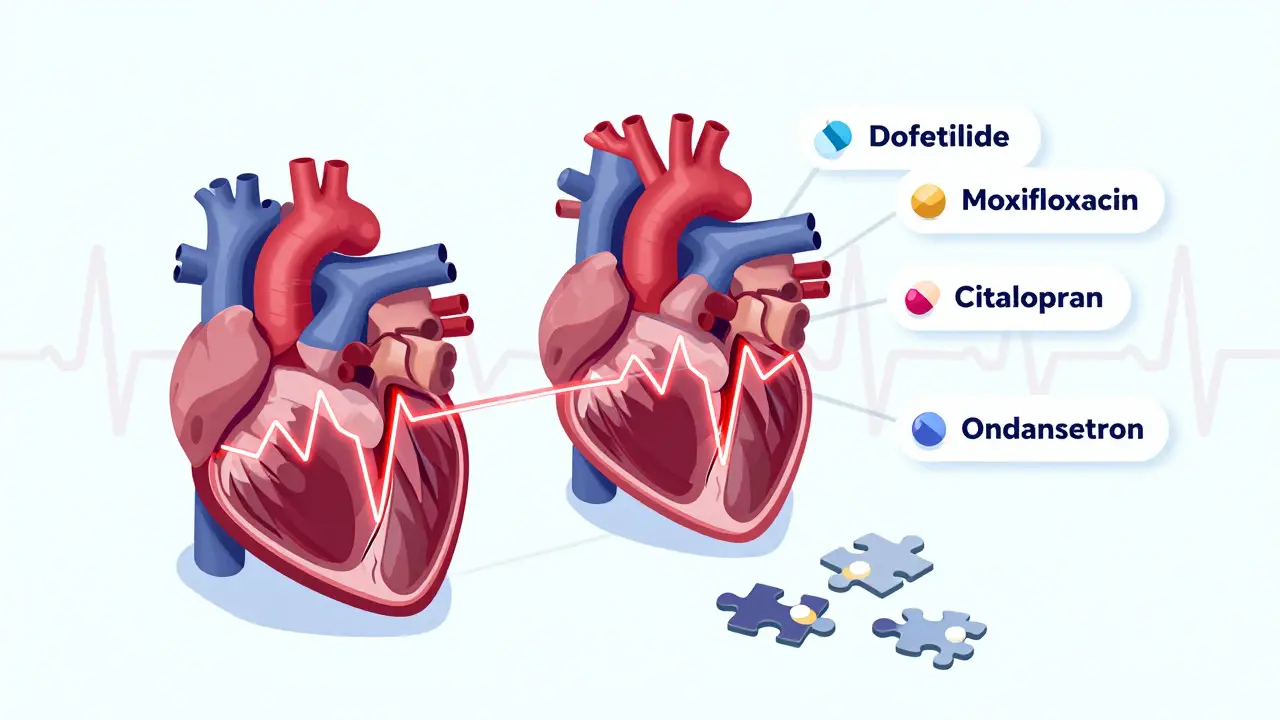

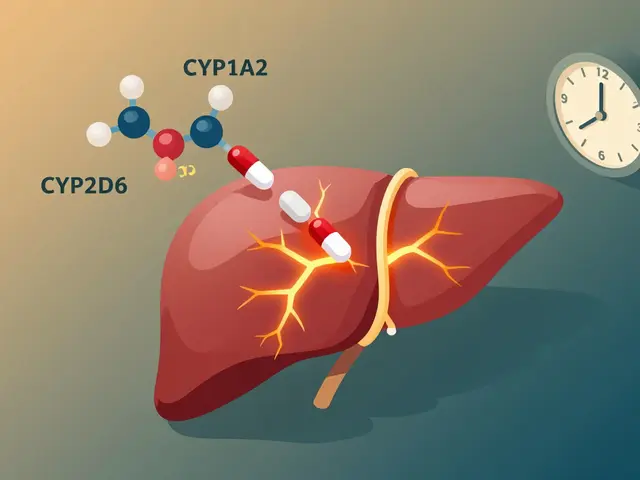

Over 100 prescription drugs can prolong the QT interval. Not all are dangerous for everyone-but some carry high risk, especially when combined. Class III antiarrhythmics like dofetilide and sotalol are the most notorious. Dofetilide alone causes Torsades de Pointes in about 3.3% of patients, even when used correctly. These drugs are meant to fix heart rhythms, but they can also create them. Antibiotics vary widely. Moxifloxacin can stretch QTc by 6-15 milliseconds. Ciprofloxacin? Barely 0-5. That’s a huge difference. Erythromycin is especially risky-especially when taken with drugs that block the CYP3A4 enzyme, like grapefruit juice, clarithromycin, or even some antidepressants. In one study, that combo raised sudden death risk fivefold. Antidepressants like citalopram (at 40 mg daily) average an 8.5 ms QTc increase. Escitalopram, its cousin, only adds 4.2 ms. The difference? A safer choice for patients with heart risks. Antipsychotics like haloperidol and ziprasidone are also on the list. So are some anti-nausea drugs like ondansetron. Even though they’re common, they’re not harmless.Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it.- Women are more susceptible than men, even at the same dose.

- Older adults take an average of 7.8 medications. About 34% of those over 65 are on at least one QT-prolonging drug. Polypharmacy is the silent killer here.

- People with heart disease face 10 to 100 times higher risk. Structural damage-like scar tissue from a past heart attack-makes the heart far more likely to tip into dangerous rhythms.

- Low potassium or magnesium is a major trigger. Correcting potassium to above 4.0 mEq/L cuts risk by 62%.

- Slow heart rate (bradycardia) makes QT prolongation worse. Some drugs, like sotalol, actually get more dangerous when the heart slows down-a quirk called reverse use dependence.

- Drug interactions are the biggest hidden danger. A drug that’s safe alone can become deadly when paired with another that blocks its metabolism. CYP3A4 inhibitors are the most common culprits.

Why ECGs Don’t Always Help

Many doctors order ECGs before prescribing QT-prolonging drugs. But here’s the problem: automated ECG machines are wrong up to 40 milliseconds off from manual readings. And even perfect measurements miss something critical: spatial dispersion of repolarization. That’s when different parts of the heart recharge at different speeds. It’s invisible on a standard 12-lead ECG. But it’s what turns a long QT into a fatal rhythm. Plus, most QTc alerts in hospitals are false positives. One study found 78% of alerts were unnecessary. That leads to alarm fatigue-clinicians start ignoring them. And that’s when someone slips through the cracks.What Actually Works to Prevent Death

The best defense isn’t more testing. It’s smarter prescribing. The MHRA recommends a simple 3-step check before giving any drug that can prolong QT:- Check baseline QTc. If it’s already over 450 (men) or 470 (women), avoid high-risk drugs.

- Fix what you can. Correct low potassium, low magnesium, and slow heart rate first. Don’t just push the drug.

- Check for interactions. Use tools like AZCERT.org or the FDA’s database. Avoid combining QT-prolonging drugs with CYP3A4 inhibitors. If you must, reduce the dose.

The Bigger Problem: Overreaction and Underestimation

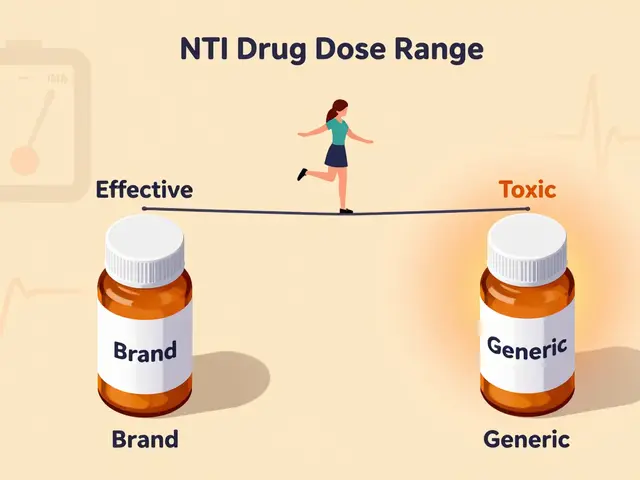

Here’s the paradox: some doctors stop safe medications because of a slightly long QTc. The European Heart Rhythm Association warns that 15-20% of heart failure patients have been taken off useful drugs-like beta-blockers-just because of QT concerns. That’s dangerous too. Stopping a life-saving drug can kill faster than a prolonged QT. Meanwhile, others ignore the risk entirely. The POST SCD study found that 78% of people who died suddenly while on QT-prolonging drugs had no arrhythmia found at autopsy. That means something else-like a heart attack or stroke-was the real cause. So not every QT prolongation leads to death. But when it does, it’s often because risk factors were ignored.

New Tools Are Changing the Game

The FDA’s CiPA initiative (launched in 2013) replaced old, flawed tests with modern models that simulate how drugs affect the whole heart-not just one ion channel. It’s 40% more accurate. And now, 92% of big pharma companies use it. In 2023, the FDA approved the first AI-based QT monitoring system, QTguard by Verily. It cuts false alarms by 53% by learning what real danger looks like in ECG waveforms-not just the QTc number. The International Council for Harmonisation now requires new drugs to be tested for T-wave shape changes, not just QT length. That’s a big step forward. Because the T-wave peak-to-end interval is actually the strongest predictor of sudden death. Each 1-standard-deviation increase raises risk by 21%.What You Can Do Now

If you’re a patient:- Ask your doctor: “Is this drug known to affect heart rhythm?”

- Know your electrolytes. Get blood work if you’re on long-term meds.

- Don’t take grapefruit juice with antibiotics or antifungals unless your doctor says it’s safe.

- If you feel dizzy, have palpitations, or pass out after starting a new drug-get help immediately.

- Use AZCERT.org or the FDA’s QT drug list before prescribing.

- Don’t order ECGs for low-risk drugs like ondansetron unless there’s another reason.

- Correct potassium and magnesium before giving high-risk meds.

- Check for drug interactions-especially CYP3A4 inhibitors.

- Remember: QT prolongation isn’t the disease. It’s a warning sign. The real danger is what happens when it’s ignored.

Final Thought

QT prolongation isn’t a bug. It’s a feature of how some drugs interact with the heart. The problem isn’t the medicine. It’s the lack of attention to context: the patient’s age, their other drugs, their electrolytes, their heart health. We’ve moved past the days when a long QTc meant automatic drug withdrawal. We’re now in the era of precision risk assessment. The tools are here. The science is clear. What’s missing is consistent application. Don’t wait for someone to die before you ask: Could this drug be the one?Can a normal ECG rule out risk for QT prolongation?

No. A normal ECG doesn’t guarantee safety. Many people with normal baseline QTc can still develop dangerous prolongation after taking a high-risk drug, especially if they have low potassium, slow heart rate, or drug interactions. The ECG is a snapshot, not a forecast.

Which antidepressants are safest for people with heart concerns?

Escitalopram and sertraline carry the lowest risk for QT prolongation among SSRIs. Citalopram at doses above 20 mg is riskier. Mirtazapine and bupropion are generally neutral. Always check the AZCERT database before prescribing, and consider baseline ECG for patients over 65 or with heart disease.

How often should QTc be checked after starting a high-risk drug?

For high-risk drugs like dofetilide or sotalol, check QTc within 2-5 days after starting or increasing the dose. For moderate-risk drugs like citalopram or moxifloxacin, check once after 1-2 weeks if there are risk factors. If no changes and no risk factors, routine monitoring isn’t needed.

Are over-the-counter drugs safe for QT prolongation?

Some OTC meds can be risky. Antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and pseudoephedrine can prolong QT, especially in high doses or with other risk factors. Herbal supplements like licorice root can lower potassium. Always review all medications-prescription, OTC, and supplements-before prescribing any new drug.

Can genetic testing predict QT prolongation risk?

Yes, but not routinely yet. Mutations in genes like KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A cause inherited long QT syndrome. These are rare, but they increase sensitivity to drugs. The NIH’s All of Us program is collecting genomic data to identify these variants. For now, genetic testing is only recommended if there’s a family history of sudden death or unexplained fainting.

Comments (13)

Winni Victor

26 Dec 2025

So let me get this straight-we’re now policing every damn pill like it’s a grenade because some algorithm says the QT interval is 471ms? My grandma takes citalopram, grapefruit juice, and a half-dozen other things like it’s candy-and she’s still out here gardening at 82. Maybe the real problem is we’ve turned medicine into a horror movie where every side effect is a jump scare.

Linda B.

27 Dec 2025

The FDA doesn't want you to know this but the entire QTc monitoring system was designed by pharmaceutical lobbyists to justify more expensive ECG machines and create liability insurance loopholes. The real cause of sudden death? Corporate greed masked as clinical caution. They profit from fear. And you? You're the product.

Christopher King

29 Dec 2025

Let me ask you this-when did medicine become a game of numbers instead of a conversation between human beings? We’ve got algorithms screaming about 500ms while ignoring the fact that half these patients are lonely, sleep-deprived, and eating processed food 24/7. The heart doesn’t just respond to ions-it responds to meaning. To love. To being seen. You can’t measure that on an ECG. But you can feel it when someone dies alone in a hospital room because no one asked if they were okay.

Michael Dillon

29 Dec 2025

Everyone’s panicking about QT prolongation like it’s a death sentence. Meanwhile, millions of people take SSRIs and antibiotics without issue. The real issue is overtesting. If you’re young, healthy, and not on five drugs at once, stop getting ECGs for everything. You’re not helping. You’re just adding noise to the system.

Gary Hartung

30 Dec 2025

It is, indeed, a profound and deeply troubling epistemological crisis in contemporary cardiology: the reduction of the human organism to a series of quantifiable, algorithmically interpreted, and clinically sanitized intervals-while simultaneously neglecting the phenomenological reality of the patient’s lived experience. The QT interval, as a metric, is not merely a measurement-it is a symbol of our collective surrender to techno-bureaucratic hegemony in medical decision-making.

Ben Harris

1 Jan 2026

My cousin died from torsades after taking ondansetron for nausea. They didn't even check her potassium. She was 29. No history. Just a migraine and a bad taco. Now I check every single med I take-even Advil-on AZCERT. I don't trust doctors anymore. I trust databases. And I tell everyone. Everyone.

Carlos Narvaez

3 Jan 2026

QTc >500ms = high risk. Baseline QTc >450/470 = avoid high-risk drugs. Potassium <4.0 = fix it first. Drug interaction? Check CYP3A4. Simple. Not complicated. Stop overthinking it.

Zabihullah Saleh

4 Jan 2026

Back in my village in Afghanistan, we used to say: 'The medicine is not the poison-the ignorance is.' I’ve seen old men take ten pills a day, eat nothing but bread and tea, and live to 95. But I’ve also seen young nurses in New York die from one new script because no one checked their magnesium. It’s not the drug. It’s the system forgetting to look at the whole person.

Sophie Stallkind

4 Jan 2026

As a clinical pharmacist with over two decades of experience, I must emphasize that the implementation of systematic pre-prescription screening protocols-particularly those incorporating electronic health record-based decision support tools such as those deployed at Mayo Clinic-has demonstrably reduced iatrogenic arrhythmic events by over one-third in institutional settings. Adherence to evidence-based guidelines, including electrolyte correction and interaction avoidance, remains paramount. We must not allow alarm fatigue to erode the foundational principles of patient safety.

Katherine Blumhardt

6 Jan 2026

so like... i just started sertraline and my friend said dont take it with grapefruit juice but i dont even know what that is like is it the juice or the fruit?? also i took a benadryl last week and now i feel weird but my dr said its fine?? i just want to live to 30??

sagar patel

7 Jan 2026

QT prolongation is not a myth. But the fear is manufactured. In India, we prescribe citalopram to elderly patients daily. No ECG. No monitoring. Fewer deaths than in the US. Why? Because we treat the person, not the number. Your system is broken-not the science.

Bailey Adkison

7 Jan 2026

You people act like QT prolongation is some new evil. It’s been known since the 80s. If you’re taking a drug that affects it, you’re either a doctor who should know better or a patient who didn’t read the damn label. Stop pretending you’re victims of a conspiracy. You’re just lazy.

Oluwatosin Ayodele

8 Jan 2026

Let me tell you something about Nigeria. We don’t have ECG machines in half the clinics. We don’t have AZCERT. We don’t have 100-dollar blood tests. But we still save lives. We look at the patient. We ask: Are they swollen? Are they weak? Do they have diarrhea? Low potassium? Then we give potassium. We don’t need AI. We need common sense. And you? You’re overcomplicating death.